-

Manuela Pellegrino, Greek Language, Italian Landscape: Griko and the Re-storying of a Linguistic Minority

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. In the Land Between the Seas

2. “The World Changed”: The Language Shift Away from Griko

3. The Reappropriation of the Past

4. From “the Land of Remorse” to ‘the Land of Resource’

5. Debating Griko: The Current Languagescape

6. “Certain Things Never Change and Those Sound Better in Griko”: Living with the Language

7. The View from Apénandi: Greece’s Gaze on Grecìa Salentina

Conclusion. Chronotopes of Re-presentation

Bibliography

Introduction

The first Griko voice I ever heard still echoes in my mind: that of my grandmother Lavretàna asking me: “Teli spirì nerò?” (Griko)―“Do you want some water?” I was very little and, after she handed me the glass and I drank my water, I recall thinking that those sounds were ‘her’ way of speaking, that it was ‘her’ language. Griko was indeed her language; it was, however, not just hers. It was also my grandfather’s and my eldest uncles’ and aunties’ language. Why was it not mine too? Would I have to wait for my hair to turn white and my clothes black to speak it, I wondered?

I grew up hearing these almost mysterious sounds being used by elderly relatives and, from time to time, by my parents too. They were a very discrete but reassuringly constant presence. My parents would usually speak Salentine (the local Italo-Romance dialect) to one another; more often than not, that was the language they used to address me too. By contrast, my eldest sister, eighteen years older, would glare at me and insist, “Parla bene!” (Italian)―“Speak well!”—by which she meant “Speak Italian.” I ended up studying and learning languages, but Griko was not among them. Since it was considered ‘a dying language’—one that belonged to the domain of the elderly—it remained inaccessible to me until I finally set myself the goal of making sense of it.

Over two decades later, ’Ndata—now a smiley lady in her nineties—became not only my best friend but also one of my teachers. My parents’ house and hers are just a few meters away from one another, and I am privileged to have learned Griko by spending so much time with her (see Figure 1). Sometimes she still finds puzzling this late interest of mine and now of others: “All these people who want to learn about Griko now and even learn it! Let them go and learn the ‘Griko’ of Greece! Now we are told we are important! Like monuments. Of what? Of ourselves by now!” And she laughs. She sings in the chorus of Zollino’s center for the elderly (she is tone deaf, but don’t tell her), which also performs for visiting Greek tourists, and ’Ndata is amused to see their astonishment when they hear her say “Tèlete glicèa?”—“Do you want some sweets?” And then she drops her guard for a moment and asks me to take her to Greece, “Just to see what all this fuss is about. I’m curious,” she adds.

Figure 1: 'Ndata and I. Credit: Daniele Coricciati

This book is about Salentine Greek—or simply Griko—a language of Greek origins transmitted orally from generation to generation in Salento, in the Apulian province of Lecce, the ‘heel’ of the boot of Italy. [1] Its pool of speakers started shrinking after the contact that had once existed with Greece receded in the fifteenth century; interestingly, ever since the Italian linguist Giuseppe Morosi ‘discovered’ Griko in the middle of the nineteenth century, the language has been considered to be on the verge of disappearing. Unexpectedly, however, it survived such prophecy. Locals continued speaking it in a few villages until WWII, but stopped transmitting it as a mother tongue; and, under the ‘symbolic power’ of the national language—to use the wording of Bourdieu (1991)—Griko was deemed to be a ‘language of the backward past.’ Together with Calabrian Greek—or simply Greko—which is spoken in Calabria in the ‘toe’ of Italy, [2] Griko belongs to the Southern Italian Greek dialect enclaves. In 1999, National Law 482 recognized Griko and Greko together in one category among the twelve ‘historical linguistic minorities’ on Italian soil, in conformity with the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (1992).

I am sure that my grandmother, ’Ndata, or any other elderly Griko speaker could not have foreseen the more recent developments in the story of Griko, whose already rather paradoxical plot as ‘the ever-dying language’ was about to be complicated further. The current revival of Griko—with everything that entails—originated in the late 1990s, when political tuning and intuition at the local level, coupled with the availability of legal instruments and financial resources at the national and European levels, prompted the positive response of local politicians who historically had been insensitive to Griko and the local cultural heritage. Now sensing not only their cultural but also the economic potential, the mayors of the Griko-speaking villages have collaborated to create the Union of Villages of Grecìa Salentina. Griko and folk music (pizzica) have become “an essential instrument to give sense and meaning to a potential growth and development of our territory,” said Sergio Blasi, then mayor of Melpignano. [3] In the process of that revival, a broader reevaluation of the local cultural repertoire has been enacted in the name of Griko, a reevaluation that incorporates cultural expressions of the larger Salentine individuality and extends to the spheres of music, gastronomy, art, and landscape. The region’s overall popularity has increased, attracting growing numbers of tourists and rendering Salento one of the top tourist destinations in Italy: what was until recently Italy’s finis terrae, or land’s end, is now in the spotlight.

This is particularly telling considering that attempts to raise awareness about Griko and its heritage are all but new; already at the turn of the nineteenth century local philhellenic intellectuals had been engaged in restoring prestige to the language, what I call ‘the first revival of Griko’ (Chapter 1). When, by the mid-1970s, the number of Griko mother-tongue speakers had dramatically decreased, politically sensitive cultural activists began promoting what I label ‘the middle revival.’ [4] The revival was this time not restricted to the language, but included a reevaluation of those indexes of the past that locals had internalized as signs of their own inferiority, including music and local traditions in Griko, but also—and this is crucial—in the local Italo-Romance dialect of Salentine (Chapter 3). Yet these efforts lacked a legal framework that would articulate and legitimize their claims; the 1990s were instead a time in which language rights specifically were the focus of international attention. Indeed, the adoption by the Italian government of Law 482 for the protection of its minority languages (fifty-one years after the Italian Constitution was written!) points to the interplay of transnational and national policies, and ideologies regarding language. The ethnographic account of the situated case of Griko in this crucial moment of transition and opportunity shows the transformative effects of these policies on the ground.

This book therefore recounts the story of Griko, the multiple ways in which locals viewed and used it in the past, and the ways in which they view and use it today. It traces Griko speakers’ multiple ideologies about the language. The lens of language ideologies brings into focus the relationship between language, politics, and identity; Paul Kroskrity defines language ideologies as “beliefs, feelings and conceptions about language structure and use” (2010:192). The term ‘ideology’ should not mislead the reader into thinking we are dealing with ‘ideas’ in contraposition to ‘facts,’ or that some ideologies are ‘true’ and others ‘false,’ as Deborah Cameron stresses (2003); language ideologies are social contracts which are not abstract but rather “enact ties of language to identity, to aesthetics, to morality, and to epistemology” (Woolard 1998:3).

As cultural frames and historical products, ideologies about ‘language’ continuously transcend it and emerge out of various domains of social life; at the same time they act upon them by affecting the very setting in which they originate. Thus, Griko speakers have shifted away from Griko and back to it again by interpreting and reacting to situated social changes, which then recursively affected their ideas about themselves, about their language and its use. Particularly since the end of World War II, Griko speakers had internalized it as a ‘language of shame.’ “Mas èkanne vergogna,”—“We felt shame,” Uccio (born in 1933) from Zollino told me, as do many of his generation. This shift in language ideologies meant that the generation born during the socioeconomic boom of the postwar years was not taught Griko as their mother tongue (Chapter 2). This is the generation that “grew up with one foot in the old world and one in the new world,” as Mario (born in 1961) from Sternatia told me, his words characteristic of what I label the ‘in-between generation,’ suspended between different worldviews associated with Griko and, respectively, Salentine and Italian.

This story’s plot is, in fact, further thickened by the presence of this third linguistic code. What, building on Appadurai (1996), I call the languagescape is constituted not only by Griko and more recently by Italian, but also by Salentine, which derives from Latin, and which locals refer to simply as dialetto (dialect). Together with Sicilian and Southern Calabrian, Salentine belongs to the subgroup of ‘extreme Southern dialects’ of Italian; however, what distinguishes them is the ‘Greek flavor’ of their grammar, the result of the previous presence of the Greek language in these territories. Salentine and Griko have indeed long coexisted in the area, in historical symbiosis, each entangled in the other’s corpus. As my friend Adriana from Corigliano summarizes, “Lu grecu è mbiscatu cu lu dialettu. Ca poi ete lu dialettu ca se mbisca cu lu grecu” (Salentine)—“Griko is mixed with Salentine. And then again, Salentine is mixed with Griko.” Because of its hybridity, Griko was long internalized as a “bastard dialect”—“nu dialettu bastardu” (Salentine).

By languagescape I mean, in fact, not only Griko as a spoken language in the context of other locally spoken languages, but also the metadiscursive landscape surrounding them. However, this is more broadly an Italian phenomenon. The questione della lingua (language question) reflects the history of Italy’s linguistic diversity, which is considered unique in Europe; indeed, in Italy today there are several ‘dialects’ spoken in everyday life, the result of centuries of cultural and political diversity before the unification of the country. [5] The local languagescape today has been influenced by the language ideology promoted by Italian governing forces ever since Italy emerged as a nation-state. The diachronic approach I take in this book in fact captures the varying sociocultural and political landscapes and ideological structures that have mediated the language shift away from Griko and those supporting the various phases of its revival; in addition, the heteroglossic local languagescape I present shows how locals have experienced, over time, blended linguistic realities.

This book does not embark on yet another tired exercise to define the identity of speakers—at least not in the strict sense of that term. Nor does it contribute to the longstanding philological debate about the origins of Griko, which remains a fascinating puzzle to which I will return in order to highlight its ideological underpinnings (Chapter 1). This is neither a “salvage ethnography” nor “salvage linguistics”—to use the wording of James Collins (1998:259); I do not predict the demise of Griko, nor do I prescribe therapies to ‘heal’ it. Here instead I narrate how a variety of social actors (speakers, local intellectuals, language connoisseurs and aficionados, cultural activists, and more recently politicians) have engaged with Griko over time, including shifting claims, aims, and modalities. I highlight how they have built on specific language ideologies to do so, and how such ideologies have simultaneously acted upon the social, political, and economic domains (in Chapters 3 and 4).

Among such social actors figure Greek aficionados of Griko, who have intensified their collaborations with local cultural associations since the 1990s. I therefore investigate the popular but also institutional engagement of Greece in the reproduction and circulation at the local level of a language ideology celebrating Griko as “ena zondanó mnimeío tou Ellinismoú”—“a living monument of Hellenism.” This way the ‘linguistic kinship’ between Greek and Griko (beyond Griko’s hybrid nature) is selectively highlighted by Greek aficionados of Griko, who indeed feel an emotional, almost visceral, attachment to the language and to its speakers, as well as to the very place where, according to Dimitri, “the heart of Greece beats”—“chtypáei i kardiá tis Elládas” (Modern Greek). In addition, since 1994 the Greek Ministry of Education has been sending Greek teachers to the area to teach Modern Greek [6] in public schools and cultural associations. Understandably, this policy has impacted the local languagescape (Chapters 6 and 7).

In short, this book is based on an anthropological study, and in it I provide a purposeful linguistic analysis in order to recount the ‘story’ of Griko through written sources, and through the narratives I have collected both from those who speak it and from those who have engaged/engage with it in different ways. What you are about to read is ultimately my story of their stories, in which I trace how the multiple language ideologies of Griko were and are negotiated locally, in a dialogical relationship with language practices and policies promoted by the European Union, Italy, and Greece. I recount how locals have been generating social relationships, fueling moral feelings and political interest in the process, ultimately transforming the language and its predicament.

Defining my place, contextualizing Salento

Grecìa Salentina [7] is located at the center of Salento. The Salentine peninsula—often called ‘the heel of the Italian boot’—is the southeastern extremity of the Apulia region and the eastern extremity of the Italian Republic. It comprises Brindisi, Lecce, and Taranto provinces. The province of Lecce has a very flat landscape; it is a fertile plain granting an all-encompassing gaze upon the horizon, which appears ever widening. If you raise your eyes, you will find few obstacles—and never higher than two-hundred meters above sea level. You will then see the sea; you are surrounded by two-hundred kilometers of coastline, sandy and rocky. The administrative borders of what today goes by the name Union of the Municipalities of Grecìa Salentina (Unione dei comuni della Grecìa Salentina), constituted in 2001, includes eleven villages (see Figure 2). Griko is still spoken in seven of them: Calimera, Castrignano dei Greci, Corigliano d’Otranto, Zollino, Sternatia, Martano, and Martignano. Melpignano and Soleto counted Griko-speakers until the beginning of the twentieth century. In the villages of Carpignano and Cutrofiano, Griko was spoken until the beginning of the nineteenth century and the end of the eighteenth century, respectively. These same two villages were annexed to the Union of the Municipalities of Grecìa Salentina in 2005 and 2007, respectively.

Figure 2: Map of the extant administrative area of Grecìa Salentina

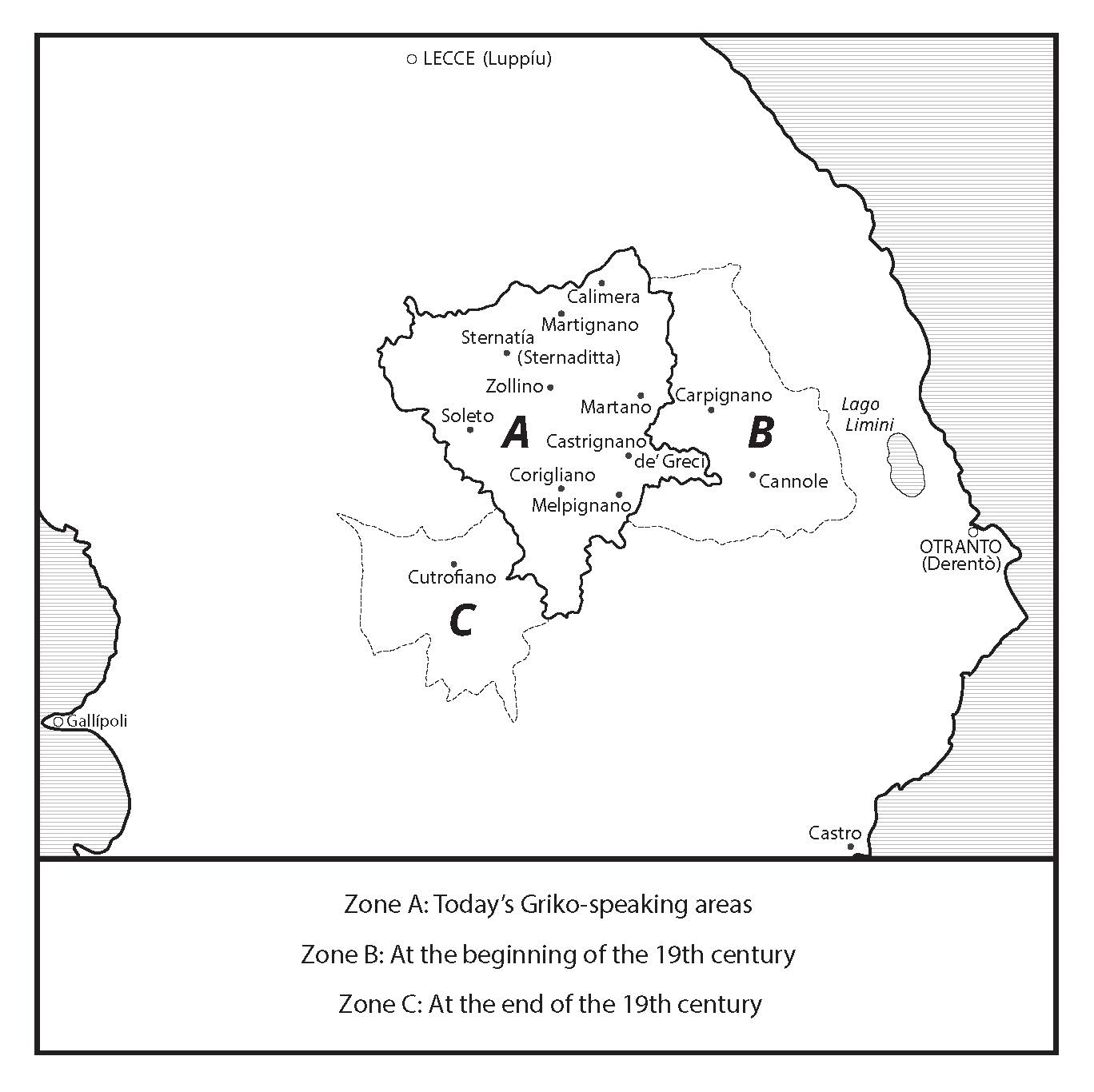

The locals, however, used to refer to the Griko-speaking villages with the expression ta dekatrìa chorìa, referring to a past (the nineteenth century) during which Salentine Greek was spoken in ‘thirteen villages.’ Located contiguously, with the greatest distance between villages being ten kilometers, these villages create a sort of island within Lecce province, representing what is left of a much larger area that gradually receded: in the sixteenth century this territory comprised twenty-four villages; toward the end of the eighteenth century, fifteen villages; thirteen villages in the nineteenth century; then nine in the twentieth century; and seven today (see Figure 3). The Griko-speaking area can be visualized as a ‘puddle’ that has dried up progressively; its outskirts are by definition in contact with non-hellenophonic villages, and its borders have progressively contracted.

Figure 3: Map tracing the progression of the Salentine-Greek speaking area

Yet Salento is known not only for Griko. As early as in the 1950s, it had been the subject of anthropological studies thanks to the research of Ernesto de Martino, the father of Italian anthropology. He investigated the phenomenon of tarantismo, the ritual in which the music of pizzica tarantata was used therapeutically to cure those women (tarantate) who claimed to have been bitten by the tarantula (taranta). In his 1961 book, La Terra del Rimorso, de Martino linked this phenomenon to female existential and social suffering, and understood it as a manifestation of class and gender inequality. Giovanni Pizza (1999, 2004) has stressed the legacy of de Martino’s pivotal work, which was ‘rediscovered’ by Italian anthropologists in the mid-1990s (three decades after his death). Studies have proliferated in recent years around what is now known as neo-tarantism—a contemporary re-appropriation of tarantism—further rendering Salento the “topos of Italian ethnology” (Bevilacqua 2005:74).

By writing about a language that has not been the subject of an anthropological study, [8] my aim is to shift the focus from the much more popular topics of tarantism and neo-tarantism. Yet it would be misleading to refer to the repercussions of Griko’s current revival in isolation from its Salentine surroundings; it would be equally impossible to appreciate fully its dynamics without also considering the revival of folk music, as the two are in a metonymic relationship. The folk music festival of La notte della Taranta, now known internationally, effectively inserted the whole of Salento into the circuit of cultural tourism. Indeed, what de Martino defined at the time as ‘the land of remorse’ has now been turned, I argue, into ‘the land of resource’: Griko and pizzica have gone from signifying backwardness to cultural richness, and become the symbol of the local identity, as well as the trademark of Salento; this has further implications.

This book is therefore not only or narrowly about Griko. Instead, in it I use language as a lens through which to gaze into the past, the present, and the future of this land and its people.

Beyond Endangerment: Language Ideological Debates

Griko and Greko are recognized by Unesco as “severely endangered”; in her analysis of the case of Calabrian Greek, Pipyrou (2016:14) suggests that the approach of national and transnational organizations such as Unesco is motivated by the fact that the “Grecanico language is distinctive and rich yet ‘in danger of extinction.’” Justified through the claim that preserving a language means preserving a unique worldview that would otherwise be lost, the idiom of ‘diversity’ seems to have bypassed the other long-used catchword ‘identity,’ yet without transcending it entirely. The European Charter, with which Italy’s National Law 482 complied, is in fact embedded in a discourse that celebrates the notion of unity in diversity. Moreover, in order to avoid the specter of Western European cultural nationalism—one language, one people, one country—the Charter follows an ‘ecological’ approach that positions regional or minority languages as a threatened aspect of Europe’s cultural heritage. This European and global type of diversity discourse prompts us therefore to expand on previous investigations of linguistic/ethnic revivals, where language was often used to assert a minority identity and not necessarily for the benefit of the minority groups. This is true regardless of the shift from the discourse of identity to the current one of diversity.

A language ideological approach, importantly, allows us to reposition speakers at the center of our analysis, and to recognize their agency—their ability “to interpret and morally evaluate their situation,” to borrow the words of Sherry Ortner (1995:185). If these insights shed new light on situations of language shift, ‘obsolescence,’ ‘endangerment,’ ‘suicide,’ ‘death,’ and ‘extinction,’ the widespread discourse on ‘language endangerment’ transcends the academic realm and appeals to a vast audience; it also engenders a ‘moral panic’ about the fate of languages. [9] Biological and ecological metaphors applied to language (death, extinction) are indeed powerful, but they may also carry dangerous reductions; viewing languages as organisms that are born and die leaves unanswered the question of when one can truly say that a language has died: Is it when the last speaker of such a language dies, or when it stops being used as a medium of regular communication? Linguistic anthropologists have highlighted how such metaphors are therefore essentializing (Cameron 2007; Jaffe 2007) and potentially dangerous, as they reproduce the nineteenth-century view of an unquestioned link between language and ethnicity/culture. An emphasis on ‘natural’ processes, moreover, may end up reinforcing the view that language loss and/or death is equally ‘natural,’ thus deflecting attention away from the role played by sociopolitical factors (Pennycook 2004:216). [10]

In the case of Griko, the moral panic around its impending death has a long history. In the spring of 1867, the Italian philologist Morosi wrote, “Perhaps in less than two generations from now, scholars will only be able to infer that—a century earlier—Greek colonies existed here” (Morosi 1870:182). In spring 2008, Paolo Di Mitri from the village of Martano reflected on the death of Griko in an article for the local newspaper Spitta: “O Grikomma pesane? Refrisko n’achi. Ce mì pu grafome grika, imesta pesammeni? Esi ka mas meletate pesanato? (Has Griko died? May it rest in peace. Are we who write Griko dead then? Are you who are reading it dead then?) [11]

My grandmother Lavretàna died in March 2008, at the age of 104. Griko is still the language of other women and men with white hair and sometimes black clothes. What I found is that, over a century and a half after Morosi’s wistful pondering, locals still deal daily with this pending prophecy: the pool of mother-tongue speakers keeps shrinking, while linguistic competence, if any, varies widely across generations. As James Clifford (1986) argued, proclaiming the extinction of people and languages as soon as they are discovered by outsiders/scholars is indeed part of the Western rhetorical ideology to which ethnography has complied. Yet what may still strike the reader about the apparent paradox of Griko as perpetually dying is that locals’ attempts ‘to keep it alive’ have not been aimed specifically at fostering new speakers—which is typically understood as the aim of language revival and revitalization efforts. Crucially, whether to actively participate in such efforts or to challenge them is ultimately linked to locals’ own language ideologies and their situated interpretations of the revival processes. [12]

An immediate causal relationship between language ideologies and practice is indeed not a foregone conclusion. If for Griko speakers the ideologies of Griko as the ‘language of shame’ had completely won over those of Griko as the ‘language of resource,’ there would be no Griko speakers at all by now, linguistic competence aside. Nothing new or surprising here for anthropologists, who often record inconsistencies between discourse and practice. Likewise, if the ideology of Griko as the ‘language of pride’ had prevailed over its current lack of imperative communicative currency, the pool of speakers would be larger—or at the very least you would expect language activists to be Griko speakers, or to strive to become Griko speakers. This is not the case either. In fact, inconsistencies between ideologies and practices emerge sharply, and the challenge has been to reveal what these inconsistencies hide.

Certainly locals are not silent. In various contexts, I have heard them offer reflexive comments about the current situation of Griko, at times lamenting that today “we talk more about Griko than in Griko.” Indeed, Griko keeps on generating what sociolinguist Jan Blommaert (1999) defines as “language ideological debates”—that is, contentions about language ideologies and not language per se. Old ideological debates persist today about the origins of the language (Chapter 1), or about the varying degrees of agency and the responsibility of speakers in the process of language shift (Chapter 2), while new debates emerge and take center stage. By debating, for instance, how to transcribe it and whether to rely on Italian, the local Romance dialect, or MG to integrate its limited vocabulary, speakers, activists, and local cultori del Griko (Griko scholars) and locals at large reveal their understandings and projections about the role of Griko in the past-present-future (Chapter 5).

It should come as no surprise that Griko means, meant, or is meant to mean, different things to different people of different ages or backgrounds; anthropological studies have attested time and time again to the multiplicity of language ideologies that have been linked to gender, social position, and generation, to mention just a few. Expecting, however, to find a ‘homogeneous’ language ideology within a single social formation would be equally misleading. A crucial tool for this research has, therefore, been to attend not only to locals’ explicit language ideologies but also to their metalinguistic comments—that is, those reflexive and often implicit comments about Griko that, in a performative way, keep shaping the story of this language. This approach has helped me to disentangle the multiple language ideologies present in the community, and to realize how they are often emotionally charged and may be interest-laden. The basic premise here is that language itself is multifunctional, and that its referential function is one of many. [13]

Language is not simply a tool to describe the world, but rather a tool that allows us to connect with it. One of the semiotic processes through which language ideologies are instantiated is indexicality, a term introduced by the semiotician Charles S. Peirce that builds on the notion of index and captures the ability of language to go beyond the semantic meaning of words: through linguistic indexes such as pronunciation, accents, and/or genres, a language reestablishes a connection with places, contexts, groups of people, and moments in time. [14] Crucially, in the case at hand, the language itself functions as an index, as a sort of imaginary arrow, and the object it points to is the past. As one would expect, the past is multifaceted; foremost, it is not simply a temporal category but a critical ideological terrain of self-representation.

Textures of Time

Modern Greek classes: “Back then things were not like today”

It was a rainy evening and the little alley leading to the cultural association Chora-Ma (Griko: My Village) in Sternatia, was particularly quiet. “Pame stin ekklisìa” (MG)—“We go to church”—I heard Eleni say when I entered Palazzo Granafei, the eighteenth-century baroque building that houses the association. The class had started! Since 1994, the Greek Ministry of Education has been sending Greek teachers to the area to teach MG in public schools and cultural associations; Eleni was the appointed MG teacher at the time. The hour passed as usual: Gaetano and Cosimino, two retired Griko mother-tongue speakers from Sternatia, exchanged notes and views comparing MG and Griko, whispering to avoid being scolded by Eleni. “Imi ittù leme itu: aklisìa. To stesso pramma, torì?” (Griko)—“Here we say aklisìa. The same thing, you see?” Gaetano noted, noting with satisfaction the similarity with the MG word ekklisìa.

After the class, as Gaetano and I were walking to my car, I stepped in a puddle and complained that the shoes I was wearing were not suitable for the rain. He intervened, “Scarpe lei isù … tis iche scarpe toa?”—“You talk about shoes … Back then who wore shoes?” That was to be the beginning of yet another conversation about the past, a past whose language of expression was Griko. Gaetano (born in 1947) from Sternatia—who earned his living as a prison guard as an adult—had been a shepherd when he was a child; he started recalling how hard life had been back then, how shoes were only worn on Sundays, that he used to go to work in the fields barefoot, to run on thorns and stones, and how he could not even feel them because the soles of his feet had become so tough. Gaetano here, as many others do, was referring to his own experiential past and his sensorial memories. We reached my car, but he went on talking about the past. “Toa ‘en ìane kundu àrtena”—“Back then things were not like today,” he concluded. It had started raining again.

Griko classes: “Our language is not a bastard, the one who says it is, is the bastard!”

Daniele (born in 1952) was sitting in front of us, hunched over a piece of paper, checking the spelling of poems written by the class. At the time, every Thursday afternoon, he taught an intermediate Griko class organized by the cultural association Kaliglossa (Griko: Good Language) based in Calimera. He is a retired computer programmer with a degree in astrophysics, but with an early background in and vivid passion for classical studies. Once the lesson was over, Daniele and I continued to talk about some issues that had arisen during the lesson.

For instance, if you write lio nerò—‘a bit of water’—you pronounce it as it is, but lio comes from oligon, and since there is an elision, you have to pronounce the consonant of the following word as double—lio nnerò—but how to spell it then? It is ugly to start with a double consonant. With all due respect it would look like an African language; it could wake up old prejudices … our language is not a bastard, the one who says it is, is the bastard! Some used to say Griko was a barbaric language … calling it barbaric when we … when our ancestors invented the word … it would be an absurd historical anamnesis, for Griko contains traces of Hellenism!

Daniele here is vehement about disassociating Griko from its longstanding negative perception as a ‘bastard language’; hidden behind philological and orthographic issues, he indeed makes a clear claim to a distant but ‘glorious Hellenic past’ also influenced by the romantic ideology of Hellenism. Gaetano instead refers to his own experiential memory of the hardship of a relatively recent past immersed in the subalternity of the South. They ultimately make different references and claims about the past that Griko points to. Given the small gap in their ages, this difference is more attributable to their differing backgrounds and life experiences. Daniele’s knowledge about Greek history and view of Greek as the language of culture were, for many years, unusual outside of the intellectual world. Moreover, there are no popular accounts of the origins of ancestors or the language (of the kind that Tsitsipis [1998] found among the Arvanites of Greece); so, for generations, the majority of Griko speakers commonly ignored the cultural wealth of Greek (Parlangeli 1960); elderly speakers may still do so today.

Through the current revival, however, Griko speakers and locals at large have now been informed—reminded, as it were—about the noble origins of the language. Among them is Gaetano himself, who has been attending MG classes for years, and who is a main resource for Greek tourists and aficionados who visit Sternatia; he understandably enjoys his popularity now. The formulaic expression “Toa ‘en ìane kundu àrtena”—“Back then things were not like today”—that Gaetano used, and that the elderly use time and again, captures how the past and present keep being dialogically compared and contrasted; yet what now prevails is a discursive reevaluation of Griko, which is not perceived anymore as a ‘language of peasants’ or indicative of a backward past. Through this ideological shift, locals reevaluate the past associated with speaking Griko, together with all indexes, which become forms of ‘cultural capital.’ This increased prestige happens not only despite the level of language endangerment; I would also argue that the increase in cultural capital occurs in part by virtue of the level of endangerment. The Griko community largely conforms to what Netta Rose Avineri has defined as a “metalinguistic community”; that is, one “of positioned social actors engaged primarily in discourse about language and cultural symbols tied to language” (2014:19). As in the case of the Yiddish she describes, it is through speaking about Griko, rather than speaking it, that linguistic identities emerge. In the case of Griko, furthermore, it is by engaging with and evoking the multiple pasts of Griko that locals provide community self-representations.

Rather than a ‘revival of Griko’ per se, I consider this a ‘language ideological revival,’ as what has been revived or revitalized is not the language itself, but instead ideas, feelings, and emotions about the role of Griko in the past. In the process, locals now blend autobiographical references and experiential realities with historiography and global discourses about cultural diversity. The people I introduce in the pages that follow—speakers, cultural activists, language connoisseurs, politicians, and locals more broadly—are not only the protagonists and the tellers of this story, they are also its very writers; they ‘rewrite’ the story of Griko, as it were, by recounting its multiple pasts. In the process, however, this generates tensions. As the vignettes indicate, the past remains a highly contested terrain: the questions of which chapter of Griko’s past locals recall and build on to reconstruct its story, and which chapter of Griko’s past from the multiple repertoires available best represents Griko and is best represented by it, become discursive struggles for community self-representation. The discursive practice of evoking the past indeed links locals to a network of earlier experiences and/or discourses, anchoring Griko to a specific time-space framework—to what the theorist Mikhail Bakhtin (1980) referred to as a chronotope—and enabling them to identify and represent themselves. To restore the past means equally to re-story it; this way, Griko becomes a metalanguage for talking about the past in order to position oneself in the present.

I therefore introduce the concept of the cultural temporality of language, which aims to capture the multiple relationships locals entertain with the language through its past, and with the past through language. While temporality has been understood as either a cultural relationship with time or as a phenomenological sense of time, I use the term here to emphasize how language stimulates temporal thought and talk, and how these are generated by cultural models and accounts of past-present-future; that is, by multiple historicities in the sense given to this term by Eric Hirsch and Charles Stewart (2005:262). In cases of minority languages involved in processes of so-called endangerment and revival, the ways in which members of the community experience and/or construct the past become central. In the case of Griko, locals do not challenge linear representations of temporality as such; rather, they engage systematically in ‘evoking the past’—Griko’s multiple pasts—and the very textures of that past: its glory, its hardship, its opportunities and its failures.

This is why I integrate the cultural, in order to stress how language is itself anchored in time and space as a material presence. By evoking the recent past locals in fact evoke its textures together with their morally and emotionally loaded aesthetic values, which in turn affect language ideology and practice in the present and future. In this sense I am in intellectual dialogue with the theoretical strand of language materiality that has recently emerged, and that specifically proposes “to view language as a material presence with physical and metaphysical properties and as embedded within political economic structures”—to use the words of Jillian Cavanaugh and Shalini Shankar (2017:1). Through the materiality of language, its sounds and form, language ideologies are therefore linked to locals’ lived experiences and memories of language use, as is often the case with minority languages gone into disuse.

Being socially distributed, however, such ideologies may equally rest on projections of a temporally distant but glorious past, a past which connects Southern Italy and Greece, and which in turn also influences language choices and ‘tastes.’ This phenomenon highlights how language ideologies linked to a specific historicity may reinforce cultural ties between contemporary Italy and Greece, connecting communities across national borders as the ongoing contact with Greek aficionados of Griko attest. Since the 1990s, the intensification of contact with Greece, the availability of MG courses provided by the Greek Ministry of Education, and the interest shown by Greek aficionados of Griko who visit the area have been adding new layers to the unfolding Griko ‘story.’ In the midst of economic, demographic, and sociopolitical changes affecting southern Europe, the ideological alignment to the Hellenic cultural heritage as an idiom of global belonging and as “a preordained category of relatedness” (Pipyrou 2016:10) takes on broader sociopolitical meanings. In fact, depending on which past is evoked, Griko becomes a symbolic resource from which to write a different future.

Traces of Language

The journey from Soleto to Calimera is a short one. As I often do, I chose to drive through the villages of Sternatia and Martignano in order to enjoy the embrace of the landscape, its countryside, and the forest of olive trees swaying gently. That afternoon in late fall, the warm sunshine was still assured. Luigi from Calimera (born in 1963) wanted to update me on the progress of his album of songs written in Griko; he defines himself as an operatore culturale (literally, a ‘cultural operator,’ a term that bridges into activism), and although he has spent more than half of his life teaching in Bologna, he is one of the most passionate people about Griko that you will ever meet. His mother, Gilda, was a Griko mother-tongue speaker, but he learned Griko growing up in Via Atene, with his grandmother and her neighbors—mainly war widows and zitelle (Salentine: ‘unmarried women’), he says. He belongs to the ‘in-between generation,’ that was not taught Griko as their mother tongue, and whose linguistic competence is often only partial (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: The village of Calimera. Credit: Daniele Coricciati

Luigi speaks MG and continues to improve his Griko; he talks about his project in very humble terms and describes the lyrics as simple, with his goal being for “the language to resound in its simplicity.” Yet he is also very proud of his achievement. His songs are indeed full of references to love, to memories of the past, and to the language itself; they are the result of a musical adaptation, as they were conceived as poems. Luigi defines Griko as “e glossa ti' kardìa, e glossa pu milì i kardìa”—“the language of the heart, the language that the heart speaks.” Experiential echoes of language fuel this affective attachment towards the language as “the language that the heart speaks.” That is, the emotional textures Griko evokes are linked to the speaker’s memory, and are ultimately fueled by the affective attachments that locals feel towards the people they associate with Griko. [15]

Luigi is equally vehement in stressing how important it was for him to learn about the noble past, as it were, of Griko; this sparked his intellectual interest rather early in life, and drove his subsequent efforts to valorize it. His account in fact shows how affect engenders a sense of moral responsibility towards both the people and the predicament of Griko itself. He continues:

We often play with memory, with nostalgia, and some emotions help us more than others. But sometimes we direct our gaze from the past, which we believe we know, to the unknown future. So, what counts the most is our desire and hope to be part of it, to carve the language and ourselves into somebody else’s memory forever. Yet this is not only a need but also a duty.

The cultural temporality of language is indeed produced by the intersection of affect and morality, which then impacts language ideology and practice. As one might expect, what is considered to be ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ for Griko is contingent, perspectival, and highly contested—and this points again to the multiplicity of social actors engaged in the story of Griko, and to their clashing claims about the past and thus the future of Griko (see Chapter 5). Luigi, for instance, has fulfilled his duty, as it were, by leaving evidence of the language in the form of songs and poems. Throughout time locals have indeed left such ‘traces of language.’ In this respect the category of local cultori del Griko (local ‘scholars of Griko’) acquires an even stronger relevance with regard to the management of the Griko cause, since they have dedicated themselves to documenting the language. At the same time, as the etymology of the word cultore itself (from Latin ‘cultivate,’ ‘worship’) suggests, they have ceaselessly ‘nourished’ Griko over the years, further filling its materiality. The collection of oral popular culture compiled in the past, as well as their own production of new poems, songs, and other writings over the course of time, represent a material legacy through which locals keep building connections between language and people, times and place in the present (Pellegrino 2016a).

Used as a form of cultural capital, the symbolic value Griko has acquired transcends its use as a medium of daily communication. The overall pool of Griko speakers shows in fact varying degrees of competence; age remains one of the decisive factors, a temporal marker of the distance since the shift away from Griko. This is often the case when a language shift takes more than one generation, and takes place through a restriction in the language communicative functions. In particular, this means that those who belong to the younger generation are bilingual in Italian/Salentine, and in fact cannot be defined as Griko speakers in prescriptive terms. If they have any, their competence in Griko varies considerably and depends on their degree of exposure to the language, which in turn is strictly related to the time spent with their grandparents and the elderly in general. In such a language ideological revival, however, those who have actively engaged or engage in either improving their competence or in acquiring it represent ‘a minority within a minority.’ [16]

In this book I therefore demonstrate the semiotic relevance of all ‘traces of language,’ highlighting the multiple ways in which locals engage with Griko, and the creative ways in which those who belong to the in-between and younger generations may resort to it (Chapter 6). Inspired by the work of sociolinguist Ben Rampton, I call these instances ‘generational crossing,’ with “crossing” referring to “the use of a language which is not generally thought to ‘belong’ to the speaker” (Rampton 2009:287). [17] In the case at hand, Griko is perceived as the language of the elderly and of their experiential world, a world that the younger generation has not inhabited, and that the ‘in-between generation’ has only experienced in passing. However, the younger and in-between generations resourcefully decontextualize and recontextualize the limited linguistic resources available to them, and by crossing the generational distance between the elderly and themselves, they perform an act of symbolic identification with them, and with the cultural repertoire.

In this book I therefore deconstruct the notion of ‘language death’ by emphasizing the functions of language that transcend its referential and indexical meanings, demonstrating how multiple forms of language practice become socially and culturally meaningful for the locals as ways to re-present themselves beyond the use of Griko for mere communicative purposes, and despite its selected and limited use. [18] No one can deny that Griko has remained a linguistic resource for a minority of the locals, but I contend that it never stopped being perceived as a resource; it was a resource even when it was perceived as a language of shame (Chapter 2). I therefore move to deflect attention from the moral panic about the endangerment and extinction of Griko, and highlight instead its mobilization as a cultural resource that has become productive of personal values and social relations—but also, and crucially, a catalyst for the articulation of multiple claims.

The power game of minority politics

As I show in this book by tracing the various phases of the revival of Griko, the very social actors who promoted them shifted over time, as did their claims and aims; the educated middle class philhellenists of the first revival pursued ‘recognition’ of the value of Griko, while the politically engaged ‘generation in between’ of the middle revival aimed at the ‘redemption’ of the Southern Italian past and its indexes. The management of Griko and cultural heritage at large, instead, was adopted by local politicians, engendering tensions and conflicts within the community at large. Similarly, Stavroula Pipyrou (2016:11), with reference to Calabrian Greek, has highlighted how questions of ownership emerge, as well as conflict and contestation as to who has the right to represent whom through language. She captures the plurality of actors involved in the management of the Calabrian Greek language and culture by deploying the concept of fearless governance—meaning here how they have developed the means to participate actively in the power games of minority politics. Significantly, they have done so by appropriating the available political and bureaucratic channels of governance rather than being subject to them; she argues that they have successfully promoted self-governance and inverted hegemonic culture (2016:6).

In the case at hand, a variety of social actors reclaim a space in the management of Griko and the right to participate in it. It is indeed highly disputed not only who retains authority over the language (its speakers, language connoisseurs and experts, cultural activists, or politicians) but also what defines it (whether linguistic competence, philological expertise, active engagement, or political entrepreneurship). Since in terms of linguistic competence, few people ‘master’ the language, this minority enhances its cultural capital, but the phenomenon also produces debates and conflicts over linguistic and cultural ownership, often also provoking frictions and estrangements among them (Chapter 5) and extending to the management of cultural heritage more broadly (Chapter 4). Moreover, as Pizza (2004, 2005) claims regarding the phenomenon of tarantism, conflicts framed over linguistic/cultural ownership may also be metacomments about the division of labor, and disputes over access to the symbolic and financial resources provided by the revival.

In what follows, I reveal a picture of Grecìa Salentina—and hence Salento—that is far from the homogenized one portrayed on global stages and often reproduced rhetorically locally. The case of Griko shows how the dynamics of the current revival have progressively led to a sense of discursive pride in the rediscovered value given to the language, its past, and to cultural heritage, which may be generic and superficial, as well as deeply felt or strategically articulated. Yet this scattered feeling of empowerment not only generates debates about the role of Griko in the future, but hides locals’ fears of losing control over cultural ownership and what this may entail. Crucially, in a place such as Salento that has long been the subject of the anthropological gaze, and where cultural politics and the politics of culture have been dominant, issues of authenticity and authority turn into a struggle for representation.

Methods and relationships: Anthropology and home

This book is the product of multi-sited research and ethnographic evidence collected in Grecìa Salentina and in Greece. [19] Yet my interest in Griko goes way back, as I originally come from Zollino, the home of my father (1932–2014), and my home until my early twenties; this makes me a native anthropologist. [20] My own positionality therefore merits some discussion. Increasingly scholars are expected to recognize the inevitable ideological dimension inherent in their work; in this vein, I highlight from the start that I used anthropology as a tool to scrutinize my own reality and give meaning to the story of Griko. My father, a proud man from ‘the old world,’ never quite understood my need to put on paper what, he claimed, was already written on his skin. Before his death he acquiesced, but added a proviso: “Enna to grasci? Teli daveru na to grasci? Ma, enna to grasci kalà, kui?” (Griko)—“Well, if you really have to ... if you want to, then don’t make any mistakes, OK?” Keeping my word to him in writing this book has been a years-long effort, an emotional challenge as much as an intellectual endeavor.

When I first started my fieldwork in Italy, I spent four months in Zollino and ten months in the village of Soleto, five kilometers away. In Zollino, acquaintances, neighbors, family friends, relatives, and my own parents—my mother is from Martano—were my resources. In the nearby villages, my interlocutors and I engaged constantly in a mapping exercise, which would end only once the relative/friend/acquaintance we had in common was identified; this usually granted me a warm welcome to their homes and unconditional access to their story worlds and their pasts: it made of me one of them. Common languages (Italian/Salentine and then Griko) and shared social norms (cf. Gefou-Madianou 1993) certainly rendered my role as a researcher easier.

The physical proximity of the villages, combined with the relatively small number of people involved, made conducting qualitative research manageable. I engaged in two main kinds of investigation: first, I attended to everyday linguistic practices and embedded ideologies, and moved away from the prescriptive/descriptive linguistics tradition, focusing instead on the study of language in context, on what speakers do with language, and on the cultural rules they follow. But I was equally interested in investigating the politics of the revival; to that end, I identified the main social actors involved in the middle and the current revivals. Because I already knew those from Zollino, it was easy to identify those in the nearby villages, which again facilitated my work. On the other hand, at times being ‘one of them’ made my questions sound weird and redundant, as my interlocutors expected me to “know the answer,” or to have heard it before—which indeed I often did and had. In those cases, I had to reassure them that I was interested in their personal views, not just the common understanding. This also made me feel frustrated, for I imagined that if I had been a foreign researcher, someone not known to them, any question would have been plausible.

Part of my ethnography consisted of collecting and recording elderly Griko-speakers’ life histories in Griko and/or Salentine, the two languages between which they often alternate. The speakers mainly come from the villages of Sternatia, Zollino, Martano, and Corigliano (see Figures 5-8), and I employed a narrative analysis approach to dissect their stories. Even when I explicitly asked them to recount their memories of the progressive shift away from Griko, my elderly friends constantly compared and contrasted past and present. As you might expect, they were not only talking about themselves and their own lives, they were also indexing collective experiences.

Figure 5: The village of Zollino. Credit: Daniele Coricciati

Figure 6: The village of Sternatia. Credit: Daniele Coricciati

Figure 7: The village of Martano. Credit: Daniele Coricciati

Figure 8: The village of Corigliano. Credit: Daniele Coricciati

In these encounters with elderly Griko mother-tongue speakers, it became particularly apparent how being/not being one of them was a constantly shifting and negotiable concept, for me as much as for my interlocutors. In other words, I had indeed to learn quickly that “the grounds of familiarity and distance are shifting ones,” as Marilyn Strathern put it (1987:16). What put distance between us was my age. Countless times they told me, “Toa en' ìane kundu àrtena”—“Back then things were not like today.” Indeed, I did not inhabit the experiential reality of the past, hardships included, as they did. Yet there was more to it than that. My elderly friends not only had lived a past of which I had no experience, they also lived in a world they recall and narrate in a language they feel is theirs, and that is not my mother tongue. Although over the course of time, they welcomed and encouraged my attempts to learn and speak Griko, my elderly friends initially told me that speaking Griko to me did not come naturally to them (‘E’ m’orkete na kuntèscio Grika 's esèna). This should come as no surprise since Griko is perceived as a language that belongs to the elderly. Indeed, when I began the fieldwork, my Griko consisted of a limited stock of words, sentences, and formulaic expressions; learning Griko meant spending time every day with elderly villagers, mainly from Zollino and Sternatia. That, in turn, meant visiting them in their homes—learning to make pasta with Maria, drinking coffee with ’Ndata, accompanying Antimino when he went to water his orchard, etc. I quite simply followed them around on their daily activities and reminded them that I wanted to learn Griko. It was a slow process, one in which they made fun of my mistakes, taking revenge, as it were, against the “young” people who often make fun of their mistakes in Italian. This process of negotiation that is at play in any ethnographic encounter here acquired a further dimension, and over time it allowed us to bridge the generational/experiential gap and communicate in Griko. Antimino, more recently, took all the credit in front of other villagers and proudly announced, “Ivò ti' màttesa to Griko”—“I taught her Griko.”

In reality my fascination with this language started early in life. So I was not surprised when I stumbled upon an old notebook of Griko from my secondary school years, in which I had jotted down every sentence my grandmother would say while living in my parents’ house. I had started learning French at school at the time and, modeling my French textbook, I scribbled in this notebook some Griko ‘rules.’ This was the product of my tortured and no doubt tiresome attempts to decipher them during long winter nights sitting by the fireplace with my father, who patiently tried to answer my questions. This fireside scene shows not only my personal and emotional involvement with the topic, but crucially the role of memory—and not just mine—in retrieving images of the past as they are linked to the language and its use.

Ethnography in Grecìa Salentina

The ethnographic study of Griko cultural associations (associazionismo) constituted a large part of my fieldwork. I conducted semi-structured interviews with the leaders and members of the most active cultural associations engaged in the Griko cause; as one might expect, the initial interview would often end up being only one of many long conversations; I continued meeting with some fairly regularly. I worked with a variety of people, not always those who were part of a specific association. Each in his or her own way shared a commitment to the language and to the place; among them were cultori del Griko (scholars of Griko), authors of Griko grammar books, authors of poems and songs in Griko, amateur linguists, appassionati di Griko (Griko aficionados/enthusiasts), operatori culturali (cultural operators/activists), local intellectuals, and artists, singers, and musicians. Clearly, at times these categories overlapped. I participated in and observed a variety of local cultural activities, such as music festivals, seminars, a poetry competition, public debates, etc. I enjoyed local food at the two ‘historical’ taverns in Sternatia—Mocambo and Lu Puzzu—where people who were engaged in the revival typically met, and where live pizzica music was performed.

For my investigation of the application of language policy (Law 482) with regard to education, [21] I undertook participant observation of weekly Griko classes in primary schools, rotating through the villages of Grecìa Salentina (GS) over a two-month period. I conducted semi-structured interviews with schoolteachers and esperti di Griko (Griko experts; that is, teachers specifically trained to teach Griko) and collected samples of teaching material when permitted. I also conducted semi-structured interviews with the mayors of each village of GS in order to assess how they were applying Law 482 in other activities.

I collected any type of material I could find regarding Griko, including CDs, newspapers, reports, and publications produced by cultural associations. I also conducted diachronic research using past newspaper articles on the topic of Griko and Grecìa Salentina, and by going through the archive provided by the Museum of Griko Culture and Peasant Society (Museo della civiltà contadina e della cultura grika) in Calimera. In addition to this, I conducted online ethnography of various forums about and in Griko, locating metalinguistic discourse and, when applicable, individual language preferences. I read the official website of Grecìa Salentina and the websites of the various villages, registering popular topics and metadiscourses.

Ethnography in Greece

Investigating the production/reproduction and circulation of language ideologies of Griko led me to follow the network of collaborations between Greece and Grecìa Salentina. “Empirically following the thread of cultural process itself” (Marcus 1995:97) indeed impels multi-sited ethnography. This was therefore a choice dictated by the very nature of the subject of inquiry.

When I began my fieldwork in Greece in 2009–2010, I was based in Athens, where I initially attended Greek classes. Being based in the capital also allowed me to investigate the engagement of Greece in the Griko cause at the institutional level. In order to follow the network of collaborations between Griko and Greek associations, I traveled widely within Greece (Salonika, Ioannina, Patra, Corinth, and Corfu) and interviewed the social actors involved. It is important to stress here that before arriving in Greece, I had already made a list of people to interview. During my fieldwork in Grecìa Salentina, I systematically asked each of my interlocutors for the names of their contacts in Greece, those with whom they had collaborated or still collaborate. This web of contacts took me even further afield, and the list of people grew over the course of the research.

Not surprisingly, research among different segments of the population continually overlapped. I had the pleasure of meeting various Greek scholars who engaged with the Griko case, or on related issues; I also collected newspaper reports on the topic, and participated in musical events that included Griko speakers. I was exposed to a variety of contexts, which enormously benefitted my learning and observation, and I was attentive to both unconscious and metalinguistic observations about Griko and Grecìa Salentina (as well as about MG and Greece). Observations deriving from my stays in Athens over the years, as well as on the island of Ikaria, are equally part of the data from which I draw my analysis.

Structure of the book

The book has seven chapters plus a conclusion; the first three chapters look at the ‘past of Griko,’ while the remaining four chapters are devoted to ethnographic study of the present. It could have started from the last chapter; indeed, you may start reading this book from its end and then work backward through its previous chapters. I could have developed each chapter into a book—I am sure many authors could/would claim the same. Of course I could have structured it differently, I could have organized it by theme instead of following a chronological path. I have been saying for years as a sort of mantra that I became an anthropologist because I wanted and needed to explain the story of Griko to myself before anyone else. And I could not find any better way to trace the path leading to the current state of affairs of Griko than to start ‘from the beginning.’

My other conviction, which was at the same time a stumbling block, has long been that ‘capturing the present’ is in a sense a delusive endeavor—no moment in time can be stopped, hence fully captured, so the ‘present’ of any anthropological work is itself ‘history’. However, this is also just half the job anthropologists are called upon to perform. It is somehow ironic—or just obvious?—that in the process I had to deal with my own conceptualizations of how time unfolds, and to face its limitations. Yet the diachronic approach I adopted not only reflects and responds to my personal beliefs as well as anxieties, but it is what holds this book together. With these methodological and conceptual considerations in mind, what follows is the story of Griko.

Footnotes

[ back ] 1. Griko is the Griko word for ‘Greek.’ The traditional label in Italian is Greco Salentino (Salentine Greek), although Griko has prevailed in common use; in this book I will use both interchangeably. When referring to the community as a whole and to its individual speakers, I will use the terms Griko speaking and Griko speakers.

[ back ] 2. It is also known as Grecanico; more recently Greko (literally ‘Greek’) has prevailed. In Modern Greek common parlance, the Griko- and Greko-speaking villages are generally defined as ta ellinofona choriá, literally, ‘Greek-speaking villages’ (both for Apulia and Calabria); these linguistic enclaves were re-discovered by the German philologist Karl Witte in 1821; in Greek literature Griko and Greko are referred to as dialects, and in common use, they generally fall under the label katoitaliká, literally ‘Southern Italian.’ I conceptualize Griko as a language, as locals do.

[ back ] 3. From the introduction to La tela infinita (Mina and Torsello 2005), my translation.

[ back ] 4. According to the official surveys dating back to 1901, 1911, and 1921, the percentage of Griko speakers was 89.3%, 87.8%, and 66.3%, respectively, within a total population that increased from 22,519 inhabitants in 1901 to 24,172 in 1921. According to a study provided by Spano (1965:162) in the mid-1960s, at the time there were about 20,000 Griko speakers.

[ back ] 5. See De Mauro and Lodi 1979; Telmon 1993; Tosi 2004. From the fall of the Western Roman Empire to the Unification of Italy the territory was divided into various states and cities; through the ‘Romanization’ of the peninsula, Latin spread as a written language, but it was spoken differently because it was influenced by the ‘substrata’ of languages spoken before Romanization. In reality, the so-called ‘Italian dialects’ are themselves unofficial languages that are not varieties of Italian, but distinct Italo-Romance varieties; these developed from Latin at the same time as Florentine, which was selected as the national language at the time of the unification of Italy. I use the terms Salentine, Romance dialect, and Italo-Romance dialect interchangeably throughout the book.

[ back ] 6. MG hereafter to refer to Standard Modern Greek.

[ back ] 7. Greeks tend to translate it as Elláda tou Saléntou or Salentiní Elláda (Salentine Greece). To be sure, in Italian ‘Greece’ is Grecia, without the accent mark. The term Grecìa is an artifact—one that has acquired a widespread currency since the latest revival; crucially, the accent put on Grecìa serves to distinguish it from Greece as nation-state. The first written reference I identified dates to 1929 in the title Da Soleto e la Grecìa Salentina by Giuseppe Palumbo, cited in Aprile (1972:26).

[ back ] 8. The existing literature about Griko is mainly linguistic in nature. This is in contrast to Calabrian Greek, which has been the focus of anthropological studies as early as the ‘80s (see Petropoulou 1995, 1997, and more recently Pipyroy 2016). For sociolinguistically oriented research, see Profili (1996); Romano, Manco and Saracino (2002); Romano (2016, 2018); Sobrero and Miglietta (2009, 2010), among others.

[ back ] 9. A moral panic is a “condition, episode, person or group of persons [that] emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests” (Cohen 1972: 9). Cameron (1995: 83) draws from Cohen, and argues that “a moral panic can be said to occur when some social phenomenon or problem is suddenly foregrounded in public discourse and discussed in an obsessive, moralistic and alarmist manner, as if it betokened some imminent catastrophe.”

[ back ] 10. Scholars have increasingly warned against the commodification of a discourse of ‘moral panic' surrounding so-called language endangerment, both in academic and lay discourses (see Duchêne and Heller 2007; Hill 2002; and Silverstein 1998, among others). Such discourse is then further articulated through the notion of rights, those of the speakers to preserve their language and/or of minority languages themselves to be preserved against dominant ones and the specter of globalization (see Coluzzi 2007; May 2001; O’Reilly 2001; Skutnabb-Kangas and Phillipson 1995).

[ back ] 11. Excerpt from an article by Paolo Di Mitri published in the local newspaper Spitta (April 2008). Paolo, who writes in Griko today, belongs to the ‘in-between generation.’

[ back ] 12. Language revival and revitalization efforts may prove to be elusive; this happens at times because educational programs conflict with community goals (Meek 2007) or pedagogical approaches (Nevins 2004), and this may lead speakers to develop strategies to resist language policies based on the acceptance of/challenge to dominant language ideologies (Jaffe 1999).

[ back ] 13. Malinowski (1923) long ago talked about the “phatic function” of language as performing a social task as opposed to conveying information. This notion was further developed by Jakobson (1960), who extended the range of metalinguistic functions to include the referential, poetic, metalingual, conative, and emotive.

[ back ] 14. For early treatments of indexicality see Silverstein (1976, 1992), who builds on the work of Peirce. See also Ochs 1992.

[ back ] 15. See Cavanaugh 2004 on the case of Bergamasco, a vernacular spoken in the Italian region of Lombardia; her concept of “social aesthetics of language” captures precisely the “interweaving of culturally shaped and emotionally felt dimensions of language” (2004:11).

[ back ] 16. The very terminology used in the study of language shifts and death to define linguistic competence is telling. Dorian (1982:26) was the first to introduce the term ‘semi-speaker’ now widely used to define “individuals who have failed to develop full fluency and normal adult proficiency [in East Sutherland Gaelic], as measured by their deviation from the fluent-speaker norms within the community.” ‘Semi-speakers’ seems to me to ‘amputate’ speakers in comparison to a full-bodied abstract ideal speaker. Tsitsipis’s proposed label of ‘terminal speaker,’ which defines his Arvanitika speakers of a young age, has not proliferated—fortunately, I add. This is why I, in contrast, highlight the heteroglossic local languagescape by avoiding a competency-based taxonomy and employing one related to age ranges.

[ back ] 17. Rampton specifically refers to white, Asian, and Caribbean British adolescents who borrow and mix codes as a way of crossing ethnic boundaries.

[ back ] 18. Scholars have highlighted how, even when locals show little interest in revival efforts, languages may become emblems of identity and local culture, and acquire a symbolic value despite their limited use in interactions. See Coupland 2003 for Welsh; Paulston 1994 for Irish; and Fellin 2001 and Cavanaugh 2009 for Italian dialects.

[ back ] 19. I began to conduct fieldwork in Grecìa Salentina in 2008 and in Greece in 2009 as part of my PhD research (2013). While writing my doctoral thesis I was involved in a European project that addressed the lack of teaching material for Griko as the author of the first of four levels of Griko textbooks (Pos Màtome Griko, “How We Learn Griko”). This experience, together with ten hours of teaching Griko in Zollino primary schools, demanded further reflexive interrogation, and further shaped my analysis of the data.

[ back ] 20. The pros and cons of conducting ethnography at home were extensively commented upon and debated when the topic was in vogue in the late 1980s and through the ’90s. Since there is no view from nowhere, my personal experience indicates that the very grounds on which the distinction between anthropology and anthropology-at-home is based are shaky ones, and ultimately the perceived pros and cons of both endeavors neutralize the dichotomy.

[ back ] 21. National Law 482, which recognizes twelve historical linguistic minorities on Italian soil, dates to 1999, but Griko was introduced in local schools in 2002.