-

Katherine Kretler, One Man Show: Poetics and Presence in the Iliad and Odyssey

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. The Elements of Poetics and Presence

2. Marpessa, Kleopatra, and Phoenix

Interlude 1. Ring Thinking: Phoenix in Iliad 23

3. Half-Burnt: The Wife of Protesilaos In and Out of the Iliad

Interlude 2. A Source for the Iliad’s Structure

4. The Living Instrument: Odyssey 13–15 in Performance

Conclusion

Appendix A. Rhapsodes in Vase Painting; Rhapsōidia

Appendix B. The Homeric Performer, the Staff, and “Becoming the Character”

Bibliography

Interlude 1. Ring Thinking: Phoenix in Iliad 23

A full account of the theatricality or performability of Phoenix’s speech involves features such as structure, image, and mythological background. This Interlude shows how these features carry forward from Book 9 to reappear in the narrative of Phoenix’s other major appearance in the poem, in the Funeral Games of Book 23. Somewhat as the second panel of his speech, the Litai parable, mapped the workings of that speech from within, the imagery, mythical allusions, and spatial relations of the Book 23 narrative resonate with his Book 9 speech. These resonant features from Book 23 do more than confirm and deepen some of our findings from the last chapter; they also implicate the character of Phoenix within a nexus of myth and image that appears outside the Homeric poems—especially in visual art. Thus this Interlude expands the mythological discussion outward from figures such as the halcyon to the mythological background of Phoenix himself. Phoenix, like Eris and other figures, has a certain kinesthetics or schēma that works in synergy with image and story. It could be that the performativity of Phoenix’s Book 9 speech brings into the realm of solo performance dynamics seen elsewhere in story and in art.

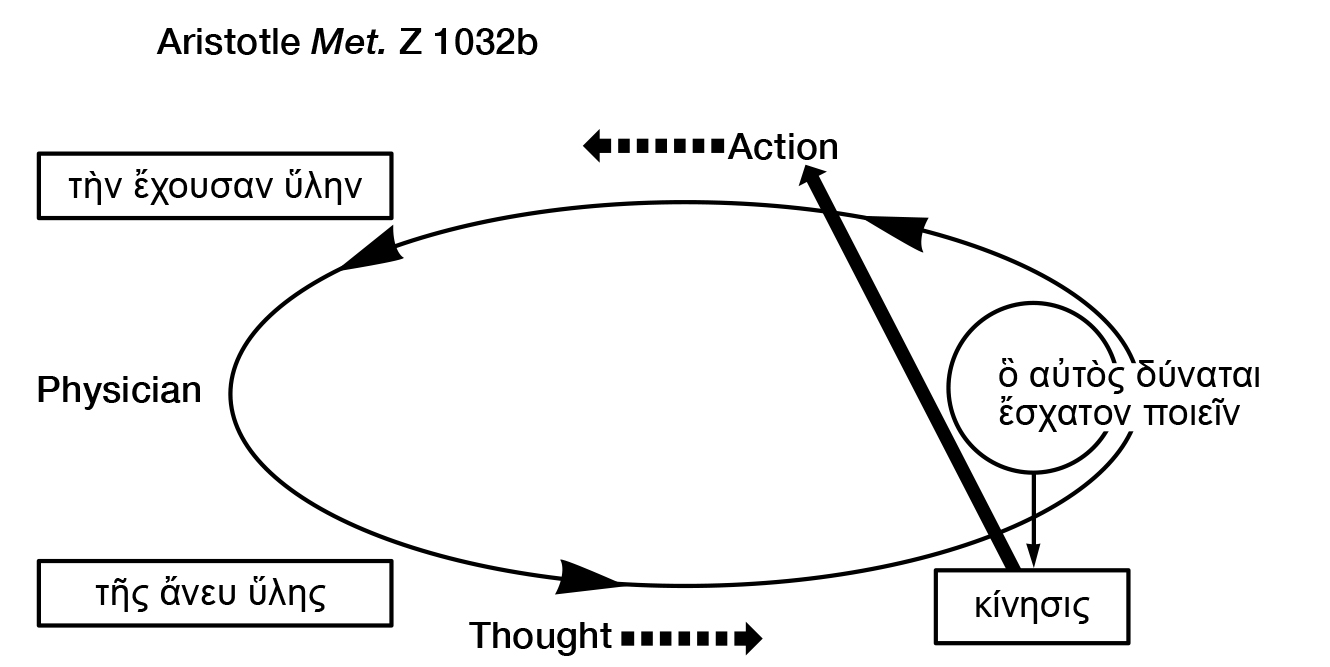

Aristotle maps out the movement of thought to action in the Metaphysics (Z 1032b 6–14) as follows:

γίγνεται δὲ τὸ ὑγιὲς νοήσαντος οὕτως· ἐπειδὴ τοδὶ ὑγίεια, ἀνάγκη εἰ ὑγιὲς ἔσται τοδὶ ὑπάρξαι, οἷον ὁμαλότητα, εἰ δὲ τοῦτο, θερμότητα· καὶ οὕτως ἀεὶ νοεῖ, ἕως ἂν ἀγάγῃ εἰς τοῦτο ὃ αὐτὸς δύναται ἔσχατον ποιεῖν. εἶτα ἤδη ἡ ἀπὸ τούτου κίνησις ποίησις καλεῖται, ἡ ἐπὶ τὸ ὑγιαίνειν. ὥστε συμβαίνει τρόπον τινὰ τὴν ὑγίειαν ἐξ ὑγιείας γίγνεσθαι καὶ τὴν οἰκίαν ἐξ οἰκίας, τῆς ἄνευ ὕλης τὴν ἔχουσαν ὕλην …

And the healthy comes about from him thinking in this way: since such-and-such is health, it is necessary that, if there will be health, so-and-so must obtain, for instance homogeneity, and if this, heat: and so he keeps on thinking, until he brings (the thought process) to that which he himself has the power, in the end, to do (poiein). Then the movement away from this point is called poiēsis, poiēsis toward becoming healthy. So it follows in a certain way that health comes about from health, and a house from a house; out of that without matter, that which has matter.

Figure 5

In the Introduction, this passage was used to help imagine the opening of the Iliad, the bard’s movement from thought to action when bodying forth Chryses (in another speech, please note, protesting the abduction of a woman).

Aristotle’s process (see Figure 5) is a smooth cycle, but the Iliad uses a similar schema both for the Litai and for Phoenix’s speech as a whole to enact the entrance of a new, disturbing force. The Litai move from representation to action, being activated and “becoming themselves” via the disturbance of refusal and suddenly speaking vengeful prayers on their own behalf (see Figure 4). Phoenix thinks to calm Achilles’ thumos by using a canned story, but instead, via a central moment, provokes a force within that story to spring to life through himself.

Phoenix in Iliad 23: Another Ring

The ring structure itself may suggest a cosmology of eternal return, or it could suggest ending and renewal. We can but look to observe whether the concluding mood is hopeful or grim. The point is that the rhetorical form does not impose any particular mood for the ending. The general impression is that the ring is a literary form that is good for reflecting on, and for establishing a long view.

Mary Douglas, Thinking in Circles, p. 41

The other significant [1] appearance of Phoenix in the Iliad is at the funeral games for Patroklos in Book 23. Achilles stations him at the turning-point of the chariot race “to remember the courses, and report back the truth”:

σήμηνε δὲ τέρματ’ Ἀχιλλεὺς

τηλόθεν ἐν λείῳ πεδίῳ· παρὰ δὲ σκοπὸν εἷσεν

360 ἀντίθεον Φοίνικα ὀπάονα πατρὸς ἑοῖο,

ὡς μεμνέῳτο δρόμους καὶ ἀληθείην ἀποείποι.

And Achilles marked out the end-point

far off on the smooth plain: and near it he seated as a lookout

godlike Phoenix, companion of his own father,

so he could remember the courses and report back the truth.

τηλόθεν ἐν λείῳ πεδίῳ· παρὰ δὲ σκοπὸν εἷσεν

360 ἀντίθεον Φοίνικα ὀπάονα πατρὸς ἑοῖο,

ὡς μεμνέῳτο δρόμους καὶ ἀληθείην ἀποείποι.

And Achilles marked out the end-point

far off on the smooth plain: and near it he seated as a lookout

godlike Phoenix, companion of his own father,

so he could remember the courses and report back the truth.

Iliad 23.358–361

Phoenix is positioned at the midpoint as lookout or judge (skopos), yet he will not be called upon to render judgment after the race and instead vanishes from the poem. [2] This is odd, because his judgment is precisely what is needed in the ensuing dispute between Menelaos and Antilokhos. Instead, Achilles himself judges each event, rendering Phoenix superfluous. Why then does Phoenix appear in the games at all? As discussed above, it is likely that he had a traditional role in the Funeral Games for Achilles (as he did in lamenting Achilles), so to the extent that those games served as a model for these, [3] his appearance would be expected. Yet his role here in Book 23 turns out to be tailored to crystallize his speech in Book 9, much as the Litai mapped it out in advance.

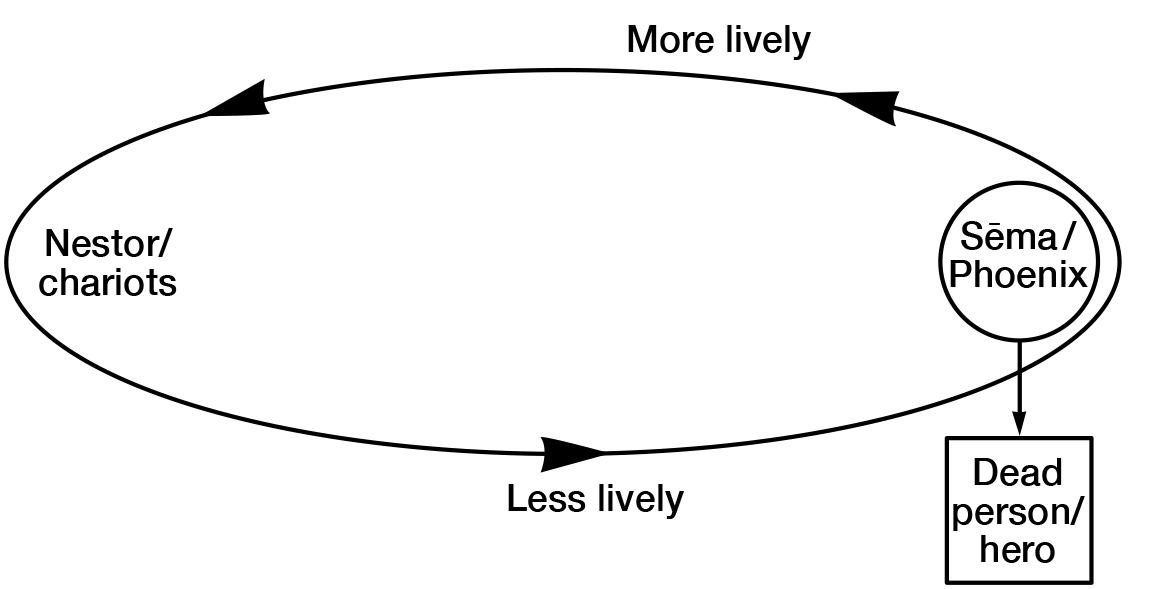

The chariot race is nearly overshadowed by the famous speech that precedes it, Nestor’s advice to his son Antilokhos (23.306–348). The speech’s ring composition itself embodies a chariot race. [4] It is abstracted in time and place up to the center of the ring, the elaborate description of the turning-post, and then moves into the concrete. In the first half, Nestor is pessimistic; then, as if gaining momentum from coming out of the turn, he suddenly becomes wildly hopeful about Antilokhos’ chances, “even if the others had Arion!” The turning-post, sēma, animates Nestor even though he is only going around it in speech. As we have seen, Phoenix’s rendition of the Meleager story is a masterpiece of ring composition, with the mise en abyme of Marpessa at its center and the speech of Kleopatra as its eerie culmination. Phoenix was identifying with and speaking as a dead heroine.

What stands as the midpoint of the chariot race, where Phoenix is stationed as a skopos, is itself a sēma, both a generalized marker (23.326) and a tomb (23.331). Nagy [5] brings out the significance of sēma and noos in Nestor’s speech and in the race itself, and connects this with the fact that “the turning points of chariot racecourses at the pan-Hellenic Games were conventionally identified with the tombs of heroes.” [6] In one instance, Taraxippos, “upsetter of horses,” was thought to be active from his tomb. [7] The chariot race is an ideal model for ring-composition, for disturbance by dead heroes at the center is precisely what we found in Phoenix’s speech.

There is another “phoenix” present at the chariot race, and this one helps interpret the other. As the racers are coming down the home stretch, one horse emerges as the leader: the phoenix horse with the moonlike white sēma on its forehead:

ὃς τὸ μὲν ἄλλο τόσον φοῖνιξ ἦν, ἐν δὲ μετώπῳ

λευκὸν σῆμα τέτυκτο περίτροχον ἠΰτε μήνη.

who for the rest of him was phoenix, but on his forehead

was rendered a white sign (sēma), peritrochos [round; revolving] like the moon.

λευκὸν σῆμα τέτυκτο περίτροχον ἠΰτε μήνη.

who for the rest of him was phoenix, but on his forehead

was rendered a white sign (sēma), peritrochos [round; revolving] like the moon.

Iliad 23.454–455

The Homeric use of phoenix in the adjectival sense “reddish” to refer to the dye [8] or the tree, is limited to this one line. The phoenix horse rounding the turn is similar to, or duplicates in miniature, the neighboring scene at the turning-post: Phoenix stationed by a sēma. The word περίτροχος (Homeric hapax) used to describe the white sēma on the horse recalls the sēma at the turning point. LSJ offers only “circular,” but the verbs περιτρέχω and περιτροχάω mean basically “run around,” and if περίτροχος is used of the sun and moon and of a hat, it bears both “running around” and “circular” meanings. On vase paintings of chariots racing around tombs—in particular, Achilles dragging Hektor around Patroklos’ tomb—the tomb is sometimes portrayed as a white, egg-shaped object protruding from the ground. [9]

What is the significance of this phoenix horse with its white sēma like the moon? This conjunction of the moon and phoenix brings to mind phoenix’s associations with the sun: that is, the solar phoenix-bird, who returns from the East at the end of an era to retrieve or replace his dead father (or to resurrect himself from his own ashes). [10] This link turns out to have broad implications.

In the immediate context, the link sheds light on the drawn-out contest over who can discern the first appearance of the leading horse. Idomeneus, at the sight of that horse, asks if he is the only one to αὐγάζομαι the horses (23.458), sparking a drawn-out dispute with Ajax son of Oileus. Richardson notes that this is the only occurrence of this verb in Homer, and cites West’s remark on Works and Days 478: “I suppose the essential idea is ‘fix the gaze on’ a particular object.” [11] But this rare verb, almost entirely poetic, cannot but recall αὐγή, a ray of the sun, in line with the solar imagery. [12]

Spotting the return of the sun is entirely appropriate in the context of a phoenix-bird. And the chariot race itself has solar connotations. The sun, of course, was thought to travel in a chariot, and the sun’s daily return from the underworld was linked with chariot racing around a tomb, and with human beings “returning to light and life.” This is succinctly illustrated by Pindar, Nemean 7.19–20, ἀφνεὸς πενιχρός τε θανάτου παρά σᾶμα νέονται, “Both rich and poor return by going past the sēma of death.” [13]

The same motif of return to life around the turning-point of a racecourse appears in the second stasimon of Euripides’ Herakles 655–662, when the old men wish that excellence would be compensated by a “double youth,” whereby after death virtuous men would run “a double course [δισσοὺς διαύλους] back to the rays of the sun.” [14] This “double course” would be, according to the chorus, a “clear sign of excellence” (φανερὸν χαρακτῆρ’ ἀρετᾶς, 659) by which one could recognize the bad and the good (665–666); but, they continue, “now, there is no clear boundary-marker [ὅρος] from the gods for the good and the bad, but a lifetime, whirling around [εἱλισσόμενος], builds up wealth only” (669–672). Martin notes that the “highly marked verb” ἑλίσσω is connected with a boundary-marker in the chariot race in Book 23 (line 309; to which add 466) as well. But the two passages also share an emphasis (indeed, a strange emphasis) on a clear sign that distinguishes one man from another as they come whirling around the turn. [15]

The race in Book 23 does not only exemplify the connection between cha-riot racing and the chariot of the sun. Rather it is exceptionally infused with imagery and diction associated with the sun and the sun’s “return,” with its connotations of rejuvenation and reanimation [16] —quite apart from the phoenix-bird. So it should not be surprising to find a further instance of solar imagery. The chariot race is introduced with a speech from Nestor to his son guiding him through the race. The very name “Nestor,” according to Frame’s analysis linking it to IE *nes-, cognate with nostos, has the significance of “bringing back to light and life.” Frame places Nestor in the context of solar imagery, or solar cult, [17] such that, for example, Nestor’s story of his cattle raid (Iliad 11.671–707) would go back to a story about retrieving the cattle of the sun, and “Pylos” would recall the gates of the sun at the edge of the world. [18]

The verbal root *nes- occurs also in noos, mind. Frame sees “return to light and life” and “mind” as deeply connected in a pattern repeated in the Iliad and Odyssey. The fruit of this connection is seen most clearly in the journey of Parmenides, which is both drawn (“escorted,” πέμπον) by horses and taking place in Parmenides’ mind. Nestor himself is strongly associated with νόος/νοέω throughout the Iliad, especially in the present passage. Given Nestor’s significance, and the chariot race’s associations with the sun, the phoenix-bird is quite at home in this passage.

Other details support a “return to light and life” interpretation of the race. Aside from the tomb itself, representing a “death” from which the heroes return (to Nes-tor), there is a repeated emphasis on it as the termata (309, 323, 333, 358). Nestor is said to have “told the peirata [limits] of each thing” to his son (350). The race is concerned with ends and limits.

The chariot race, moreover, like the other funeral games narrated in Book 23, draws upon the traditional stories of the returns (nostoi) of the heroes from Troy (and the fates of those who do not make it home), [19] just as its counterpoint in Whitman’s ring-compositional scheme, Book 2, echoed the war’s beginnings. Within this “nostos” frame or subtext, Nestor in instructing Antilokhos would be reenacting his role as one who returns the people to light and life, from the peirata and the termata embodied by the tomb; their salvation would be seen in the celestial horse driven by the winner.

Yet Antilokhos will not return at all, but will meet his death while saving his father, Nestor himself. Nestor’s instructions to his son about “limits” take on eerie overtones fully at home in Book 23. [20] Antilokhos’ death in the Aethiopis at the hands of Memnon will bring on Achilles’ own actual death in avenging him, as Patroklos, in Achilles’ armor, has brought on Achilles’ metaphorical death in the Iliad. Antilokhos is in short Achilles’ Patroklos-replacement, [21] a relationship mentioned in the Odyssey. [22] At the end of the chariot race, Antilokhos refuses to give his prize to Menelaos, in a line rich with resonance (23.552). τὴν δ’ ἐγὼ οὐ δώσω, “her [the mare] I will not give up,” he says, and let someone try me, whoever wants to fight me with his hands. The speech recalls Agamemnon’s refusal to hand over Chryseis, τὴν δ’ ἐγὼ οὐ λύσω (“her I shall not release,” 1.29), which instigated the plot of the Iliad by replaying the stealing of a female. [23] Poor Menelaos is again on the point of replaying the loss of a female (here, a mare rather than a woman) to a beautiful youth, [24] but for the intervention of Achilles.

Antilokhos’ words recall also Achilles’ own threatening words at 1.298–303. Achilles’ response to Antilokhos’ threat here in Book 23 is to smile, “delighting in Antilokhos, because he was his dear companion (hetairos)” (23.555–556). Richardson, noting that this is the only time Achilles smiles, remarks that Achilles “knows … what it means to be deprived of one’s prize” and takes the passage to be a “a sign that they both share the same nobility of character.” [25] No: the smile is another eerie recognition of Antilokhos’ future role, replacing Patroklos as Achilles’ “dear companion,” and, like Patroklos, dying. The authorial, unrattled Achilles smiles just as the authorial Zeus smiles upon awakening (15.47) and issuing his long speech calmly “predicting” the tragic remainder of the Iliad, including the death of Patroklos. All this results in a chain-reaction exchange of prizes whereby all are satisfied. Another Iliad is averted, but an Aethiopis, with the death of Achilles, is set in motion. Antilokhos’ death, then, is at stake in Book 23, layered atop Patroklos’ funeral.

So the chariot race in itself is infused with imagery of return to life and light, given its odd vocabulary, the speech of Nestor, the undercurrent of nostos stories. But Nestor, as we began to see, is not the only solar figure here.

The phoenix-bird has further features in common with the Phoenix/phoenix under consideration. The early literary evidence is scanty, [26] but it is clear that the Hesiodic tradition alluded to the phoenix as a familiar theme. While the preponderance of artistic depictions of the bird appears much later, in a Christian context, the phoenix was clearly better known to Greeks of the archaic and classical periods than the extant number of allusions would suggest. We cannot say which features of the bird were familiar at a given stage of the Iliad’s development, but several are fundamental. The phoenix-bird is a fabulously long-lived creature associated with the sun. He is born from the ashes of his predecessor or otherwise comes to replace him at his death, or else regenerates himself at his own death. At any given time, there is only one. The lifespan of the phoenix is associated with various astronomical systems and cycles. His long life was already proverbial for Hesiod; he appears in a riddle with various creatures whose lifespans are multiples of one another and of human beings. [27] According to Herodotus (2.73), he appears at Heliopolis once every five hundred years, when his father dies. Thus, the phoenix-bird, like Nestor (Iliad 1.250–252, Odyssey 3.245–246), [28] lives a certain number of “generations of men.”

Besides being associated with a return/resurrection at the end of a long era, the phoenix-bird is also pictured as the escort of the sun in its daily course to the underworld and back. [29]

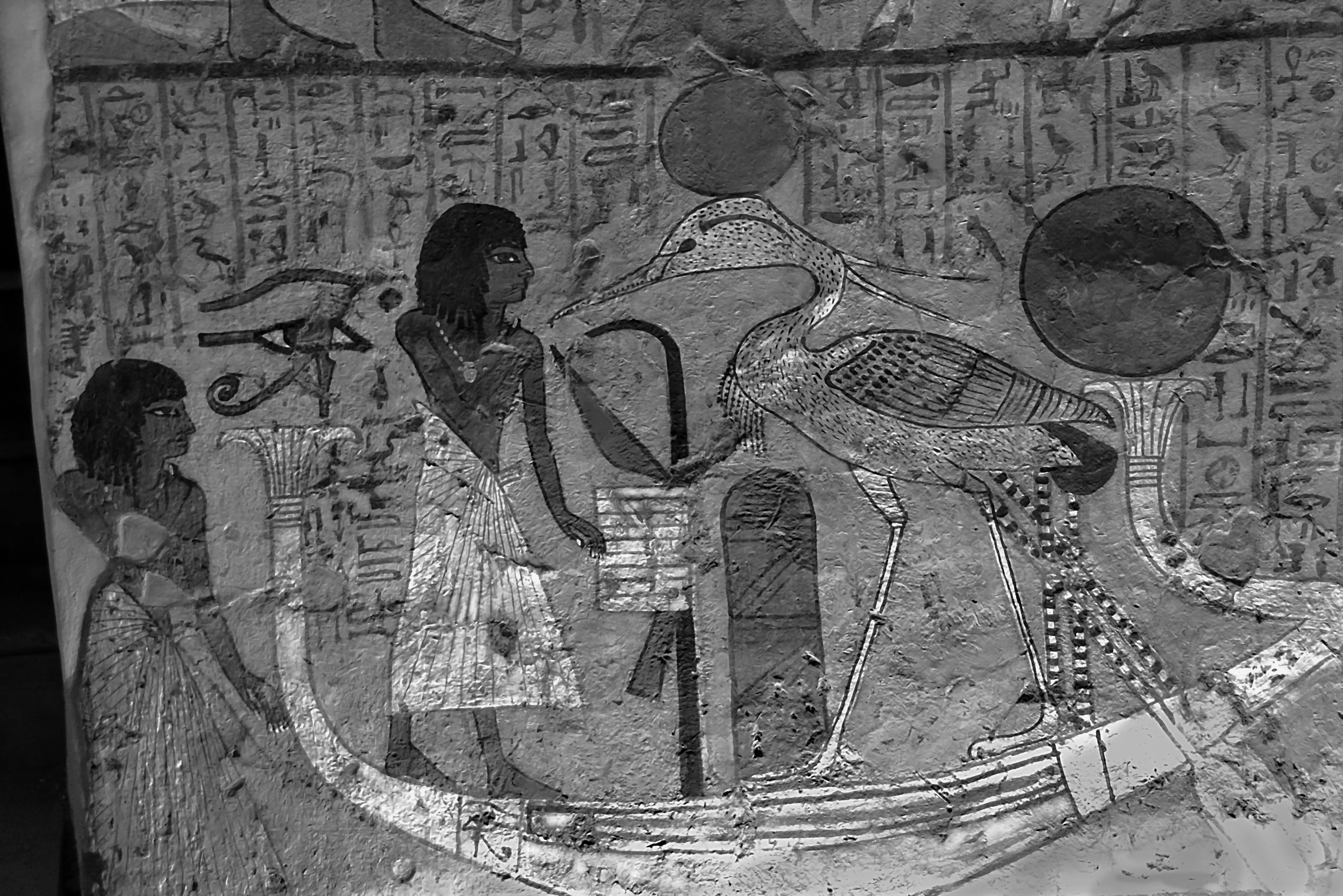

Figure 6

The Egyptian solar bird benu, with a solar disk over his head, is probably the same Egyptian bird mentioned by Herodotus, [30] which he says is the “phoenix.” The benu accompanies the dead on their journey to the afterlife, for instance, in the barge of the sun (see Figure 6). [31] The bird is pictured standing on or next to tombs [32] or on an upright mummy. [33] It is tempting to link this quality to Phoenix stationed by the tomb. In the last mentioned example, admittedly a late and unusual one, on a mural painting in the temple of Isis in Pompeii, the bird’s head bears a uraeus with a solar disk and a lunar crescent.

The phoenix-bird, like the sun itself, is an overseer of human beings: [34] a judge like Phoenix, the skopos who is to report back the truth about the dromoi. [35] The sun is the skopos par excellence: Demeter addresses Helios as θεῶν σκοπὸν ἠδὲ καὶ ἀνδρῶν (Homeric Hymn to Demeter 62), standing in front of his horses. The phoenix as escort of the chariot of the sun is akin to the chariot race in general and the phoenix horse in particular. At the Eastern extreme, the phoenix is reborn on his own tomb, nest, or pyre, or his father’s egg. This self-reanimation differs from rescue by a solar hero/deity (cf. Frame on Nes-tor), but the similarity is clear.

Enough has been said to make plausible an association between Phoenix standing by the sēma, the phoenix horse with its moon sēma, [36] and the phoenix-bird. It is best not to limit the harmonic resonances, but here are some interpretive paths:

Connections with Phoenix’s speech in Book 9 present themselves. Even Phoenix’s remark at 9.445, “Not even if the god himself should promise / to smooth away my old age and set me back in blooming youth,” looks different. Griffin [38] believes these lines to be the source of the lines in the Nostoi (fr. 6) where Medea (herself of solar descent) magically rejuvenates the elderly Aeson.

1. Phoenix, at the turning point (cf. τροπαὶ Ἠελίοιο, the solstice point; see below Chapter 4), which is a tomb, like the phoenix-bird perched on the tomb, now returns—like the sun (cf. αὐγάζομαι) from solstice or from the underworld. [37]

2. The subtext of Book 23 being the Returns (nostoi) of the heroes, Phoenix turns into a horse as escort of heroes back home, just as the phoenix-bird escorts his dead father (cf. Herodotus) or the sun itself. Phoenix here is a (transitive) returner of heroes (cf. Nestor) rather than (intransitive) the returning sun (cf. esp. Parmenides 1).

3. Taking more literally the moon sēma as an image, there is a movement from the indexical (sēma as marker) to the symbolic, or a movement from the more to the less bodily; Phoenix disappears from the poem into a phoenix horse that is hard to discern and has a distinguishing moon-spot (eclipse).

4. There is a conjunction or eclipse with some more enigmatic meaning.

Most conspicuous is the reference at the center of the Meleager story to the ἀλκυών, the halcyon bird. We noted that this was a timely myth at the middle of a ring composition, because it concerns the endpoint of the sun’s annual travels (winter solstice), when it stands still before returning to bring life back to the world. This annual cycle complements the sun’s nightly journey to the underworld, accompanied by the phoenix. On a still larger scale, the cosmos, through the phoenix, renews itself after a number of years. Thus both birds, the halcyon and the phoenix, achieve rebirth out of a deathly turning point (Hades/winter/pyre/tomb/corpse): the reemergence of the sun. [39]

This solar emergence at the center on the level of theme corresponded, then, to the ring structure with its central figure, embedded like a Russian doll, and compressed into a narrow space. Theme and structure (poiēsis) effected a “burst of energy” in the speaker, Phoenix. This “burst of energy” is often seen in ring composition, most notably in Nestor’s chariot race speech, whose muted, cautious first half swerves inexplicably into unbridled optimism in the home stretch, pivoting on the description of the turning point (see Figure 7, next page).

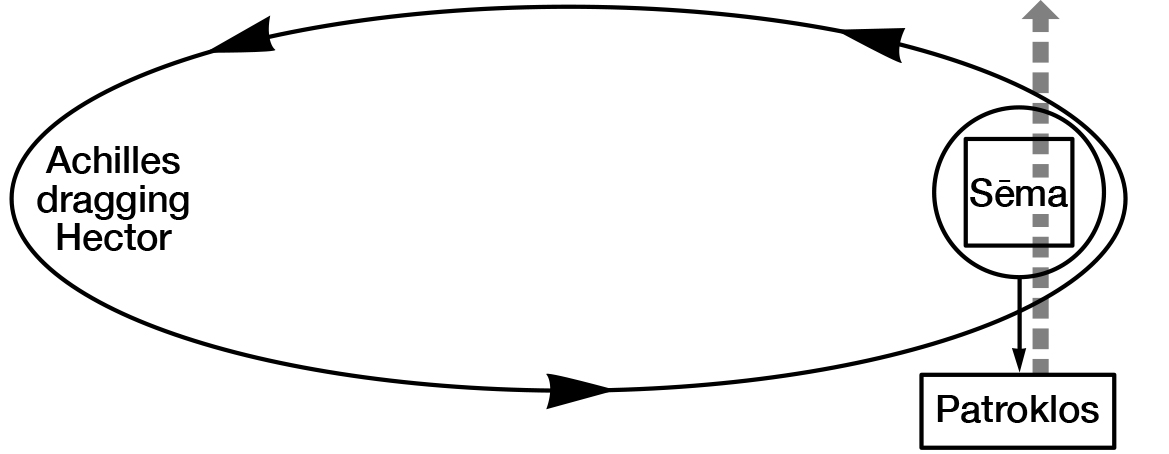

But the burst of energy in Phoenix’s speech was disturbing as well as enlivening, not so much the sun “disturbing” its course and coming back, as an angry hero rising from his tomb, like Taraxippos, to upset the rhetorical horses. This aspect of mourning and of hero cult is active in the poem. When Achilles drags Hektor around Patroklos’ tomb (24.14–18), it seems to be a vain effort to bring Patroklos back (see Figure 8). And in the well-known vase paintings depicting the scene, he does come back: Patroklos’ psyche flies out from his white, egg-shaped tomb, fully armed. [40]

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

In this scene, it is Patroklos. In Phoenix’s speech, it is his counterpart Kleopatra who is raised to the surface, fueled by her mother’s story at the center of the ring. [41] A combination of necromancy and memory brought Phoenix to the center and from there brought Kleopatra to the surface. Phoenix, like Parmenides and like Nestor (and Aristotle’s physician), went on a ring journey through his memory (see Figure 9). But it was Kleopatra’s memory, the stories in her phrēn, that raised her to the surface for her speech and that roused Meleager from his bed. Kleopatra finally threw Phoenix’s rhetoric off course.

Phoenix, like a bard, acted to “escort” dead heroes into the space of performance and back to life. (Another escort of heroes who resurrects them and is connected with the phoenix is Nausikaa, whom Odysseus compares to the phoenix [palm] on Delos [Odyssey 6.162–163] [42] and who, he says, “lifed” him [8.468] during his sojourn with the otherworldly escorts the Phaeacians.) Phoenix’s position in Book 23 at the tomb and his duty to “remember the courses and report back the truth” (ὡς μεμνέῳτο δρόμους καὶ ἀληθείην ἀποείποι) recalls his necromantic memory-work in Book 9. This emphasis on memory dovetails with the link between noos and nostos as explicated by Frame. The tomb’s obvious memorial function is played upon when Nestor tells Antilokhos that the man with slower horses turns around the termata keeping his eyes on it, nor does it escape (λήθει, 23.323) him, and proceeds to reveal the nature of the turning-point as a tomb, saying first “I shall give you an exact sign (σῆμα), and it shall not escape you (λήσει)” (23.326). In fact the only other instance of the word “truth” (ἀληθείη) in the Iliad (24.407) is when Priam is asking the disguised psychopomp Hermes for the truth about his dead son’s corpse.

With these connections in mind, let us turn again to Marpessa, Kleopatra’s mother. Marpessa’s father Euenos (“well-reined”) defeated her suitors one by one in deadly chariot races. His name closely resembles Euenios, the name belonging to a figure Herodotus (9.92.2–95) describes as a prophet and guardian of solar sheep, as Geryon or the Sun’s daughters guard the solar cattle. [43]

Once we go down that path, we are not dismayed to find that Idas, who rescues Marpessa from Apollo, is known as a raider of cattle and also that he and his brother Lynkeus are cousins of the Dioskouroi, the Divine Twins. [44] It is Idas and Lynkeus who kill Kastor and present Polydeukes with the choice of sacrificing half of his immortality to bring Kastor back to life. Idas and Lynkeus (the Apharidae) are also objects of cult (Pausanias 4.27.6).

The prophetic nature of Phoenix’s speech in Book 9 is in keeping with the solar imagery. [45] He selects a paradeigma that mirrors what has gone on so far (the embassy: the first two parties in the sequence of suppliants to Meleager), but goes beyond it, planting the seed of the tragic Patroklos plot. In this he is similar to Circe [46] in the Odyssey, a prophetic solar figure wrapped up in ring composition (cf. her name). As the solar Circe gives Odysseus guidance as to how to get safely out of the underworld, Phoenix is attempting to get Achilles out—and his tent, at least by Book 24, is a kind of underworld. We will examine further evidence for the return of Achilles as a reanimation in the next chapter.

Given all this, it is surprising that no extant ancient commentator tells us all about a relationship between Phoenix and the phoenix-bird, and of those two with Nestor. Then again, perhaps the Phoenix/Nestor/chariot/sun complex is a relic, lingering from a tradition—only in the case of Phoenix, not an Indo-European one! On such a reading, the individual elements, like the lines about “escaping from death” in the Odyssey, would remain despite their having been unmoored from the original sun-worship context. [47] But the phoenix-bird is most certainly not a relic, but a living tradition; and there is other evidence that we must now consider.

Phoenix in Visual Art

Although no ancient writer does so, ancient wall painting may preserve further evidence for an interpretation of Phoenix along the lines sketched in the previous pages. If this evidence is deemed relevant, it would bolster the idea that the symbolic complex under discussion is not merely a relic. Any attempt to relate the artistic evidence to the previous discussion is fraught with problems, and certainly stretches beyond the bounds of my expertise. But after I had analyzed the Phoenix speech and his role in Book 23, two specimens of ancient wall painting seemed to offer visual correlations to some of my analysis. I pivot out here into visual art to stimulate readers to think in three dimensions. It could be that some ancient listeners (and spectators) were better attuned to the spatial aspect of Phoenix in the Iliad and its broader tradition, in the way I have discussed, and that this found rich expression in the way they decorated their surroundings. [48]

Figure 10

Nestor and Phoenix are depicted mirroring or facing one another in various visual media. [49] This is no surprise: they are obviously similar characters, apart from any particular “return” or “sun” significance, and apart from their roles in the chariot race. Nevertheless a few visual examples do point toward this particular complex of symbols.

In some of the examples where Nestor and Phoenix are paired, they are observing the funeral games of Patroklos: most notably, the sacrifice of Trojan prisoners upon the tomb of Patroklos. For example, on a volute crater from Canosa from about 340/330 BCE, [50] they are hovering over the sacrifice observing it from the upper tier of a three-tiered vase painting, and turn to one another to discuss the matter. Although the two are set apart in their own tent-like space, they share this upper register with several gods.

Figure 11

The François Tomb, an Etruscan tomb whose frescoes date from 330–310 BCE, roughly the same date as the volute crater, is a tomb of extraordinary proportions with an elaborate decorative program (see Figure 10). [51] Once again Phoenix and Nestor (named in the inscriptions) face one another, this time on opposite sides of a door to one of the burial chambers (see Figure 11).

Behind each figure a large palm seems as though it is growing from each head. Here too, moreover, the sacrifice of Trojans occupies a significant place in the tomb. The sacrifice is depicted along a wall leading up to the focal door of the entire tomb, opposite another wall depicting an important event from Etruscan history, portraying it as an event akin to the sacrifice of prisoners.

This is part of an elaborate system of mirrors in the tomb’s decoration. Phoenix and Nestor face each other beside the door to Chamber 9, while two other figures face each other beside the door to Chamber 5 on the other side of the atrium. Directly across from Nestor is a figure labeled “Vel Saties,” presumably a historical figure, and perhaps the inhabitant of Chamber 5. [52] Vel Saties stands next to a small figure, a child or a dwarf, who is holding a bird. Some scholars interpret this small figure as performing haruspicy. Unfortunately, the figure directly across the atrium from Phoenix has been lost; but here, as with the Trojan prisoners and the Etruscan slaughter, characters from the Iliad are set opposite actual Etruscans. And not just any Iliad characters, but ones traditionally associated, in the poem and in visual art, with Book 23’s funeral games and, in art, with the sacrifice of Trojan prisoners.

What then is the significance of the two elderly Achaeans facing the two dead Etruscan inhabitants of the tomb? One interpretation is that “Phoenix” is an eponymous figure of the Phoenicians, while Nestor represents the ancestor or founder-figure of the Etruscans. In support of this interpretation, Coarelli speculates that the palm (phoenix) behind Phoenix is a sign that Phoenix is simply an eponym of the Phoenicians or more particularly, since they had close ties to the Etruscans, the Carthaginians. [53] Nestor would then be the ancestor of Vel Saties, while Phoenix would be an ancestor of the putative Carthaginian pictured facing him. In objection to this it is pointed out [54] that both Phoenix and Nestor have palms [55] behind their heads. At any rate, the two appear in the vicinity of the sacrifice of Trojan prisoners, in accord with the tradition linking the two elders with the sacrifice.

Unlike in the other examples, Phoenix and Nestor do not observe or preside over the sacrifice of Trojans, which is nevertheless depicted around the corner. What are they doing here opposite Vel Saties and his cryptic companion? If Vel Saties represents the family buried in this tomb, his position opposite Phoenix and Nestor suggests that, rather than simply mirroring him, they are escorting him into the afterlife or otherwise mediating, like the Etruscan Underworld figures seen among the Trojan captives, the tomb-dwellers’ dealings with death. [56] It is admittedly puzzling for this interpretation that Phoenix and Nestor are not either heraldically surrounding the door of Chamber 7, the visual focal point of the tomb, or surrounding the entrance to the tomb, the doorway leading from the “tablinum” into the atrium. Nevertheless, the François Tomb and the chariot race in the funeral games of Book 23 seem to ask to be read together somehow, rather than Phoenix and Nestor serving as more generic figures of wisdom. It would admittedly be easier to do so if they flanked the door of Chamber 7, which might be thought of as the central tomb (sēma) seen from the dromos. Still, they do occupy such a “turning-point” position vis-à-vis Vel Saties and his companion.

The door near Vel Saties originally bore a painting that disintegrated while being transported. Art historians note the strong symbolism of the door and of the “epiphanic” quality of the figure on it. [57] The figure on this door is thought to have been female. Perhaps then Vel Saties had a portrait of himself placed next to the door to his wife’s chamber, on the door of which she was painted. Thus the door was both the site where she crossed into death and where she appeared in an epiphany after her death.

Both because of the fragmentary nature of the evidence and because the tomb’s paintings seem designed to be suggestive, a simple, totalizing reading is not attractive. What has emerged, however, is a relationship between Phoenix and Nestor and the inhabitants of the tomb, and a relationship to the tomb itself as a liminal space. If one thinks of the painted figure on Chamber 5 as beginning a loop roughly like the chariot race, [58] Phoenix and Nestor would preside over the midpoint, at which there was, indeed, a tomb. If the painted figure instead provides the turning point, Phoenix and Nestor would stand at the beginning and end of that race. Unfortunately for this latter interpretation, the two should be switched so that Nestor could guide the beginning and Phoenix judge the end (assuming a counterclockwise race as in the Iliad). Perhaps Vel Saties reserved Chamber 9 for himself, so that he and his wife could visit one another in this reciprocal fashion, while being painted next to one another as well.

At any rate, however we interpret the details, the François Tomb appears to indicate that the associations between Nes-tor and “rescue from death,” [59] as well as a strong association between Phoenix and Nestor and of the pair to the funeral games, remained alive among the Etruscans of the late fourth century, Iliad connoisseurs with a voracious appetite for elegant visual art inspired by it and by associated traditions.

There is another exceptionally large-scale work that merits attention in this regard. This work is manifestly concerned with the structure of the Iliad, and highlights the chariot race in the games for Patroklos. The House of Octavius Quartius (Pompeii II.2.2) is an opulent house with an enormous garden, stretching out over nearly the whole of Insula II.2 (see Figure 12). [60] The triclinium (or oecus) is strategically oriented toward the garden, which stretches out from its south door. The two primary friezes in this room depict episodes from the Herakles cycle (the upper frieze) and the Iliad (the lower frieze). The lower, smaller frieze begins to the west of the south door with Apollo, instigating with his arrows the plague of Iliad 1. Proceeding north, after a doorway, we have the Teichomachia, followed by the Battle at the Ships (Book 15: Ajax and Hektor are shown). Proceeding clockwise onto the north wall, there are some “Phrygians” (inscription), followed by Patroklos on the rampage with Achilles’ horses, trampling over corpses (Book 16). Following this is Thetis and Achilles with the Shield (Book 18) and a chariot guided by Automedon dragging the corpse of Hektor.

Turning the corner onto the East wall, the viewer sees a large expanse depicting the funeral games of Patroklos, the beginning of which is damaged. The chariot race takes up the most space here, followed by small figures of a discobolus and two boxers. Following this is Achilles supplicated by Priam, [61] and then two figures identified as “Priam and a Trojan, perhaps the herald Ideus.” [62] One would expect the episodes to end here or else proceed to the funeral of Hektor, but we have instead Achilles and Phoenix. [63] (I mentioned this vignette above because Phoenix is here kneeling before Achilles just as Priam had done two vignettes to the left.) Then follows a solitary pensive figure, presumably Achilles alone outside his tent. Turning the corner to the south wall, there is an embassy to Achilles. This is presumably the embassy of Book 9, but from what I can see it could also be the heralds dispatched in Book 1. In other words, the lower frieze depicts the principal events of the Iliad in order—except for the embassy, and in particular Phoenix and Achilles.

The larger, upper frieze depicts two sequences of events, both of which begin at the north wall and proceed south, ending at the garden doorway. The eastern sequence features the deeds of Herakles and Telamon. It proceeds from the rescue of Hesione through her restoration to her father Laomedon, Herakles killing Laomedon, the wedding of Hesione and Telamon presided over by Herakles, Herakles with a bow, and finally, Herakles investing the young Priam, brother of Hesione, with royal power. The western sequence depicts the events of Herakles’ death. Beginning from the north wall, Herakles fights Nessos; proceeding to the west wall Nessos gives Deianeira poison, Herakles on the pyre is assisted by Philoctetes, and finally, on the south wall, a very fragmentary image presumably [64] showed Herakles being escorted to Olympus. Thus whoever is sitting at the north end of the room is “embraced by the frieze of Hercules”—by these two sequences that culminate in the two scenes straddling the passage into the garden, scenes of mortals crossing into royal status, on the one side, and immortality, on the other: “two models of political-moral promotion supported by the current Stoic philosophy. The waterway that runs through the garden is placed along the axis of the South door of the oecus: the green and the water of the garden reward those who, having absorbed the moralistic lesson, pass from the darkness inside into the light outside.” [65] This passage from darkness into light is however quite literally undermined by the panel beneath. Most pointedly, the young Priam on the upper frieze on the south wall faces the corpse of Hektor being dragged on the lower frieze on the south wall, and is also in the neighborhood of his aged self ransoming his son’s body. The oecus has a tinge of the tragic sense that infused the François Tomb.

Figure 12

Why is Phoenix out of place in the otherwise chronological sequence? Keeping in mind the other evidence linking Phoenix and Nestor to the funeral games, it is tempting to think that Phoenix here occupies the would-be “turning-point” of the chariot race that dominates the wall to the left. [66] If so, Phoenix is doing several things at once. He is reprising Priam’s supplication just to his left, [67] while occupying spatially his position at the turning-point of the chariot race, and reprising his Book 9 role, supplicating Achilles to “go out of his chamber” toward (à la Meleager) his death.

In this richly stimulating room, Phoenix and Nestor do not, as they do in the François Tomb, flank the symbolically loaded doorway to the garden. Nevertheless, the Book 23 schema seems to be operating here too. Phoenix presides over the exit of Achilles toward his death in close proximity to the south exit to the garden, an exit that already, from the two sequences in the upper frieze, bears clear significance as a passage into blessedness, even immortality. Yet the garden on the other side is no generic Elysium (see Figure 13 [68] ).

Figure 13

The long, narrow garden is bisected by a channel, ending just before the south limit of the property in a circular fountain and a couple of planters (?). One who strolls in this garden walks south, turns around, and comes north again, returning into the oecus. Such a person is not only reaping the rewards of whatever Stoic lesson is on offer in the upper frieze; he or she also reenacts the chariot race depicted on the lower frieze.

What would one give to be a guest of the Homer enthusiast who commissioned this house, to dine in its triclinium and take in these scenes—surely this room hosted some form of Homeric performance—and afterward to stroll around the garden, pondering the painting? Here, spread out over the heads of the diners, would seem to be the performer’s very path of song, an ecphrasis in reverse, or a literalization of the performer’s mnemonic loci. If the circling Muses could serve Mnemosyne, why not seated diners—actual occupants of couches, rather than ones in the poem? [69] But the path here would seem to go astray: why did the host have Phoenix painted in this way? Does the host associate the south doorway with death? Was he aiming, at the endpoint of our feast and its stories, for a space in which we might feel ourselves to reenact them?

Conclusion: The Speech of Phoenix and Its Contexts

Phoenix’s appearance in the chariot race in Book 23 turns out to be closely attuned to his speech in Book 9. There is a surprising confluence among drama, structure, and theme: the importance at the speech’s center of a silent dead figure who is animated through the person of Phoenix in the second half of the ring, its dramatic change after this turn—as in the speech of Nestor guiding Antilokhos—as though something has changed in the mind of the speaker in tandem with that strange emergence of another figure. The themes associated with Nestor and Phoenix—solar cycles of day and year, solar birds, noos, the underworld, patricide (phoenix-bird), bursting out of gates—figured into Phoenix’s speech. These images, along with the imagery of containment/bursting out, imprisonment and rescue, were all related within a web embracing plot and imagery (poetics), on the one hand, and embodiment, instantiation and performance (presence), on the other. [70]

If the plots (poetics) of the Iliad and Odyssey are organized around the return from “death” of their respective heroes, there is a corresponding reanimation on the level of presence. We have seen one of the best examples of this in the script of Iliad 9, the speech of Phoenix, and we shall see further examples in the following chapters. The power of the script derives in part from themes and images, and especially the theme/gesture of cursing that culminates in the emergence of Kleopatra. This becoming, this ‘carnation’ of the character by the bard, belongs in the realm of the ‘reincarnation’ or rescue from death that goes on in noos/nostos. Epic acting takes its place within this reanimation.

In case all this seems too complex, perhaps that is only natural. It may be that to talk about Alkyone and Phoenix is to enter the realm of riddles. Above I mentioned that one of the only things known about the Wedding of Keux is that riddles were told. [71] And let us look again at the Euripides passage mentioned above, [72] sung by a chorus of captive Greek girls in the East, yearning to return west to Greece (cf. the nostoi of heroes in Book 23). Note the presence of Apollo and Artemis, and phoenix as palm; we return to this grouping in Chapter 4.

ὄρνις ἃ παρὰ πετρίνας

1090 πόντου δειράδας ἀλκυὼν

ἔλεγον οἶτον ἀείδεις,

εὐξύνετον ξυνετοῖς βοάν,

ὅτι πόσιν κελαδεῖς ἀεὶ μολπαῖς,

ἐγώ σοι παραβάλλομαι

1095 θρήνους, ἄπτερος ὄρνις,

ποθοῦσ’ Ἑλλάνων ἀγόρους,

ποθοῦσ’ Ἄρτεμιν λοχίαν

ἃ παρὰ Κύνθιον ὄχθον οἰ-

κεῖ ποίνικά θ’ ἁβροκόμαν

1100 δάφναν τ´ εὐερνέα καὶ

γλαυκᾶς θαλλὸν ἱερὸν ἐλαί-

ας, Λατοῦς ὠδῖνι φίλον,

λίμναν θ’ εἱλίσσουσαν ὕδωρ

κύκλιον ἔνθα κύκνος μελωι-

1105 δὸς Μούσας θεραπεύει.

Bird, you who along the rocky

ridges of the sea, halcyon,

sing your doom as a lament,

a cry easily intelligible to the intelligent,

that you croon to your husband in song for all time,

I set beside you

laments, I a wingless bird,

longing for the gatherings of Hellenes,

longing for Artemis of childbirth

who has her home by the Kynthian hill

and the phoenix, lavish-leaved

and the laurel, sprouting

and the sacred shoot of grey olive,

dear to the child of Leto’s pangs,

and the lake, whirling its water

in circles, where the swan, singing,

serves the Muses.

1090 πόντου δειράδας ἀλκυὼν

ἔλεγον οἶτον ἀείδεις,

εὐξύνετον ξυνετοῖς βοάν,

ὅτι πόσιν κελαδεῖς ἀεὶ μολπαῖς,

ἐγώ σοι παραβάλλομαι

1095 θρήνους, ἄπτερος ὄρνις,

ποθοῦσ’ Ἑλλάνων ἀγόρους,

ποθοῦσ’ Ἄρτεμιν λοχίαν

ἃ παρὰ Κύνθιον ὄχθον οἰ-

κεῖ ποίνικά θ’ ἁβροκόμαν

1100 δάφναν τ´ εὐερνέα καὶ

γλαυκᾶς θαλλὸν ἱερὸν ἐλαί-

ας, Λατοῦς ὠδῖνι φίλον,

λίμναν θ’ εἱλίσσουσαν ὕδωρ

κύκλιον ἔνθα κύκνος μελωι-

1105 δὸς Μούσας θεραπεύει.

Bird, you who along the rocky

ridges of the sea, halcyon,

sing your doom as a lament,

a cry easily intelligible to the intelligent,

that you croon to your husband in song for all time,

I set beside you

laments, I a wingless bird,

longing for the gatherings of Hellenes,

longing for Artemis of childbirth

who has her home by the Kynthian hill

and the phoenix, lavish-leaved

and the laurel, sprouting

and the sacred shoot of grey olive,

dear to the child of Leto’s pangs,

and the lake, whirling its water

in circles, where the swan, singing,

serves the Muses.

Euripides, Iphigenia in Tauris 1089–1105

Figure 14

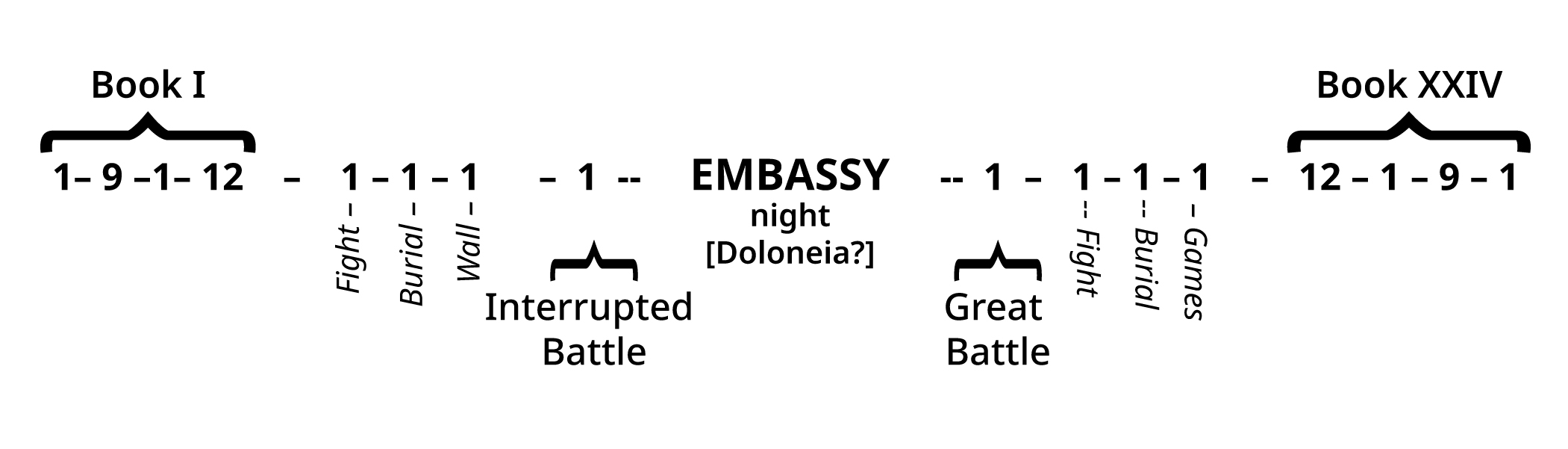

One last piece of evidence ties Phoenix’s speech to a solar-lunar cycle that is also ring-compositional: the location of the speech in the poem, in the exact chronological center.

The calendar of the poem (Figure 14, after Whitman 1958:257) is carefully set out in a symmetrical scheme. This symmetry is centered on a different point from that in Whitman’s ring-composition map of the poem by theme, but is just as striking. This calendar reflects the poem’s accounting in multiples of 3 and 9, [73] but also ensures that there is a month preceding and following the night of the Embassy. As a result, the Embassy may be thought of as occurring during the same phase of the moon as the beginning and end of the poem, as a new moon or full moon. This would accord with the phoenix horse and his moon, and bring the Iliad into line with the Odyssey’s solar and lunar cycles. [74] The main point is that Book 9 is at the center of the calendrical ring, flanked by four days before and after it, days which themselves form a ring within the ring. [75] “All the meaning is to be found there.” [76]

Figure 15

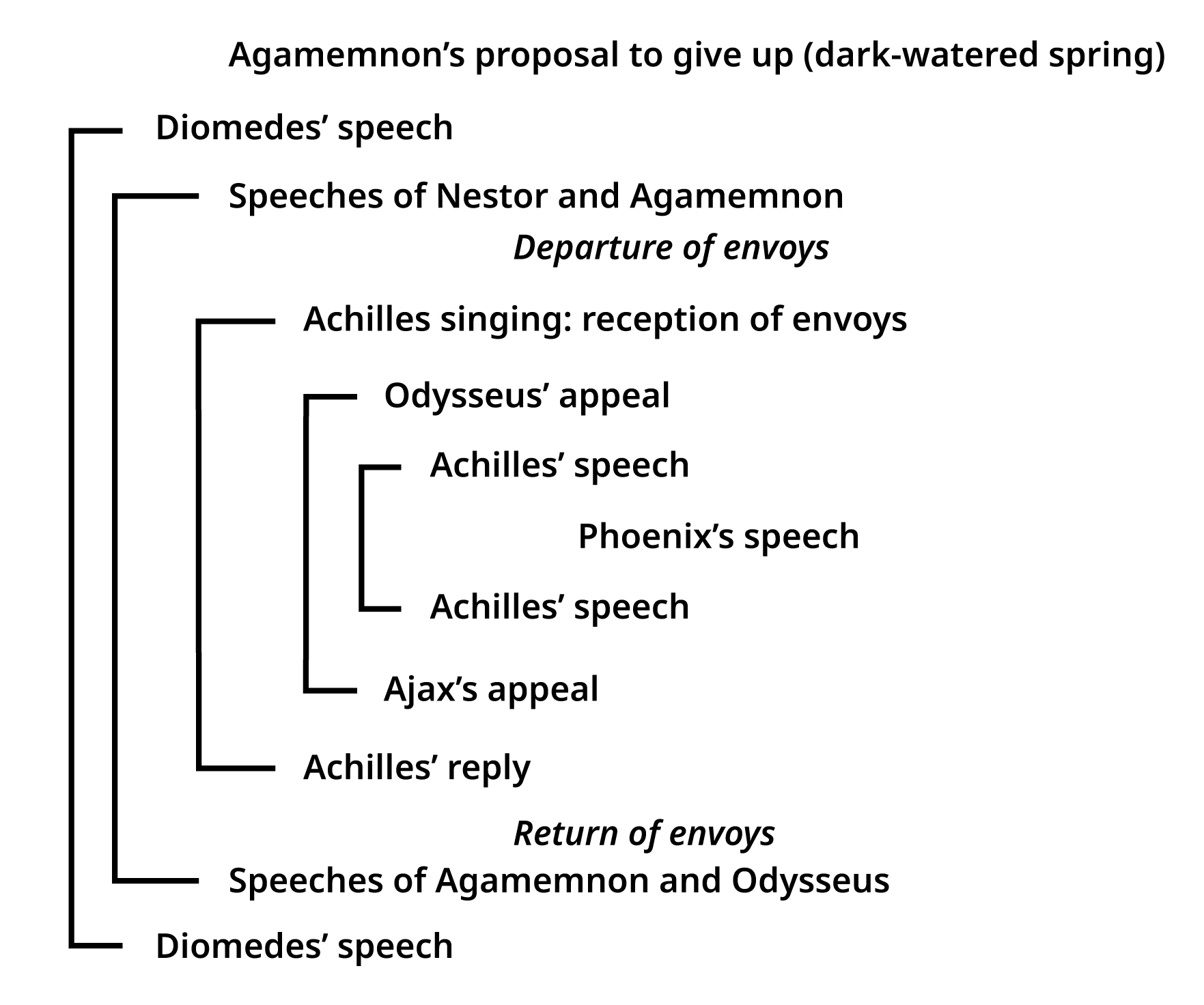

Within Book 9, Phoenix’s speech occupies the central position, as Whitman’s better-known chart shows (see Figure 15, adapted from Whitman [77] ).

Phoenix’s speech is, as we saw, divided into three panels: the autobiography, the Litai, and the Meleager story. Within the Meleager story (not the central panel), there are three sections. In the central section, Meleager is embedded in the recesses of his house with Kleopatra. And within that central section, pointedly ensconced in the center of ring composition, was the story of Kleopatra’s mother Marpessa.

I. The War of the Kouretes and the Aetolians. 524–549

II. Meleager Retires from the Battle. 550–574

A The Battle Rages. 550–552

B Meleager’s Wrath. 553–555 χόλος

C He Retires with Kleopatra. 556 κεῖτο

X Kleopatra ’ s Mother. 557–564

C′ He Retires with Kleopatra. 565 παρκατέλεκτο

B′ Meleager’s Wrath. 565–572 χόλον

A′ The Battle Rages. 573–574

III. Meleager Is Persuaded. 574–599. (Catalogue of suppliants.)

II. Meleager Retires from the Battle. 550–574

A The Battle Rages. 550–552

B Meleager’s Wrath. 553–555 χόλος

C He Retires with Kleopatra. 556 κεῖτο

X Kleopatra ’ s Mother. 557–564

C′ He Retires with Kleopatra. 565 παρκατέλεκτο

B′ Meleager’s Wrath. 565–572 χόλον

A′ The Battle Rages. 573–574

III. Meleager Is Persuaded. 574–599. (Catalogue of suppliants.)

The allusion to Alkyone was vital to understanding the speech as a whole. This triple- or quadruple-embedding in ring composition (a ring-composition largely built upon numbers of days, and day-and-night alternations) strengthens the links between Alkyone and Phoenix and their solar associations. Recall, finally, that the myth of Alkyone is a myth not about a single point in time, but about a series of days straddling the winter solstice. There is a poetics of the nightingale in Homer; but there is also a poetics of the halcyon. [78]

The next chapter uncovers an instance of emergence at the center at the geographical turning point rather than the chronological center of the poem. At the end of Book 15, the Trojans finally reach the Achaean wall and threaten to burn their ships, as is contemplated in the speeches in Book 9 and imagined in the fire raining down on Meleager’s chamber. The disaster imagined via the Meleager story is finally happening. While the plot features the reemergence of the Patroklos-Achilles pair (followed by the aristeia and death of Patroklos), this is coupled with the emergence of yet another dead hero and his wife. Once again, a performative (presence) uncanniness is built atop an uncanny thematic (poetics) foundation: this time not an act of cursing but a return from death.

Footnotes

[ back ] 1. He appears also at 14.136a (plus-line in Zenodotus; cf. page 114n17, above), 16.196 (leading one of the five Phthian contingents), 17.555, 561 (Athena disguised as Phoenix appearing to Menelaos), and 19.311 (list of basileis who stay to weep with Achilles).

[ back ] 2. Aristotle himself links arguments to or from the principles to races that proceed from the judges to the end, or the reverse: Nicomachean Ethics 1095a33–1095b2.

[ back ] 3. Kakridis 1949:65–83; Frame 2009:171n69, 216n117.

[ back ] 4. Lohmann 1970:15–18. (Only after Nestor’s speech is Phoenix stationed at the turning-post, so Lohmann does not discuss him.)

[ back ] 5. Nagy 1990a:202–222.

[ back ] 6. Nagy 1990a:215, citing Sinos 1980:53n6.

[ back ] 7. Pausanias 6.20.15–19; Nagy 1990a:215, 1990b:210.

[ back ] 8. Van den Broek 1971:51–66. Its pairing here with the white moon-sēma may recall the simile describing Menelaos’ wound at Iliad 4.141, the woman dying ivory with phoenix.

[ back ] 9. E.g. the famous Boston Hydria, Boston 63.473.

[ back ] 10. On the phoenix-bird, see Detienne 1977:29–36 and van den Broek 1971.

[ back ] 11. Richardson 1993:221 ad Iliad 23.458.

[ back ] 12. With this conjunction of sun and moon compare the forces at work near the end of the Odyssey (Austin 1975). Works and Days 478, the only other use of the verb in early epic, is sandwiched between mentions of spring and the winter solstice. Cf. Frame’s (1978:88) remark on Augeias: “The name Augeias is related to the noun augē, which in turn suggests the ‘radiance’ of the sun. It is clear that this figure was originally connected, or even identical, with the sun itself.” See also Frame 2009:49–50.

[ back ] 13. On which see Nagy 1990a:219.

[ back ] 14. The old men are, of course, currently being embodied by younger ones. On the choral associations of this passage see Martin 2007:51–54.

[ back ] 15. Notable too is the theme, shared between the Herakles chorus and the Book 23 chariot race, of youth versus age. While the Herakles chorus is lamenting their lost youth and celebrating the young Herakles, while wishing for a double youth for the virtuous, the Iliad’s race stages two contests of youth versus age on top of one another: Menelaos versus Antilokhos, in the race, and Idomeneus versus Ajax (who jeers that Idomeneus is not the youngest, and “your eyes do not see the sharpest out of your head,” 476–477), competing to catch sight of the winning team. This theme is of a piece with the theme of reanimation at the turning-point, or point of judgment.

[ back ] 16. In addition to the evidence that follows, Nagy (1990a:220) points out that σῆμα is a cognate of Skt. dhya-, which he links through Indic dhīyas to concepts of reincarnation, somewhat as Frame links νόος / IE *nes- to “return from light and life” (see below). Nagy suggests for the chariot race a connotation of reincarnation, even without bringing in the Phoenix at the center, standing by the σῆμα.

[ back ] 17. Frame 1978:21.

[ back ] 18. Frame 1978:87–95. After discussing (pp. 58–62) the “gates of day and night” in Parmenides and Hesiod and in the Telepylos episode (Odyssey 10.81–86), Frame discusses (pp. 92–93) Nestor’s home Pylos, noting that Herakles wounds Hades en Pulōi en nekuessin, Odyssey 5.397.

[ back ] 19. See, e.g., Whitman 1958:263–264; Kullmann 1960:336–355; Richardson 1993:202, 249; Frame 2009:170–172, 205–216.

[ back ] 20. Cf. Nagy 1990a:208–212.

[ back ] 21. This is stated explicitly by Philostratus (Imagines II.7), explaining that Menelaos arranged that Antilokhos, the youngest Achaean, be the one to deliver the news of Patroklos’ death in order that Achilles be distracted by touching Antilokhos and crying. Of course, in terms of the development of the tradition, Patroklos may be designed as a premonition of Antilokhos.

[ back ] 22. Odyssey 24.78–79; cf. Nestor’s speech at Odyssey 3.103–119.

[ back ] 23. Cf. Frontisi-Ducroux 1986a:50; Martin 1989:188–189.

[ back ] 24. Cf. above, Chapter 1, “Menelaos and the Empty Helmet.”

[ back ] 25. Richardson 1993:229, ad 23.555–556.

[ back ] 26. For a survey of the phoenix in classical and Christian traditions, see van den Broek 1971. According to him (pp. 393–394), there are only nine extant mentions of the bird (in Greek or Latin) before the first century CE.

[ back ] 27. Van den Broek 1971: Ch. 5; on Hesiod fr. 304 M-W, see pp. 76–112.

[ back ] 28. On Nestor’s longevity (“sole survivor from a former era”) see Frame 1978:113–114.

[ back ] 29. Van den Broek 1971:261–304.

[ back ] 30. Or his source, Hecataeus.

[ back ] 31. Figure 6 photo by Flickr user kairoinfo4u. See also in van den Broek 1971, which gives the caption (p. 425): “Mural painting in tomb of Irenifer. Del el Medineh; 19th dynasty (ca. 1345–1200 BC). ”

[ back ] 32. See van den Broek (1971:Pl. I, 2): “benu in willow tree next to grave of Osiris.” Mural painting in tomb of royal scribe. Van den Broek says “probably second century B.C.”

[ back ] 33. Tran 1964 Pl. X, 2. Bird with uraeus with solar disk and lunar crescent, perched on an open sarcophagus with Osiris mummy, first century CE. Cf. van den Broek 1971:242 and n4.

[ back ] 34. Cf. van den Broek 1971: Ch. 7, “The Phoenix as Bird of the Sun,” sect. 2, “Escort of the Sun.”

[ back ] 35. Tombs and skopoi are linked in the Iliad. At 2.791–792, Iris disguises herself as Polites, who sat as a skopos on a burial mound. At 24.799, after the Trojans heap up Hektor’s burial-mound (σῆμα), skopoi seat themselves “around”: ῥίμφα δὲ σῆμ’ ἔχεαν, περὶ δὲ σκοποὶ εἵατο πάντῃ. Here perhaps the skopoi were seated on the mound facing outward in various directions.

[ back ] 36. Cf. Herodotus on the Epaphus/Apis bull, 3.27–29. Like the phoenix, the bull appears only after a long interval, at which time the Egyptians hold festivals. Like the phoenix-horse, Apis is identified by sēmeia, among which is a white square (or as a variant reading has it, a triangle) on its forehead and an eagle on its back. The Apis bull is born from a lightning bolt striking a cow who is no longer able to conceive offspring “into her belly.” Does the Apis bull, then, arise from her ashes? Herodotus tells the story of another solar cow, the one made by Mycerinus in which he buried his daughter (2.129–134). This cow, exhumed every year to see the sun in accordance with the daughter’s wishes, is covered with a φοινικέῳ εἵματι, with her head and neck covered with gold. Between her horns is a “golden imitation of the circle of the sun.” Given Egyptian proclivities to solar headgear, all this would be unremarkable, except that Herodotus associates these creatures with, respectively, an appearance after a long interval of years, and an annual reanimation through a sighting of the sun. One is tempted to take into account Mycerinus’ rape of his daughter (and only child) here. Note his pathetic attempts at annual reanimation, followed by comical attempts at immortality through abolishing the difference between night and day.

[ back ] 37. Carpenter’s (1946) theory that Phoenix’s autobiography slots him into the Salmoxis myth came to my attention after I had drawn the connection between Phoenix and the phoenix bird. Carpenter adduces the fact that Phoenix rules over the Dolopians in Phthia, in which Halos is located, and Herodotus situates at Halos a story that Carpenter links to the Salmoxis cult (p. 122–123). He also cites the odd feasting during Phoenix’s house arrest as parallel to the “town banquet hall from which the victim is led out with pomp and sacrificial ceremony to his death.” The link to the Salmoxis story seems to me tenuous. But since the Salmoxis/hibernating bear myth complex is basically a solstice/rebirth myth, it is strange that Carpenter does not mention the phoenix bird in his discussion of Phoenix (1946:170–172).

[ back ] 38. Griffin 1977:42. For Griffin, this is further evidence of the Cycle admitting “miracles of a sort Homer does not.” But it is striking that the Nostoi or its tradition made this link; or else, that both epics draw on a traditional description of magical rejuvenation. Lucian Navigium 44–45 uses ἀποξύω in the context of a fantasy of living one thousand years by means of a magic ring, a fantasy containing a reference to the phoenix-bird and “shedding old age.” ἀποξύω is used by the person making fun of such a fantasy, to say he forgot the ring to “scrape off the vast quantities of snot” (i.e., drivel), clearly responding to the fantasizer’s ἀποδυόμενον τὸ γῆρας. The latter is what a snake does; the “stripping” is what magic does.

[ back ] 39. Gresseth (1964:93–94) connects Alkyone/halcyon and the phoenix-bird but does not make a connection to the Homeric character Phoenix.

[ back ] 40. This Book 24 scene nightmarishly reenacts the chariot race in Book 23, but it also bookends the passage in Book 23 (lines 13–14) where Achilles leads the Achaeans in driving their horses around Patroklos’ corpse three times.

[ back ] 41. On Patro-klos’ name as a sēma, see Sinos 1980:48–49; Nagy 1990a:216.

[ back ] 42. On the ramifications of this allusion to the phoenix on Delos see Ahl and Roisman 1996:53–58.

[ back ] 43. The story in Herodotus has “elements of sun mythology as preserved in an actual cult to Helios” (Frame 1978:43–44).

[ back ] 44. In some versions, the Dioskouroi steal cattle from the Apharidae. On the Dioskouroi and their relation to the Vedic twins the Nasatya (“they who bring back to life and light”), see Frame 1978:140–142; Frame 2009:21, 72. Levaniouk (1999:128–129), in the context of discussing the dense links between the halcyon and the pēnelopes, who “come from the limits of the earth,” remarks that the diction of the Iliad passage suggests Apollo carried Marpessa to the streams of Okeanos. Cf. Levaniouk 2011: Ch. 17.

[ back ] 45. See Frame 1978:38–53 on Circe (including p. 44, on Euenios), and p. 92, on Melampus.

[ back ] 46. Phoenix’s autobiography would not in itself suggest solar connections. Yet many details slot into such an interpretation. Aside from the motif of “taking over for one’s father”—in Phoenix’s case, like Oedipus, in bed and as a would-be patricide—Phoenix escapes from a house resembling Night and Day in Theogony 744–757 and other solar locations (Iliad 9.464–473):

ἦ μὲν πολλὰ ἔται καὶ ἀνεψιοὶ ἀμφὶς ἐόντες

465 αὐτοῦ λισσόμενοι κατερήτυον ἐν μεγάροισι, = Odyssey 9.31 (Circe)

πολλὰ δὲ ἴφια μῆλα καὶ εἰλίποδας ἕλικας βοῦς cf. Odyssey 9.46 (Ciconians)

ἔσφαζον, πολλοὶ δὲ σύες θαλέθοντες ἀλοιφῇ

εὑόμενοι τανύοντο διὰ φλογὸς ̔Ηφαίστοιο,

πολλὸν δ’ ἐκ κεράμων μέθυ πίνετο τοῖο γέροντος. cf. Odyssey 9.45 (Ciconians)

470 εἰνάνυχες δέ μοι ἀμφ’ αὐτῶ̣ παρὰ νύκτας ἴαυον·

οἳ μὲν ἀμειβόμενοι φυλακὰς ἔχον, οὐδέ ποτ’ ἔσβη cf. Theogony 749

πῦρ, ἕτερον μὲν ὑπ’ αἰθούση̣ εὐερκέος αὐλῆς, cf. Theogony 752–753

ἄλλο δ’ ἐνὶ προδόμω̣, πρόσθεν θαλάμοιο θυράων.

But my kinsmen and cousins surrounding me

pleaded and tried to restrain me in the halls;

many fat sheep and rolling-gaited, spiral-horned cattle

they were slaughtering, and many pigs, blooming with fat,

being singed, were stretched over the flame of Hephaistos,

and much drink out of jars was drunk—the old man’s.

For nine nights they slept alongside me, by night;

they kept watch, exchanging shifts, and never was extinguished

the fire, one under the portico of the walled courtyard,

and one in the hall, in front of the bedroom doors.

465 αὐτοῦ λισσόμενοι κατερήτυον ἐν μεγάροισι, = Odyssey 9.31 (Circe)

πολλὰ δὲ ἴφια μῆλα καὶ εἰλίποδας ἕλικας βοῦς cf. Odyssey 9.46 (Ciconians)

ἔσφαζον, πολλοὶ δὲ σύες θαλέθοντες ἀλοιφῇ

εὑόμενοι τανύοντο διὰ φλογὸς ̔Ηφαίστοιο,

πολλὸν δ’ ἐκ κεράμων μέθυ πίνετο τοῖο γέροντος. cf. Odyssey 9.45 (Ciconians)

470 εἰνάνυχες δέ μοι ἀμφ’ αὐτῶ̣ παρὰ νύκτας ἴαυον·

οἳ μὲν ἀμειβόμενοι φυλακὰς ἔχον, οὐδέ ποτ’ ἔσβη cf. Theogony 749

πῦρ, ἕτερον μὲν ὑπ’ αἰθούση̣ εὐερκέος αὐλῆς, cf. Theogony 752–753

ἄλλο δ’ ἐνὶ προδόμω̣, πρόσθεν θαλάμοιο θυράων.

But my kinsmen and cousins surrounding me

pleaded and tried to restrain me in the halls;

many fat sheep and rolling-gaited, spiral-horned cattle

they were slaughtering, and many pigs, blooming with fat,

being singed, were stretched over the flame of Hephaistos,

and much drink out of jars was drunk—the old man’s.

For nine nights they slept alongside me, by night;

they kept watch, exchanging shifts, and never was extinguished

the fire, one under the portico of the walled courtyard,

and one in the hall, in front of the bedroom doors.

[ back ] 47. Frame, in Hippota Nestor (2009), revises his earlier view (Frame 1978) that Nestor’s name had no meaning for the Homeric poets. But the later work still distinguishes earlier and later stages of Greek epic in terms of the meaning of *nes-, which as “return from death to life” did not “survive into the Homeric era” (p. 39), asmenos in the Odyssey’s lines about return from death (no longer understood as a verb), and the traditional refrain about “return to life.” But Frame notes that classical Greek asmenos still occurs “in the context of a ‘return to the light’” (Frame 2009:42n78). Since the Homeric poems may have taken shape during New Year festivals such as the Panathenaia, a context that features a turn of the sun is not so remote. Cf. Cook 1995: Ch. 5, and see below, pages 192–193 (on the calendar of the Iliad and the halcyon myth) and 304–305 (on the winter solstice in Odyssey 15).

[ back ] 48. I do not mean to suggest a close connection here between either of these works and what an audience member of the solo Iliad performer would witness. Rather these works seem to reflect on the role of Nestor and Phoenix in Iliad 23, and traditions related to it, in a way that bears upon Phoenix’s pivotal position and the parallels between his own mythology and Nestor’s. What we see in Iliad 23 in turn finds more histrionic expression in Phoenix’s Iliad 9 speech.

[ back ] 49. Phoenix is depicted as Nestor’s companion, facing him, or else positioned opposite him, at many important events: LIMC Nestor 1064, listing entries 15, 19, 25–27, 29 (which must be an error for 28), 34.

[ back ] 50. LIMC Nestor 26; for bibliography, see LIMC Achilles 487. Höckmann (1982:84), following Furt-wangler, interprets Nestor and Phoenix on this vase as occupying Achilles’ tent. She suggests this scene is not meant to be simultaneous with the sacrifice; rather, perhaps the painting draws on a version in which Nestor told Phoenix about the gruesome sacrifice in Achilles’ tent. Höck-mann however would separate the figures in the tomb from the sacrifice around the corner.

[ back ] 51. The plan of the tomb in Figure 10 is by Louis-garden, used under the CC BY-SA 3.0 license. The nineteenth-century reconstruction by Carlo Ruspi in Figure 11 is also featured in Buranelli 1987:180. A 3-D tour of the tomb is available at http://www.canino.info/inserti/monografie/etruschi/tomba_francois/tomba_francois_1.htm.

[ back ] 52. Rebuffat and Rebuffat (1978) make a case for Vel Saties being a historical ancestor of the individual who commissioned the tomb, rather than this individual himself.

[ back ] 53. Coarelli 1983:58–59.

[ back ] 54. Buranelli 1987:101.

[ back ] 55. I note that another palm is depicted in the dromos of the tomb, with a serpent. On the association between the phoenix bird and the palm (phoenix), see van den Broek (1971:52–60, 183), for whom the link is a late development, via Lactantius inspired by Ovid. Hubaux and Leroy (1939:103–104) list longevity and notional asexuality among the features common to tree and bird. (For example, note Aristotle fr. 246: palms are ἄνορχοι and therefore called eunuchs.) This last is interesting in light of Phoenix’s sterility. Hubaux and Leroy’s comparisons are dismissed by van den Broek (1971:54n2), despite his discussion later (357–389) of the sexuality of the phoenix bird. Van den Broek does not discuss the Iliadic Phoenix. Thierry Petit (personal communication, 2015) suggests that the phoenix (palm) may be the origin of the tree of life motif in Near Eastern art. For Höckmann (1982:87) the palm is a general allusion to Troy.

[ back ] 56. The Nestor–Phoenix pairing is not only, I am offering here, an ennobling “complementary analog” or “resonating gloss” for the Etruscans across from them (Brilliant 1984:34; cf. Rebuffat and Rebuffat 1978). The artist, as Brilliant puts it on the same page, “deliberately blended this diverse cultural and ethnic material to create a new narrative cycle of death and transportation.” Phoenix and Nestor act as more than mirrors within that project.

[ back ] 57. Maggiani 1983:78.

[ back ] 58. Mycenaean and Dark Age tombs did, of course, contain horse burials, some of which are thought of as chariot teams, but I am not suggesting anything corresponding to this for the François Tomb.

[ back ] 59. This may be strengthened by the palms over their heads; see above n55.

[ back ] 60. Drawing after Knox 2015: 174, with additions and modifications.

[ back ] 61. Pugliese Carratelli 1990:88, fig. 71.

[ back ] 62. Pugliese Carratelli 1990:88.

[ back ] 63. See Pugliese Carratelli 1990:89, fig. 73. These two figures are framed by a tent, although the figure following it to the right, presumably Achilles again, seems to have a shield hanging on a wall behind him.

[ back ] 64. Pugliese Carratelli 1990:86. Thierry Petit (personal communication, 2015) points out the relevance of Herakles’ apotheosis in a chariot to the symbolic complex of the chariot and reanimation. Perhaps the damaged panel depicted just this? It would certainly be in keeping with the proliferation of chariot scenes. Herakles on the pyre, followed by his apotheosis, resembles the phoenix bird; this scene roughly faces Phoenix and Achilles on the opposite wall.

[ back ] 65. Pugliese Carratelli 1990:86.

[ back ] 66. Does the damage at the other end of the chariot race leave room for Nestor?

[ back ] 67. See page 154n109 above. The gestural/proxemic analogy between Phoenix and Priam may have been even more obvious to someone who had seen the Iliad performed. By this I mean the literal gestural enactment, however this is done. For another perspective on the parallel between Phoenix and Priam in terms of enactment, see Taplin 1992:80. According to Taplin’s scheme, the bed made up for Priam in Book 24 parallels that made for Phoenix in Book 9—closing the first and third days of performance respectively.

[ back ] 68. Photo by Wikimedia Commons user Magistermercator, reproduced under the CC BY-SA 3.0 license. See Price and Van Buren 1935, Plate 12 for a reconstruction of the original garden plantings.

[ back ] 69. Jenny Strauss Clay (Clay 2011:110–115; cf. Clay 1994) recalls the story of Simonides reconstructing the positions of banqueters after they have been killed and connects it to the “dais of death” dealt out to the suitors of the Odyssey. Clay (p. 113) notes that “the poet provides us with three circuits around the great hall.” She further relates the “path of song” to the use of various forms of loci (both actual places in the story, and the artificial use of loci such as in a memory palace) by storytellers and orators.

[ back ] 70. The distinction between poetics and presence bears some relationship to that between noos and nostos as discussed by Frame (1978). Which term corresponds to which depends on one’s point of view. Poetics as plot bears a resemblance to nostos as journey. But nostos as a reemergence can be compared with presence, an emergence into the body of the performer.

[ back ] 71. See above page 138n74. Frame (2009, encapsulated at pp. 599–600) argues that secrecy characterizes the sections of the Homeric poems associated with Nestor or the Neleids.

[ back ] 72. See above Chapter 2, n78.

[ back ] 73. Fenno 2007; Whitman 1958:257.

[ back ] 74. Austin 1975; Nagy 1990a:225; Frame 1978; Levaniouk 2008:28–35. Regarding the Doloneia’s (Iliad 10’s) contested status in this scheme, perhaps it “extends” this central night to extraordinary length just as does the winter solstice operating in the Odyssey. See below, Chapter 4.

[ back ] 75. Compare Otterlo 1948 and Douglas 2007:101–124, esp. Fig. 12, showing Night 4 (the Embassy) as the mid-turn of the minor ring of eight days, which in turn forms the mid-turn of the major ring, Fig. 13, and Table 8.

[ back ] 76. Douglas 2007:109.

[ back ] 77. Whitman 1958:281; cf. the relevant section of his full fold-out chart. The discussion of ring composition here also appears in Kretler 2018.

[ back ] 78. Nagy 1990a:36–37. The nightingale (Odyssey 19) and the halcyon (Iliad 9) lament their children. They both are entangled with the thought of a woman (Penelope/Kleopatra), not only thematizing her grief but trying to represent the levels of her consciousness. The halcyon in Iliad 9 points to a similar depth within a woman that the nightingale does for Penelope. Levaniouk connects the poetics of the halcyon to that of the nightingale (Levaniouk 1999; Levaniouk 2011: Ch. 17).