-

Graeme D. Bird, Multitextuality in the Homeric Iliad: The Witness of the Ptolemaic Papyri

Introduction

1. Textual Criticism as Applied to Biblical and Classical Texts

2. Homer and Textual Criticism

3. The Ptolemaic Papyri of the Iliad; Evidence of Eccentricity or Multitextuality?

Appendix A

Appendix B

Bibliography

Chapter 1: Textual Criticism as Applied to Classical and Biblical Texts

The primary goal of textual criticism has traditionally been to establish the actual text that the author wrote, so far as this is possible. [1] This needs to be done because, in the case of Classical and biblical authors (and sometimes in the case of more recent texts), the autograph, or author’s original manuscript, no longer exists. In its place there are surviving manuscripts, each of which is a copy of an earlier manuscript, often at an unknown number of steps removed from the autograph.

The situation just described includes three assumptions: first, that there actually was an author; second, that the author left behind an original manuscript; and third, that this original is worth trying to reconstruct. The further complication frequently arises in which it appears that the author has left more than one manuscript of a particular work, leaving the question as to which of these versions should be treated as the authoritative one (with the default generally, but not always, being the last one). I mention this because recently there has been vigorous debate over the second and third of these three assumptions, especially in relation to texts dating from the time of Shakespeare on, but also in connection with biblical and classical texts. However, for the sake of the present discussion I will proceed with these three assumptions in mind.

The texts of classical and biblical authors have come down to us in widely varying states of abundance: at one extreme, for example, the two chief works of the Roman historian Tacitus (Annales and Historiae) each survive in a single medieval manuscript [2] ; at the other, Homer’s Iliad is currently represented by more than 1,900 manuscripts (at least 1,500 of which are on papyrus, although many of these of a fragmentary nature). [3] And for the Greek New Testament, there survive more than 3,000 Greek manuscripts (interestingly, with papyrus comprising a tiny minority—94, or around 3 percent). This last figure does not include more than 2,000 “lectionaries” (containing portions of the Gospels and Epistles arranged for daily and weekly lessons), “versions” (translations into languages such as Latin, Syriac, Coptic, Gothic, Georgian, and Armenian), or quotations in early church fathers; each of these different sources of evidence plays a significant role in efforts to establish the original text of the Greek New Testament. [4]

How one approaches the process of creating an edition of a Classical author will obviously be affected by the quantity of extant evidence. The overall procedure will also be determined by the textual editor’s modus operandi (on which more below), but generally follows the same set of steps, traditionally given by their Latin names [5] :

i) recensio: sorting through and collating the surviving manuscript evidence.

ii) examinatio: an attempt to establish the earliest possible version of the text.

iii) emendatio: correcting the text when none of the surviving manuscripts appears to preserve the correct reading; this may include making a conjecture (see below). Also referred to by the term divinatio, a term which imparts perhaps a little too much mystique to the process. [6]

The seemingly straightforward elements of textual criticism are: whenever the surviving manuscripts agree on a piece of text, this most likely represents the original; whenever they disagree over a particular passage, be it something as apparently trivial as the alternate spelling of a word or the use of a different word, or something as significant as the omission of a whole section in one manuscript and its inclusion in another, one must decide which of the two or perhaps more options is the best—in other words, which version represents the original words of the author?

The difficulties arise when one actually looks closely at this process of deciding. What may at first glance seem like a simple matter of preferring one reading over another—and occasionally it may be that simple—in reality is determined both by the nature of the evidence and by the proclivity—some might even say the eccentricity—of the textual editor. Indeed, as we shall see, sometimes in spite of the fact that all extant witnesses present the same text, nevertheless it is clear (at least to some) that the text is “corrupt” and needs to be “emended.”

A major part of the initial process of recensio is the grouping into families of the extant manuscripts, an analysis also known as stemmatics, in order to discover how errors that arose early in the textual tradition have been passed down with repeated copying. In other words, manuscripts which contain such “shared errors” are most likely members of a “family,” and have passed on their errors from one “generation” of copying to the next, much as members of a human family pass on their various genes to their offspring. By so doing one is able to decide which manuscripts are “dependent” upon others, and hence are of less importance in determining the correct text. Such dependent manuscripts are known as codices descripti, and the process whereby they are “removed” from further consideration is called eliminatio codicum descriptorum. [7] The New Testament scholar J. A. Bengel (1687–1752) was among the first to stress that manuscripts must be weighed, not merely counted [8] ; in other words, if one or more manuscripts can be shown to depend on (i.e. derive from) an older manuscript—which is extant—then these dependent later manuscripts contribute little or nothing in terms of weight to any debate over variant readings. [9] Thus the evidence for and against a particular reading will always take into account this factor of dependence, rather than any simple counting of numbers of manuscripts. [10]

I note at this point that the history of textual criticism, particularly over the last three centuries, has involved a significant mutual influence between the fields of classical and biblical literature. I refer in particular to such scholars as Richard Bentley, who achieved breakthroughs in both Homeric and New Testament (NT) studies [11] ; J. G. Eichhorn, the Old Testament scholar who had an important influence upon F. A. Wolf and his Prolegomena [12] ; and Karl Lachmann, who refined to an unprecedented degree the method of the study of manuscripts, as exemplified in his editions of Lucretius and the Greek New Testament. [13] In addition, the quantity of surviving material available for studying the text of Homer is far greater than for any other classical author, and is only exceeded in ancient Greek literature by the abundance of textual evidence pertaining to the New Testament. [14] It is reasonable to expect that techniques which have been developed to deal with such a wealth of variant readings in this latter text will in all likelihood be of assistance in handling the smaller—but equally, if not more divergent—quantity of variants that survive in our witnesses to the text of Homer. I shall therefore refer at times to text-critical methods employed by scholars working in this closely related field.

Bengel is also considered the first to formulate the canon of textual criticism which regards the more difficult reading as preferable to the less difficult—the primacy of the lectio difficilior, or in his words proclivi scriptioni praestat ardua [15] (also lectio difficilior potior/melior). The scribe, in his role as copyist, is most unlikely to change a word or passage which reads satisfactorily into something which presents problems of clarity, smoothness, or unusual grammar. He is much more likely to “smooth out” passages which already present such “difficulties”: this smoothing out process may be conscious or even unconscious. Thus if we are confronted with two variant readings in a particular passage, one “easier” and the other “harder,” we need to be able to explain how the two arose. A common scenario is that the harder reading is original (i.e. lectio difficilior potior), with the easier one having been corrupted from it by the scribe’s attempts to facilitate a difficult construction, or perhaps in order to harmonize the passage with another which conflicts with it in some way. In NT textual criticism harmonization is especially relevant in two cases. Firstly, when an account in one Gospel does not agree exactly with that in another, there is often a variant reading that aligns one account with the other. Secondly, when a NT writer quotes from the Hebrew Bible (usually via the Septuagint or LXX, the third-century BCE Greek translation used by Hellenistic Jews, and apparently also by most NT writers), and the quotation does not exactly match the original, there is frequently a variant that brings the quotation into line with the original.

An example of the harmonization of differing Gospel accounts involves the Lord’s Prayer, which occurs in two Gospels, Matthew and Luke. The version more familiar to most readers is the former, which starts:

πάτερ ἡμῶν, ὁ ἐν τοῖς οὐρανοῖς, ἁγιασθήτω τὸ ὄνομά σου …

Matthew 6:9

Our Father, the one in the heavens, let your name be hallowed …

When we come to Luke’s account, the “best” (needless to say, this term begs the question) and oldest manuscripts give a shorter version:

πάτερ, ἁγιασθήτω τὸ ὄνομά σου …

Luke 11:2

Father, let your name be hallowed …

It is generally believed (for reasons not gone into here) that the Matthean version is older, and hence “original.” Not surprisingly, several manuscripts, some early, give the longer reading for Luke, illustrating one or more ancient scribes’ efforts to bring Luke’s account into harmony with Matthew’s. In fact the urge to harmonize in this case would have been fairly compelling; of the majority of manuscripts which did not thus succumb, the NT textual scholar Bruce Metzger comments, “it is remarkable that such a variety of early witnesses managed to resist what must have been an extremely strong temptation to assimilate the Lukan text to the much more familiar Matthean form.” [16] Presumably reverence for the text will have played an important role in this.For an instance of assimilation to the Septuagint, I refer to the anonymous letter to the Hebrews, chapter 1, verses 11–12. These verses are part of a quotation from Psalm 102, verse 26. The Septuagint (in which the passage is numbered Psalm 101, verse 27, following the Hebrew Bible, in which the title of the psalm frequently counts as the first verse) reads as follows:

καὶ πάντες ὡς ἱμάτιον παλαιωθήσονται,

καὶ ὡσεὶ περιβόλαιον ἀλλάξεις (v.l. ἑλίξεις) αὐτούς,

καὶ ἀλλαγήσονται.

And they will all wear out like a cloak,

And like a garment you will exchange them (v.l. roll them up),

And they will be exchanged.

In the “best” and oldest manuscripts of the NT Hebrews passage, the words ὡς ἱμάτιον are inserted a second time into the quotation as follows:

καὶ ὡσεὶ περιβόλαιον ἀλλάξεις (v.l. ἑλίξεις) αὐτούς,

καὶ ἀλλαγήσονται.

And they will all wear out like a cloak,

And like a garment you will exchange them (v.l. roll them up),

And they will be exchanged.

καὶ πάντες ὡς ἱμάτιον παλαιωθήσονται,

καὶ ὡσεὶ περιβόλαιον ἑλίξεις (v.l. ἀλλάξεις) αὐτούς,

ὡς ἱμάτιον καὶ ἀλλαγήσονται.

And they will all wear out like a cloak,

And like a garment you will roll (v.l. exchange) them up,

And like a cloak they will be exchanged.

However, most manuscripts omit these words in an apparent attempt to harmonize the NT text to that of the LXX. Metzger remarks that the author of Hebrews inserted the words “to show that the metaphor of the garment is continued. The absence of the words from most witnesses is the result of conformation to the text of the Septuagint.” [17] (I note also that most NT manuscripts read ἑλίξεις rather than ἀλλάξεις; in two exceptional cases, one the famed א, or “Codex Sinaiticus,” the original ἀλλάξεις has been altered by a later scribe to ἑλίξεις.)καὶ ὡσεὶ περιβόλαιον ἑλίξεις (v.l. ἀλλάξεις) αὐτούς,

ὡς ἱμάτιον καὶ ἀλλαγήσονται.

And they will all wear out like a cloak,

And like a garment you will roll (v.l. exchange) them up,

And like a cloak they will be exchanged.

Of course, not all textual corruption results from a scribe’s conscious (or unconscious) efforts to make his text easier to read. Many examples of variant readings have their origin in simple mis-copying—for whatever reason (simple carelessness, tiredness, bad light, etc.) a scribe drops one or more letters, skips a word or line, writes one letter for another, etc. A. E. Housman [18] gives a useful list of errors involving transposition of letters, under various subheadings (for each example the former reading is that considered correct, the latter a corruption of it):

Trajection of one letter :

cadere in terram ~ caderem in terra

(Lucretius De Rerum Natura II 209)

Inversion of two letters :

amnis ~ manis

(Virgil Georgics I 115)

Inversion of three letters :

vomere ~ movere

(Virgil Georgics II 203)

Metathesis of syllables :

mini-me ~ me-mini

(Plautus Miles Gloriosus 356)

Transposition of two letters across an intervening spac e:

versarent ~ servarent

(Propertius IV 1 129)

Rearrangement of four or more letters :

et nigras ~ integras

(Propertius III 5 24)

I have given only one example under each heading; Housman includes twenty or thirty or more, as well as copious examples of what he calls “further change,” for example:

visceribus aerari ~ vi caesaris rebus

(Cicero De domo sua 23)

This kind of corruption often results in the substitution of a simpler word for a less familiar one, but it also may lead to a text which is actually harder to read, or even completely unintelligible. In such instances, the principle of lectio difficilior is not necessarily going to apply. [19] Sometimes a subsequent scribe may attempt to correct the error, either successfully or otherwise. Housman [20] gives further examples from verse, where meter has been a factor in the attempts of scribes to “repair” a faulty line. Below is a case where haplography (see the Appendix) has caused a word or phrase to drop out, and the demands of meter have led to another word or phrase being inserted into the lacuna. First the original text:

seu stupor huic studio sive est insania nomen

omnis ab hac cura cura levata mea est

omnis ab hac cura cura levata mea est

Ovid Tristia I.11.11–12

But whether “trance” or “madness” be the name for this pursuit,

’twas by such pains that all my pain was lightened. [21]

Evidently the second occurrence of the word “cura” was dropped, and the gap later filled with a metrical (and semantic) equivalent, so that virtually all manuscripts present the reading:

’twas by such pains that all my pain was lightened. [21]

seu stupor huic studio sive est insania nomen

omnis ab hac cura mens relevata mea est

... all my mind was relieved from this pain

According to Housman, someone thoroughly familiar with Ovid’s style would have sensed that “something has gone wrong” just by noticing, as he puts it, the “aimless change from ‘huic studio’ to ‘hac cura.’” However it took the discovery of the correct text in an inscription to compel editors to print a reading that had not survived in any manuscript. Housman expends much energy in chastising those who are too timid to depart from the manuscript tradition when circumstances call for such action: “to do so would involve recognizing that all the mss., not only some of them, are deeply interpolated; and to recognize this would cause them discomfort.” [22] A modern editor of Ovid is more willing to accept the discomfort: “a striking error at [Ovid Tristia] I. 11. 12 shows that the whole tradition may on occasion be interpolated.” [23] omnis ab hac cura mens relevata mea est

... all my mind was relieved from this pain

Finally, I give from Housman an example of a line which is presented by the manuscripts, but which is “unscannable”:

an caelum nobis ultro natura corruptum

deferat aut aliquid quo non consueuimus uti.

deferat aut aliquid quo non consueuimus uti.

Lucretius De Rerum Natura VI 1135–1136

Whether nature of herself brings to us an infected sky

or something we are not accustomed to experience ... [24]

The original reading according to Housman (essentially similar translation):

or something we are not accustomed to experience ... [24]

an caelum nobis corruptum deferat ultro

natura aut aliquid quo non consueuimus uti.

After explaining how these two lines arose by means of various corruptions, Housman concludes by saying, “ ‘natura corruptum’ could be scanned, in the ages of faith, by many a humble Christian; for true religion enabled men not only to defy tortures but to shorten the first syllables ...” of words such as corruptum. [25] natura aut aliquid quo non consueuimus uti.

In some cases respect or even reverence for the text may cause the corrupted passage, unintelligible though it is, to be faithfully transmitted down to the present. [26] An example comes from Plutarch’s Moralia 388c, where the original ὁμιλία (which is actually a modern conjecture, but evidently the original reading) has been corrupted into ὃ μὴ διὰ; though meaningless, the latter reading was nevertheless copied into subsequent manuscripts and in fact helped in the restoration of the original. [27] The process of corruption in this case is easy to see when capitals are used: ΟΜΙΛΙΑ → Ο ΜΗ ΔΙΑ. The confusion of Η for Ι involves itacism—an aural confusion, [28] illustrating the fact that ancient and medieval readers, even if alone, would read aloud; alternatively the error could have arisen through the dictation process. The variation between Δ and Λ (and often Α) is a very frequent confusion, in this case based on visual similarity (but only for capitals). In addition, since documents were written without word division, instances of mis-segmentation such as this were frequent. [29]

In addition, one must beware of concluding that just because a particular manuscript happens to be full of scribal errors, its underlying text is therefore also of inferior quality. Witness the case of a New Testament papyrus, P46, where the scribe has very carelessly copied an exemplar of high quality: “we must here be careful to distinguish between the very poor work of the scribe who penned it and the basic text which he so poorly rendered ... once they [the scribe’s own errors] have been discarded, there remains a text of outstanding (though not absolute) purity.” [30]

This brings us to the question of the quality of manuscripts, that is, the quality of the text to which they bear witness; and this in turn leads us to the spectrum of text-critical methodologies. Textual evidence is generally divided into two categories: external, i.e. the details of a manuscript’s date, provenance, stemmatic relationships with other manuscripts, etc.; and internal, i.e. the nature of the variant reading itself—its grammaticality, stylistic features, etc. The textual critic is always having to weigh these two types of evidence, and, as often as not, either consciously or otherwise, will usually tend to emphasize one more than the other when making decisions about variants. Internal evidence can be further subdivided into a) transcriptional and b) intrinsic types. [31] The former tends to deal with accidental changes to the text, and involves deciding between variants based on a consideration of how a scribe might have unconsciously altered a reading, due to such things as homoeoteleuton (words, phrases, or lines with the same ending; cf. homoeomeson and homoeoarchon), [32] mistaking of one letter for another, and so forth. Intrinsic evidence is what causes the editor to ask which of the available readings is most likely to be what the author wrote, based on considerations of style, vocabulary, thought patterns, and the like.

When we consider the various ways of approaching textual criticism, we find that there exists a wide range of methodologies. At one end of the spectrum, an editor might decide to follow one manuscript (or family of manuscripts) exclusively, departing from it only in cases of obvious corruption, and otherwise virtually ignoring all other evidence; this is the methodology of the codex optimus. To a large degree the earliest editors of classical (and biblical) texts tended to follow one or at most a small number of manuscripts, while ignoring the bulk of the evidence, which often contained better readings. Part of their justification was the fact that access to widely scattered documents was not yet convenient enough to allow full exploitation of all relevant textual evidence; as such access opened up, with improvements in modes of travel, as well as the use of photography, scholars began to use the full range of available documentation. In addition, these earlier textual editors were frequently constrained by the existence of an “entrenched vulgate”—a widely accepted text which they felt compelled to print (especially in the case of the New Testament), while relegating variant readings to the critical apparatus. [33] Although this approach is now far less frequent than in the past, Joseph Bédier (in the field of Old French literature) earlier last century advocated a return to this use of a “best text” which is only corrected in the case of obvious scribal errors, attacking the fundamentally different methodology of stemmatics. [34] One of the reasons for his hostility toward stemmatics was that a disproportionate number of stemmata, as constructed by editors, contain only two branches, a situation which allows the editor undue discretion. For if both branches present different readings, the editor must make the final choice, whereas if there are three or more branches, and two are in agreement against the third, then one is supposed to choose the “majority reading.” [35]

Criticism of the codex optimus methodology has been severe: Wolf himself condemns scholars and editors who depend excessively and slavishly upon one exemplar, as well as those who use variant readings only when an obvious textual problem appears. [36] Housman, never one to hold back when an opportunity for colorful polemics presented itself, suggested that it would need “divine intervention” to bring it about that “the readings of a MS are right whenever they are possible and impossible whenever they are wrong”; and further that such divine intervention “might have been better employed elsewhere.” [37] Tanselle characterizes the “best text” approach as illogical, “a critical approach that embodies a distrust of critical judgment.” [38] Reynolds and Wilson point out that the “best manuscript” of an author, if such really exists, can be determined only by methodically going through all the “significant” evidence—i.e. the variants of all seemingly important manuscripts—and by comparing those passages where the evidence diverges, assessing which manuscript gives the “correct” reading more often than any other. [39] My putting such terms as “significant” and “correct” inside quotation marks should alert the reader to the fact that the whole procedure involves critical judgment and experience, and is not to be reduced to some simple formula as the doctrine of the codex optimus seems to do: in fact, this latter approach almost boils down to an escape from the complexities of thoroughly examining the evidence and making what are sometimes very difficult decisions. [40]

The other extreme involves the methodology whereby external evidence is virtually ignored, and variants are weighed purely on the basis of their intrinsic (rather than transcriptional, as it appears in practice) internal probability, regardless of the number or quality of the manuscripts supporting such a variant. In NT studies this methodology is sometimes labeled as “rigorous eclecticism”; the chief criticism of this method is that a significant degree of objectivity is lost, and decisions on variants tend to be based on the editor’s preference for internal criteria. [41] Approaching textual variants in this way could conceivably lead to the scenario of a reading which is represented solely in one late manuscript being chosen, based on stylistic and other criteria, in preference to one which appears in all other texts, both early and late.

In between these two extremes lies a middle path—what has been called “rational eclecticism” (or “reasoned eclecticism” [42] )—where both internal and external evidence play a part: [43] variants are examined and decisions made based on the principle of the lectio difficilior; also by following the rule that it should be possible to show how the correct reading has been corrupted into the incorrect; and by counting and weighing manuscript support for each reading—which process naturally includes evaluating each manuscript in terms of its overall textual quality. In practice editors often tend to tilt more to the external or the internal evidence: the celebrated NT textual critic F. J. A. Hort reflects the former tendency when he says “knowledge of documents should precede final judgment upon readings.” [44] For the latter emphasis, compare Richard Bentley’s famous dictum nobis et ratio et res ipsa centum codicibus potiores sunt, ‘reason and the facts are worth more to us than a hundred manuscripts’; for him the evidence of the manuscripts had to take second place to factors of sense and style, [45] which is not say that he ignored such evidence; rather for him it could never be the final arbiter in any decision over readings. [46] Compare the more recent statement that in situations where it is not a case of demonstrable error, “most editors do indeed evaluate variants on internal grounds before accepting the results yielded by stemmatic analysis.” [47]

In the case of most classical authors, there is not enough evidence to worry excessively about pitting external and internal factors against each other—in fact often it may be obvious that the correct reading has not survived at all, and a conjecture is called for. In many cases, though, one is able to create a stemma which displays the dependence of later manuscripts on earlier ones in the form of a family tree. In some cases all surviving manuscripts can thus be successfully traced back to an “archetype,” i.e. the document from which all subsequent copies derive. In the optimal situation, this would in fact be what the author himself wrote, in other words, the “autograph”; in less ideal (but more frequent) cases one can get back to an archetype, without being certain as to whether it is also the original author’s version. In practice one can never be sure whether one’s reconstructed archetype is in fact the same as or even close to the original autograph; indeed often an archetype can be determined, but one which is patently corrupt and in need of emendation. [48] In the process of creating a stemma, one has to take into account such factors as the age of manuscripts (determined by paleographical analysis as well as internal datable references), the geographical location or provenance (and manuscripts, especially papyri, were often copied in one place and transported to another [49] ), and the elusive “quality” of the text: bad copies can be made from good exemplars [50] ; and while old manuscripts (especially papyri) may often appear to be the most faithful transmitters of the original text because of their age, [51] one should not thereby rule out readings from later manuscripts—pithily epitomized by G. Pasquali in the words recentiores, non deteriores, ‘later, not inferior.’ [52]

While it might appear that an archetype not too far removed in time from the original autograph gives grounds for thinking one has a text very close to the autograph, at least one scholar warns that textual corruptions tend to be the most frequent and even the most severe in the period immediately following the writing of the autograph. [53] And what is worse, of course, is that, although the archetype was often near chronologically to the autograph, that was “precisely the period of time when, by definition, no cross-checking from other MSS. was done and when the text’s transmission was not yet submitted to academic, editorial, or ecclesiastical surveillance.” [54] Thus if the archetype itself is corrupt, the only way to correct it is by the process of conjectural emendation. [55] Another scholar writes of the way in which classicists (as well as biblical scholars) can develop almost a reverence for the author’s original text, in spite of the fact that we can never know with certainty that we have such a text [56] ; correspondingly, one can tend to denigrate manuscripts, seeing them merely as imperfect vehicles transmitting an idealized original. [57]

In the least desirable (but still frequent, perhaps the most frequent) situation, the phenomenon of contamination (Latin contaminatio), or “horizontal influence,” will have taken place, causing errors to cross stemmatic lines in a way which obscures or even obliterates family relationships. Contamination occurs whenever a scribe does not merely copy his manuscript from an exemplar—this by itself would result in a straightforward “vertical” relationship between the two documents, with most if not all of the exemplar’s errors being transmitted to the copy, allowing the copy to be recognized as being “dependent” upon the exemplar—but in addition he “checks” or “collates” his work against a third manuscript, one which often comes from a different part of the “family tree,” or stemma. This third manuscript typically has its own distinctive characteristics, i.e. errors, and perhaps good or “original” readings which in other documents have been corrupted; it is thus “independent” of the scribe’s exemplar. In this way there arises a horizontal relationship between the second and third manuscripts—i.e. contamination. The foregoing assumes, of course, that the scribe actually does change his text to make it conform with the third manuscript; in some cases scribes do make such corrections, in other cases they leave their new copy as it is; they may even do a combination of the two, i.e. leave their new copy as it is and indicate in the margin that another reading exists, a practice which gives rise to marginal and other notes known as scholia. [58]

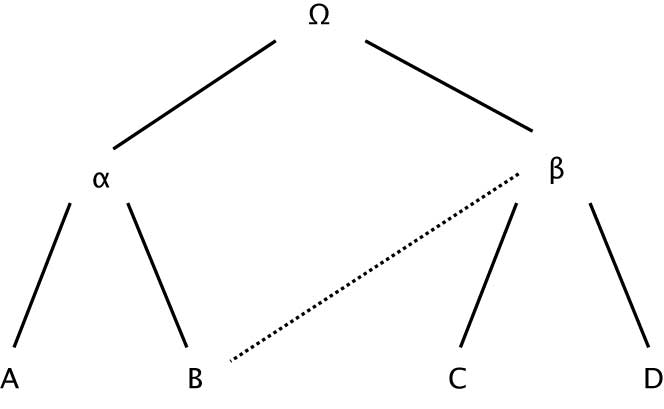

As an illustration of a simple case of contamination, consider the diagram below (Figure 1), which represents a hypothetical relationship between extant and lost manuscripts: it is a simple example of a stemma codicum, or family tree of manuscripts. The uppercase Greek letter Omega (Ω) stands for the presumed archetype, or ancestor of all manuscripts in this particular family; the lowercase Greek letters stand for non-extant manuscripts that are assumed once to have existed (and to have been exemplars for the next “generation,” i.e. “hyparchetypes”); and Roman letters stand for manuscripts that are extant.

The fact of contamination might not at first seem to be a problem; after all if scribes check their work against other manuscripts surely their final product will be of a higher quality. However, when one is weighing one variant reading against another, such a weighing must take into account the weights of the individual manuscripts (as discussed above); independent manuscripts or branches of the stemma carry more weight than those which show some dependence on each other. Thus if a particular reading is shared by two independent branches of the stemma, such as B and C in the diagram above (and thus presumably going back to both α and β, and even to the archetype Ω), it carries more weight than if it appeared in B alone (i.e. α alone, and therefore quite possibly an error that was not in the archetype Ω). But after contamination has occurred, B’s weight (regarding the reading in question) now derives, at least in part, and perhaps solely, from β, the exemplar of C, and thus the reading loses a lot of its significance and may even fall out of consideration altogether. [59]

In cases of extreme contamination, precise textual affinity can become so uncertain that the creation of a stemma becomes difficult or even impossible. This is in fact the case with several classical works, such as Virgil’s Aeneid, [60] as well as the text in general of the Greek New Testament. [61] As we shall see, similar difficulties have plagued those who would create a stemma for the manuscripts of Homer; however I shall argue that in Homer’s case both the explanation and the solution are rather different from those applicable to most ancient works. [62]

The previous discussion has been dealing only with external evidence—internal evidence would also play a part in such a weighing of evidence, but the point is that contamination frequently weakens the force of external evidence, by lessening or even eliminating the importance of a manuscript previously thought to be of value. The problems caused by contamination, and the limitations it imposes on the stemmatic method, [63] have not always been fully recognized; Paul Maas’ book on textual criticism virtually ignored it, [64] but later works by e.g. G. Pasquali [65] and M. L. West [66] have given it more appropriate treatment. Reynolds and Wilson caution us against extremes—particularly that of assuming that contamination is so rampant in textual traditions that the stemmatic method is of no use. [67] In the field of New Testament studies, the factor of contamination (or “conflation”) was one of the three main reasons why Westcott and Hort removed from serious consideration the TR (“Textus Receptus”) as a significant textual family (or, much less likely, as the original NT text). The TR, or “Syrian text-type,” as they called it, was found to be full of “conflate” readings deriving from the two earlier text-types—the “Alexandrian” (which they, somewhat presumptuously, finally called “Neutral”) and the “Western.” As the Syrian readings were compared with those from the other two text-types, “their claim to be regarded as the original readings is found gradually to diminish, and at last to disappear.” [68]

We have considered some of the issues which arise during the process of recensio and emendatio. At this point it would be well to step back and think more about the actual benefits of textual criticism, and to look at some examples. I refer to Martin West’s book on textual criticism, where he discusses these benefits. [69] As I do so, I will be occasionally mentioning the situation regarding the text of Homer, with a view to discussing it in greater detail in the next chapter.

Firstly, and most obviously, textual criticism aims to allow us to determine (with a more or less reasonable degree of certainty) what precisely the author wrote. [70] Although this might seem natural and obvious enough, such precision can in fact have important consequences if the author was writing, for example, history or philosophy: there could be cases where the historicity, or at least important details, concerning a person, place, or battle hangs upon the veracity of a particular variant reading, or where a crucial thread of philosophical thought depends on ascertaining the precise wording of an argument. Details regarding economic situations or military events could even be obscured by confusion between letters, since letters of the alphabet were employed to represent numerals (in both Greek and Latin).

An example of this latter type of confusion occurs in Thucydides III 50.1. The manuscripts read χιλίων (1000), whereas a more “reasonable” number in the context would be τριάκοντα (30). Obviously it would be hard to see how corruption could have occurred if the words themselves were originally written; however if we allow that “one thousand” was represented by the capital letter, Α and “thirty” by Λ’, the confusion is rather easier to understand. [71]

An historical example occurs in Herodotus VI 105–106, and concerns the name of the Athenian who ran to ask for help from the Spartans against the Persians (who had just landed at Marathon). Was his name Φιλιππίδης or Φειδιππίδης? Most modern editors print the former; although the manuscript evidence is less good than that for Φειδιππίδης, there is good support from other authors (Pausanius, Plutarch), and the name Φιλιππίδης is a common Athenian name. Φειδιππίδης, however, appears to be the humorous creation of Aristophanes (see Clouds 67), but it does have better manuscript authority; in addition it must be considered the lectio difficilior in this case (because of its comparative rarity, and, some have claimed, the inappropriateness of Aristophanes using in jest a name “consecrated in the tale of Marathon”; (but was he in fact constrained by any such scruples?), and therefore perhaps more likely to be the original reading. Without being certain as to which reading is genuine, one can easily see how one might have arisen from the other: when written in capitals, the letters Δ and Λ have become confused, along with the fact that the first syllables of each name (ει and ι) eventually came to be pronounced in the same way (itacism). [72] Of course such confusions, the first visual and the second audible, will also tell us something about the date at which (approximately) the error is most likely to have occurred: capital letters can obviously only be confused in an uncial manuscript (including papyri), while the convergence of the above vowel sounds occurred between the late classical and Byzantine periods. Thus we can say that this particular error most likely originated sometime between about the third and eighth centuries CE, before uncial manuscripts were superseded by minuscules.

The above example illustrates the weighing of the internal and external evidence, some consideration of the lectio difficilior, and an attempt to explain how one reading might have resulted from the other through confusion of script and phonology; despite these considerations, in this particular case one reading does not present itself as unmistakably “correct.”

Needless to say, these types of copying errors (confusion of written letters, confusion of similar sounds) occur frequently in the transmission of the texts of all classical authors, and must not be ruled out in any examination of the text of Homer. However my claim will be that only some of the surviving variant readings in our text of Homer can be explained by invoking this sort of scribal error, and that in fact a significant number cannot be explained in this way; rather, the variants in question contain divergences so substantial and so early [73] that they lead one to conclude that there was no archetype in the usual sense.

To consider another example, we find in Plato’s Timaeus an instance of significant variants in a philosophical passage. In 69–70 the soul, chest, and heart are being described; in 70A–B the following four variant readings occur, along with a scholarly conjecture: [74]

a) τὴν δὲ δὴ καρδίαν ἅμμα τῶν φλεβῶν ... κατέστησαν.

(‘the heart, the knot of the blood vessels ... they established’) This is generally accepted as the correct reading; however the word ἅμμα is fairly rare and hence likely would have seemed unfamiliar to a scribe. This could explain a conscious change of the text.

b) τὴν δὲ δὴ καρδίαν ἅμα τῶν φλεβῶν ... κατέστησαν.

Assuming that the first reading is correct, this variant could have arisen consciously, as a scribe’s replacement of the unfamiliar ἅμμα with the much more familiar ἅμα (‘at the same time’). Or, treating it as an unconscious error, it could be explained as a case of haplography (accidentally writing one letter for two)—helped by the fact that the resultant word was indeed familiar. Alternatively, the reading could be due to the fact that in early uncial writing geminate consonants were as a rule written once only. However, when all is said and done, this reading gives an untranslatable clause. Renehan points out that Galen quotes this passage with this reading three times, indicating that the textual corruption is very early. [75]

c) τὴν δὲ δὴ καρδίαν ἀρχὴν ἅμα τῶν φλεβῶν ... κατέστησαν.

This reading, characterized as a Renaissance conjecture (it is found only in some later mss.), was occasioned presumably by the fact that Aristotle often calls the heart the ἀρχὴν τῶν φλεβῶν (‘source of the blood vessels’); but of course the rationale behind the conjecture is to “correct” the unsyntactical ἅμα by supplying the missing antecedent for the genitive φλεβῶν.

d) ἄναμμα δὲ [sc. ὁ Πλάτων φησὶ] τῶν φλεβῶν τὴν καρδίαν ...

(ἄναμμα usually means ‘ignited mass’; perhaps here ‘attached knot’) This is “Longinus” ’ paraphrase of the passage; note that he preserves evidence of the original reading. However when one weighs the manuscript evidence, this variant can be explained as an example of dittography—the accidental writing twice of something (in this case the two letters αν at the end of καρδίαν) which originally occurred only once: ΚΑΡΔΙΑΝΑΜΜΑ → ΚΑΡΔΙΑΝΑΝΑΜΜΑ. Note that in the “Longinus” paraphrase the conditions for dittography are no longer apparent, since καρδίαν now no longer precedes ἄναμμα; this means that the corruption must have antedated him.

e) τὴν δὲ δὴ καρδίαν ἀρχὴν νᾶμα τῶν φλεβῶν ... κατέστησαν.

This is a modern conjecture: indeed the conjectured word νᾶμα (‘stream’) occurs elsewhere in the Timaeus (and is frequent in Plato generally). However its meaning seems inappropriate in this passage. [76]

This example illustrates several of the “canons” discussed above: the preferring of the lectio difficilior, the fact that one can show how the true reading was corrupted into one or more of the others (utrum in alterum abiturum erat? [77] ), and the non-acceptance of a conjecture if it does not actually improve the text. This much relates to internal evidence, and in this case both transcriptional and intrinsic types come into play. [78] Additionally, the weight assigned to external evidence plays a role, with the oldest manuscripts preserving the genuine reading; choosing this correct reading is a rather straightforward matter in this case.

If the first benefit of doing textual criticism is to determine the actual words of the author, then a second is that by closely examining and weighing variant readings, one is led into a deeper knowledge of the author’s style and manner of thinking than might otherwise have been the case. [79] Merely to ask such seemingly abstruse questions can lead to a close examination of an author’s style, and linguistic and (for poetry) metrical usage. Our knowledge of his personal sensitivities may depend heavily upon the care with which we weigh and decide between different readings. This can enrich our knowledge of the language itself, as well as of the relationships between authors of the same and related genres. Conversely, of course, one’s familiarity with an author’s style and content will enable him/her to make more informed decisions about what is the correct reading in cases where variants occur, and even to detect cases of “corruption” where no variant readings have survived. [80]

I have discussed how the editor of an ancient work must weigh both the internal and the external evidence when deciding which variant to print in the text, and which to relegate to the apparatus. Not infrequently there will be cases when none of the extant manuscripts gives a reading that can be considered original. Either there is one sole surviving reading which is patently incorrect, or two or more variants which are all faulty; or there may be a gap in the text (lacuna) which must be filled in order for the passage to make clear and coherent sense. There are also “borderline” cases, where the text before us may be correct as it is, but one or more scholars feel uncomfortable enough with it to propose their own replacement.

In each of the above cases, a “conjecture” may be proposed, the goal of which is to “repair” the text at the point at which it is evidently faulty; a conjecture which gains general acceptance then becomes known as an “emendation.” The OED defines “conjecture” as “the proposal of a reading not actually found in the traditional text”; and “emendation” as “the correction (usually by conjecture or inference) of the text of an author where it is presumed to have been corrupted in transmission,” and also “a textual alteration for this purpose.” [81] In practice, however, the two terms are often interchanged, as well as sometimes being used in conjunction, viz. “conjectural emendation.” One specialist puts it as follows: “If a conjecture is defined as a scholarly guess which attempts to improve the text at hand, then, strictly speaking, an emendation is a successful conjecture, one that actually removes a fault.” [82] The art of conjecture was known as divinatio by the Romans, although as Tarrant notes, this term originally did not have mystic force but rather meant little more than guesswork. [83]

There is a range of views on how frequently conjecture should be applied, both in general and in specific cases; those writers who describe scholars at each end of the spectrum tend to excel in the use of both colorful and polemical language. For instance, those exhibiting one tendency have been described as “suffering from the occupational disease of the emendator—the final inability to leave well alone”; [84] elsewhere this affliction is described as pruritas emendandi—the ‘itch to emend’ [85] ; and Bentley, for whom emending texts was as natural as breathing, has been described as “wad[ing] knee-deep in the carnage of his emendations.” [86]

The opposite extreme is found in the case of most NT textual critics. Bentley himself is quoted as admitting that “in the sacred text ... there is no place for conjecture or emendation,” although later he says he will add any such proposals separately in his Prologomena. [87] Other scholars seem to have come to the consensus that there is such an abundance of textual evidence that the original reading must survive somewhere, and it is the textual critic’s task to locate and print it. This is sometimes accompanied by the theological belief that Providence would have preserved the sacred text without allowing a single original reading to be lost. One New Testament scholar cites the view that in dealing with the text of the New Testament conjecture tends to become “a process precarious in the extreme, and seldom allowing anyone but the guesser to feel confidence in the truth of its results.” [88] Metzger lays down such stringent requirements for a successful conjecture that the most likely one in the New Testament, in 1 Peter 3:19, fails in spite of its many attractions. [89] Such conservatism may arise less from a “distrust of critical judgment,” [90] than from a feeling of reverence toward the text, based on the premise of divine inspiration.

A further New Testament example occurs in 2 Peter 3.10. Many variants are recorded, none of which seems to be “original.” [91] The verse is dealing with the future apocalyptic destruction of the earth. The verse concludes:

καὶ γῆ καὶ τὰ ἐν αὐτῃ ἔργα εὑρεθήσεται.

... and the earth and the works in it shall be found.

Clearly something is not quite right here, although this reading has the best ancient external evidence in its favor. One early papyrus adds the word λυόμενα ‘dissolved’—except that the verb λύω is already used twice in the immediate context. Other ancient variants include ἀφανισθήσονται ‘will disappear’ and κατακαήσεται ‘will be burned up’. In addition scholars have conjectured the following:

... and the earth and the works in it shall be found.

πυρωθήσεται ‘will be burned’

ἐκπυρωθήσεται ‘will be burnt to ashes’

ἀρθήσεται ‘will be taken away’ and

κριθήσεται ‘will be judged’.

However none of these is printed in the Greek text—it is left with the virtually meaningless εὑρεθήσεται.ἐκπυρωθήσεται ‘will be burnt to ashes’

ἀρθήσεται ‘will be taken away’ and

κριθήσεται ‘will be judged’.

A corrective to this “hyper-conservative” view is achieved when we realize that one of its motivations really does appear to be a basic distrust of human critical judgment—the underlying and perhaps unconscious assumption that somehow anything that is “ancient” or even “old” is somehow bound to be more reliable than someone’s intelligent surmise. Tanselle stresses that the process of recensio is just as conjectural as that of emendatio (he appears to include examinatio as a part of recensio)—both procedures are based completely on human judgment. [92] Thus just as a recension can be good or bad, so can a conjecture. For an example of an unnecessary and indeed inappropriate conjecture, see the example from Plato’s Timaeus above. [93]

An example of a necessary and satisfying conjecture involves Housman’s emendation of Martial (Liber Spectaculorum 21.8) [94] :

haec tamen res est facta ita pictoria (mss.)

haec tantum res est facta παρ᾽ ἱστορίαν. (Housman)

‘This thing alone happened contrary to the story.’

The confusion of the last two words arose from misreading the Greek uncials as Latin:

haec tantum res est facta παρ᾽ ἱστορίαν. (Housman)

‘This thing alone happened contrary to the story.’

ΠΑΡΙϹΤΟΡΙΑ → ITAPICTORIA

This conjecture is all the more satisfying because it neatly fulfills the transcriptional requirement—that the correct reading be able to account for the origin of the corrupt reading. And of course it makes excellent sense—as well as possessing the “learned” feature of a Greek quote in the midst of a Latin poem.An enlightening (and humorous) account of how one scholar has made conjectures in Latin literature is provided by Robin Nisbet. [95] In his article Nisbet contrasts the need to “fiddle with the letters” in order to determine what the original must have been, [96] with the frequent need to “clutch out of the air a word with perhaps no more than a general resemblance to the transmitted reading.” [97]

A New Testament scholar, John Strugnell, [98] some years ago reacted against the entrenched conservative tendencies of his colleagues with an article entitled “A Plea for Conjectural Emendation in the New Testament.” [99] In this article Strugnell critically examines the reasons why NT scholars have been and continue to be so reticent about making or accepting conjectures into their editions of the NT text. Such reasons include the following: there is such a vast amount of evidence that the correct reading must survive somewhere (“wishful thinking”), the comparative excellence of the manuscripts (this is a petitio principii, i.e. an example of circular reasoning), the relative antiquity of manuscripts (but what about an early corruption that has affected the archetype?), and the belief that the archetype is identical to the autograph (an assumption that can never be proved).

Strugnell even suggests that it may at times be necessary to “correct the author himself”—a suggestion which runs counter to most editors, especially those of biblical texts. [100] He divides errors into two types: those of the author and those made subsequently—but of course we can never be sure which is which. [101] And each type is open to conjectural emendation if we are dissatisfied with the text as it stands.

Strugnell’s “plea” was answered by a fellow NT scholar, G. D. Kilpatrick, in 1981. [102] Kilpatrick, who does not appear to be against conjecture for the reasons given above, nevertheless is uncomfortable with Strugnell’s readiness to correct the author, and to the consequent opening the door to “considerable rewriting of the New Testament.” [103] In addition Kilpatrick suggests that the true dichotomy is not between conjectures and manuscript readings, for certainly some readings, even ancient ones, are themselves conjectures (presumably made by scribes); but between conjectures and non-conjectures. [104] He distinguishes between conjecture and deliberate change (by scribes) and characterizes a non-conjecture as a reading which, although not the original reading, is nevertheless derived from or a part of the transmitted text; while a conjecture, though “related” to the text, is not part of this transmitted text, nor derived from it. [105] He thus contrasts the uncertainty inherent in the (perhaps inspired) guesswork of the conjecture with the (implied) certainty of the transmitted text, and thus seems to be falling into the trap of allowing anything old to be of greater value than a modern intelligent and educated conjecture. I note that in the same volume in which Kilpatrick’s article appears there is also a paper discussing how modern translations of the New Testament deal with the problem of a corrupt text. [106] It appears that although a conjecture sometimes must be made in order to have a sensible English translation, nevertheless the conservatism of biblical editors keeps them from actually introducing many such conjectures into editions of their Greek texts. [107]

This degree of conservatism is rarely apparent among editors of classical texts. [108] Indeed, the earlier extreme divergence of opinions and the accompanying mutual hostility has, according to Richard Tarrant, in the past achieved “almost grotesque proportions” but has more recently settled into a calmer state. [109] Editors are now sometimes classified as “conservative” (more likely to follow the transmitted text) or “skeptical” (more inclined to emend the text) [110] ; the ideal is said to be that balance of conservatism and skepticism which leads one to “be as ready to preserve the transmitted text when it is sound as to emend it when it is defective.” [111] This ideal includes warnings against supposing that the transmitted text is only faulty when it is obviously so, balanced with the necessity of only altering an archetype when there is good reason to do so. [112] Tarrant further describes this optimal methodology negatively: not “is what we have intelligible?” (conservative), nor “is what we have the best conceivable?” (skeptical), but “is what we have the words in which this author would likely have expressed this meaning?” [113] Accurately answering this last question naturally requires a deep familiarity with the author’s style and patterns of thought, for which no mechanical shortcuts or formulaic approaches can substitute. [114]

I close this brief discussion on conjecture by mentioning that one of the most prolific and influential Homeric scholars of the past generation, M. van der Valk, has written frequently that the Alexandrian scholars who worked on the text of Homer, i.e. Zenodotus, Aristophanes, and Aristarchus, made their alterations to the Homeric text not by choosing one variant out of several which appeared in the manuscripts available to them, but rather by basing their decision on subjective reasons such as what is “appropriate”; they were merely “rewriting” Homer according to their own personal preferences. In the preface to his 1949 work on the Odyssey, van der Valk states bluntly that “the ancient critics are not to be trusted and have altered the original text in many places by making subjective conjectures.” [115]

In the next chapter I shall examine the different ways in which textual criticism has been applied to the Homeric text; I shall argue that the regular rules of textual criticism do not always “work” when dealing with Homer. I will also suggest that the Alexandrian scholars, far from exercising the kind of capricious subjectivity alleged by van der Valk, instead used manuscript evidence and an intelligent and educated sense of judgment in much the same way that a modern editor does. The question to be considered there will be: what is the significance both of the quantity, and more importantly of the quality, of the variant readings which have survived as witnesses to the text of Homer?

Footnotes

[ back ] 1. See Maas 1958:1; Renehan 1969:2; West 1973:8.

[ back ] 2. Reynolds 1983:406–407.

[ back ] 3. West 2001:88–129 lists more than 700 published papyri plus a further 850 or so that are thus far unpublished; in addition he includes about 140 papyri containing Homeric glossaries, commentaries, and scholia minora; also nearly 50 others containing quotations of lines from the Iliad. West further uses nineteen medieval minuscule manuscripts, some of which contain complete texts of the Iliad. T. W. Allen had listed a total of about 190 medieval manuscripts, and in his editio maior of 1931 he attempts to cite each for every variant reading, leading to a critical apparatus often taking up more space than the text itself.

[ back ] 4. Aland 1987:72–184; Metzger 1992:36–94; Epp and Fee 1993:4–6.

[ back ] 5. For a helpful account, which is written to describe the textual criticism of Latin texts but applies equally well to Greek, see Tarrant 1995:106f. See also Reynolds and Wilson 1991:207ff.

[ back ] 6. See below, n83.

[ back ] 7. For these and other Latin terms, see Appendix B.

[ back ] 8. Bengel 1742, Admonition 12 in his preface.

[ back ] 9. However, Reeve (1987:1ff.) argues, firstly, that it is impossible to prove that any particular manuscript is “exclusively derived” from another, and secondly, that so-called codices descripti, far from being inutiles, can be useful both for textual editors and also for shedding light on the history of the transmission of the text. See esp. p. 8.

[ back ] 10. An example of the avoidance of this principle involves the debate over the merits of the “King James Version” of the Bible. KJV proponents argue that the overwhelming preponderance in numbers of manuscripts supporting the “Textus Receptus” proves its superiority, whereas the majority of scholars point to a) the widespread dependence of these (late) manuscripts upon only a few exemplars, and b) the significant number of much earlier manuscripts whose text shows much less evidence of either contamination or the “smoothing out” of difficult passages. For a critique of the so-called “Majority Text” and of the arguments used to support it, see Epp and Fee 1993:183–208. For a modern and more nuanced defense, see Robinson 2002.

[ back ] 11. See Pfeiffer 1976:156f.

[ back ] 12. See Wolf 1985. Wolf’s translators discuss his debt to Eichhorn on pp. 18–26; and Wolf himself frequently makes comparisons between Homeric and Old Testament textual study, e.g. pp. 49–52.

[ back ] 13. Pfeiffer 1976:90.

[ back ] 14. See above, pp. 1–2.

[ back ] 15. See Metzger 1992:112.

[ back ] 16. Metzger 1971:154.

[ back ] 17. Metzger 1971:663.

[ back ] 18. Housman 1903:livff.

[ back ] 19. See variant b in the passage from Plato’s Timaeus, below, pp. 19–20.

[ back ] 20. Housman 1903:lixff.

[ back ] 21. Translation from Goold 1998.

[ back ] 22. Housman 1903:lx.

[ back ] 23. Goold 1988:xxxix. He is evidently using the term “interpolated” in a somewhat different sense from how I use it in chaps. 2 and following. Goold continues: “and none of the 60-odd manuscripts available inspires special confidence in its readings or permits us to ignore them.”

[ back ] 24. Translation from Smith 1992.

[ back ] 25. Ibid. One notes the type of dry humor inspired by encounters with textual corruption.

[ back ] 26. This is especially common in the Hebrew Bible, where an impossible form is regularly left in the body of the text, with a footnote presenting the correct form. Because in Hebrew vowels are treated as a sort of “overlay” to the consonants—and are thus not considered sacred, the correct vowels are written in the text in conjunction with the incorrect consonants, generally giving an unpronounceable form.

[ back ] 27. Another branch of the tradition passed down an intelligible but less helpful variant: ὁμοιότητι—Renehan (1969:48–49) characterizes this as a “conscious conjecture.”

[ back ] 28. See Appendix B. Also Horrocks 1997:67–70 and 102–105, who however does not use the term “itacism.”

[ back ] 29. Renehan 1969:48–49.

[ back ] 30. Zuntz 1946:212–213. This particular study was in reference to the text of 1 Corinthians and Hebrews. Cited in Epp and Fee 1993:128.

[ back ] 31. Epp and Fee 1993:14–15.

[ back ] 32. See Appendix B.

[ back ] 33. Reynolds and Wilson 1991:209.

[ back ] 34. See Speer 1995:394ff.

[ back ] 35. Tarrant 1995:112f.

[ back ] 36. Wolf 1985:43–45.

[ back ] 37. Housman 1903:xxxii, quoted in Tarrant 1995:111.

[ back ] 38. Tanselle 1995:21–22.

[ back ] 39. Reynolds and Wilson 1991:216–218.

[ back ] 40. Cf. Tanselle 1995:20, who discusses the “falsity of saying that ‘editorial insight is always less reliable than even the most unreliable documents.’ ”

[ back ] 41. Epp and Fee 1993:15, where the methods of one of the chief exponents of rigorous eclecticism, G. D. Kilpatrick, are criticized. In Black 2002:101–123, J. K. Elliott titles his chapter “The Case for Thoroughgoing Eclecticism” (my emphasis). One notes the suggestive labels given to these various positions.

[ back ] 42. As in the title of chap. 2 of Black 2002: “The Case for Reasoned Eclecticism” (pp. 77–100) by M. W. Holmes. Grenfell and Hunt 1906:75 (to be discussed further in chap. 3) recommend the use of “judicious eclecticism” in dealing with the unusual texts of the recently discovered Ptolemaic papyri of Homer.

[ back ] 43. See again Wolf 1985, who talks about the sense (internal evidence) and the authority (external evidence) of readings.

[ back ] 44. Westcott and Hort 1882:31; quoted in Epp and Fee 1993:127.

[ back ] 45. Quoted in Tarrant 1995:96; Tarrant’s translation of Bentley.

[ back ] 46. However, Bentley’s excesses in the practice of emendation are well known; for a humorous example of a “logical” but foolish emendation of a line of Horace, see Reynolds and Wilson 1991:186.

[ back ] 47. Tarrant 1995:107. Also his remark on the same page that “a stemma can describe only what is likely to be true in the majority of cases; it cannot overrule the critic’s judgment of any particular instance.”

[ back ] 48. See n55 below.

[ back ] 49. See Turner 1968. On pp. 49–51 Turner discusses papyri which were written outside Egypt and brought in subsequently: places of writing include Ravenna, Paphlagonia, and Rome; although the examples he discusses are documentary and not literary papyri, the possibility is always present that literary papyri as well could “travel” some distance from their place of origin.

[ back ] 50. See n26 above.

[ back ] 51. For the NT, I note the criticism in Epp and Fee 1993:42–44 and 94–96 of the “excessive” regard for the papyri of the NT held by Aland, as discussed in Aland 1987:56–64 and 83–95. Aland seems to use the age of these papyri (the earliest datable to 125 CE) to justify his view that they hold the key to the original text; Epp and Fee, however, point to the fact that all the papyri come from Egypt, and that it is most unlikely that texts from one location can be confidently accepted as representative of the NT text in general—especially as it is improbable that any of the originals were actually written in Egypt. Compare M. van der Valk’s modified version of a statement of Lehrs: “Thou shalt not fall on thy knees before the papyri,” in van der Valk 1964:532n6. Van der Valk uses this statement in support of his low view of the early papyri of Homer and other classical Greek authors such as Euripides.

[ back ] 52. The title of chap. four of Pasquali 1952. Already in 1882 Westcott and Hort (p. 31) had com-mented on the “occasional preservation of comparatively ancient texts in comparatively modern mss.”

[ back ] 53. Koester 1987:41. See also Benedict Einarson, in Renehan 1969:32: “Many of the variants in the text of the New Testament arose before these writings became canonical.” See Epp and Fee 1993:127 for criticism of this viewpoint.

[ back ] 54. Strugnell 1974:552.

[ back ] 55. Housman 1903:xl: after the work of recensio and examinatio are done, we have before us “an archetype ... corrupt and interpolated; and now begins the business of correcting this.”

[ back ] 56. Tarrant 1995:97.

[ back ] 57. In Denniston and Page 1957:xxxviii, for example, Page writes of the manuscript “cod. G” (of Aeschylus’ Agamemnon) that its value “could not be less than it is without entirely ceasing to exist.”

[ back ] 58. A good example of a manuscript which has been carefully “collated,” leading both to “corrections” and to the recording of variants in the margins, is the medieval Iliad manuscript Venetus A, on which more will be said elsewhere in this book.

[ back ] 59. See Tarrant 1995:108ff.

[ back ] 60. See Reynolds 1983:435.

[ back ] 61. Koester 1987:40–41.

[ back ] 62. In the next chapter I discuss T. W. Allen’s attempts at creating stemmata for the Homeric manuscript evidence.

[ back ] 63. It should also be pointed out that papyri generally defy the whole concept of stemmatics, in that they invariably antedate the hypothetical archetype—which is usually presumed to date from the Byzantine period and to be the source of the medieval manuscript tradition.

[ back ] 64. Maas 1958, English translation of his 1950 German edition.

[ back ] 65. Pasquali 1952.

[ back ] 66. West 1973.

[ back ] 67. Reynolds and Wilson 1991:288–289. They also here defend Maas (op. cit., n1) against the charge that he underestimated the importance of contaminatio. See also Tarrant 1995:108f.

[ back ] 68. Quoted in Epp and Fee 1993:11–12.

[ back ] 69. West 1973:7–9. As he himself states, his book improves on that of Maas (above, n1) in that it discusses contamination of manuscripts, which Maas had only briefly mentioned.

[ back ] 70. See n1 above.

[ back ] 71. This example, and several others, are given in Reynolds and Wilson 1991:223–233.

[ back ] 72. See a good discussion in Renehan 1969:68–69.

[ back ] 73. To use M. L. West’s words (West 1973:41–42).

[ back ] 74. See Renehan 1969:63–65.

[ back ] 75. Ibid.

[ back ] 76. Ibid. In Timaeus 75E we find τὸ δὲ λόγων νᾶμα, ‘the stream of speech’.

[ back ] 77. See Appendix B.

[ back ] 78. See above, p. 10, for the distinction.

[ back ] 79. West 1973:8.

[ back ] 80. Tarrant (1995:119) quotes D. R. Shackelton Bailey, who in describing the process of emendatio, mentions the “touchstones which knowledge and experience automatically apply.”

[ back ] 81. OED s.v. “conjecture” 4; “emendation” 2.b.

[ back ] 82. Tarrant 1995:118. In a private communication he suggests that “emendations are conjectures that have been run up the flagpole and have garnered a sizable number of salutes.”

[ back ] 83. Ibid.

[ back ] 84. Quoted in Renehan 1969:104.

[ back ] 85. Metzger 1992:184.

[ back ] 86. Strugnell 1974:543.

[ back ] 87. Strugnell 1974:543.

[ back ] 88. Greenlee 1964:15, quoting Frederic G. Kenyon.

[ back ] 89. Mss. ἐν ᾧ καί; conjectures: Ενωχ [Enoch] καί and ἐν ᾧ καὶ Ενωχ; see Metzger 1971:693; also Metzger 1992:182–185. “[The successful conjecture] must not just satisfy the tests of the correct variant, but it must satisfy them absolutely well ... its fitness [must be] exact and perfect ... The only criterion of a successful conjecture is that it shall approve itself as inevitable.”

[ back ] 90. See n38 above.

[ back ] 91. Metzger 1971:705–706.

[ back ] 92. Tanselle 1995:20.

[ back ] 93. Pp. 19–20.

[ back ] 94. See Renehan 1969:46–47. The actor playing Orpheus was killed by a bear during a performance of the Orpheus legend.

[ back ] 95. Nisbet 1991.

[ back ] 96. Ibid., 72.

[ back ] 97. Ibid., 66. On p. 91 he suggests that, for making conjectures, “The period after Christmas is particularly productive, when everything is shut and one is slouched in an arm-chair half-asleep.”

[ back ] 98. Strugnell was also heavily involved with the original editing and publishing of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

[ back ] 99. Strugnell 1974.

[ back ] 100. Cf. the precept that an editor “will not hesitate to correct the archetype but never venture to correct the author,” quoted in Tarrant 1995:118.

[ back ] 101. Renehan (1969:22–23) gives an example from Eustathius where he thinks it quite possible that the error originated with the author.

[ back ] 102. Kilpatrick 1981.

[ back ] 103. Ibid., 357–358.

[ back ] 104. Ibid.

[ back ] 105. Ibid., 358–359.

[ back ] 106. Rhodes 1981.

[ back ] 107. See above, pp. 24–25.

[ back ] 108. Although Nisbet (1991:88) imagines that his conservative critics may accuse him of cacoethes coniciendi, which phrase then leads him to make a further conjecture.

[ back ] 109. Tarrant 1995:119–120.

[ back ] 110. Tarrant 1989:124 cites the extreme case of an editor of Euripides who, in his readiness to excise supposedly “interpolated” lines, worked “on a principle somewhat like that of the provincial English dentist—‘if you won’t miss it, why not have it out?’ ”

[ back ] 111. Ibid.

[ back ] 112. Ibid.

[ back ] 113. Ibid.

[ back ] 114. Nisbet (op. cit.) exemplifies this familiarity with his authors, as does Housman (op. cit.).

[ back ] 115. Van der Valk 1949:9. The phrase “subjective conjecture” is one of his favorites.