-

Graeme D. Bird, Multitextuality in the Homeric Iliad: The Witness of the Ptolemaic Papyri

Introduction

1. Textual Criticism as Applied to Biblical and Classical Texts

2. Homer and Textual Criticism

3. The Ptolemaic Papyri of the Iliad; Evidence of Eccentricity or Multitextuality?

Appendix A

Appendix B

Bibliography

Chapter 3: The Ptolemaic Papyri of the Iliad: Evidence of Eccentricity or Multitextuality?

Until the end of the nineteenth century, the text of Homer, as preserved in papyri and medieval manuscripts, was relatively uniform, with few significant variant readings to exercise scholars. True, there were instances where an ancient author such as Plato or Aeschines had quoted a passage of Homer in a way that differed in unusual ways from the "received text," but these cases were generally put down to the faulty memory of the author.

When, however, in 1890 the first Homeric papyrus dating to the Ptolemaic period (P8, containing Iliad XI 502–537) was discovered by W. M. Flinders Petrie [1] in Gurob in Egypt and published in 1891 by J. P. Mahaffy, [2] it was found to contain a surprisingly different version of the text: four lines not in the "vulgate" (labeled according to current convention as 504a, 509a, 513a, and 514a), one "missing" line (either 529 or 530), and some significant variation within two existing lines (515 and 520). Further, S. West notes that the variation in line 515 is directly related to the "insertion" of the previous line, 514a. [3] This exemplifies the fact that many "plus verses" are not just "interpolated" randomly into the text; rather they tend to fit "organically"—the surrounding context frequently gives the appearance of having been "modified" to allow them to fit better. [4]

As discussed earlier, [5] the manuscripts of Homer may be divided into two basic and broad groups, based on age and the type of material used: papyrus and parchment. However, I note the two following (not necessarily helpful) conventions: the term "papyrus" is taken to mean "any ancient manuscript, whether or not it is written on papyrus," whereas the term "manuscript" means "medieval manuscript." [6] The first of these conventions helps to explain why, for instance, the very first item in the standard list of "papyrus manuscripts" of the Iliad, viz. P1 ("codex Ambrosianus," dated 5th–6th century CE), is actually written on parchment (as are P89, [7] P162, and P233). A few further "papyrus" documents, all originally school exercises, are of other materials: limestone inscriptions (e.g. P107, P108, P110 and P121), ostraka (e.g. P137, P161, P263, P522, and P525) and wooden tablets (P131 and P164). [8]

Further complicating matters regarding papyrus identification, as the number of "papyri" has grown, the numbering system has been modified somewhat: starting with (for the Iliad) T. W. Allen's original P1–P122, [9] the list currently extends as far as P1569 in Martin West's 2001 study, which correlates closely to his 1998 and 2000 Iliad editions. West (following Sutton) includes two further categories: first, ancillary documents such as glossaries and scholia minora, notated h1–h142 (the h stands for "Homerica"); second, non-Homeric papyri containing Homeric quotations; these are labeled w1–w47 (the w stands for "witness"). [10]

It happens that the distinction between the terms "papyrus" and "manuscript" coincides with a division both of date and of writing style: virtually all the "papyri" date from between the fourth/third century BCE and the eighth century CE, whereas almost all the "manuscripts" are dated from the ninth to the eighteenth centuries CE; similarly, the uncial form of writing is exclusively used on all documents until it is superseded by minuscule script around the ninth century CE. The other major change which takes place is that from roll (or scroll) to codex: rolls tend to die out around the end of the 4th century CE, and codices, whose use begins early in the 2nd century (or perhaps earlier), quickly become the standard vehicle. [11]

I illustrate these features in simplified diagrammatic form:

| 4th/3rd cent. bce–8th cent. ce | 9th cent. ce–18th cent. ce |

|---|---|

| papyrus | parchment |

| uncial script | minuscule script |

| scroll/roll and codex | codex |

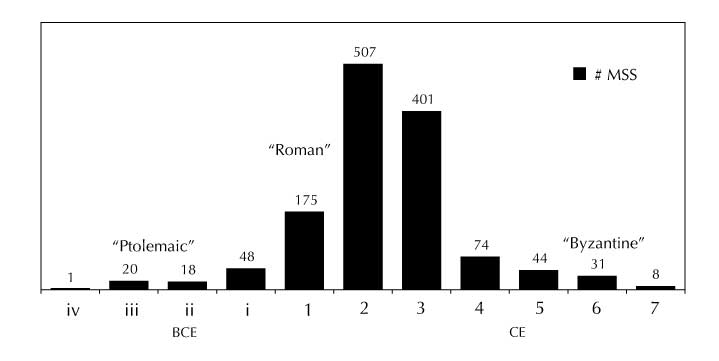

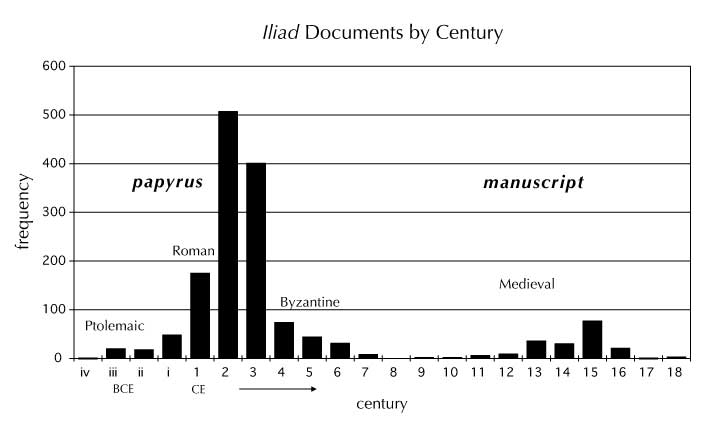

The earliest Iliad papyri date from the fourth/third century BCE, with at present 17 papyri from this period. At the other end of the chronological scale are 27 papyri from the sixth and seventh centuries. Thus Iliad papyri span roughly a thousand-year period, from the "Ptolemaic," through the "Roman," and into the "Byzantine" periods. Chart 1 illustrates the distribution of those papyri of the Iliad which can be dated (more than four-fifths of the total). One immediately notices the "normal" (in a statistical sense) shape of the graph, indicating among other things the scarcity of Ptolemaic (6 percent) and late Byzantine papyri (12 percent), as well as the relative abundance of Roman texts (82 percent). Whatever the factors responsible for this state of affairs, our examination of the Ptolemaic papyri must bear in mind that our surviving amount of evidence is tiny, and cannot automatically be assumed to be a "representative sample." However, neither can its evidence be ignored. I add for comparison Chart 2, which includes the medieval manuscripts along with the papyri.

Chart 1. Chronological distribution of Iliad papyri, by century.

Chart 2. Chronological distribution of Iliad papyri and manuscripts, by century.

Note the far smaller number of these later witnesses to the text; however, what the chart does not show is that the medieval manuscripts each contain on average far greater amounts of Homeric text; in contrast, some of the papyri are extremely fragmentary, containing sometimes only a few partial lines.

In addition to the more than 1,500 "papyri" of the Iliad mentioned above, plus the 142 "Homerica" and the 47 "witnesses," there are 190 medieval (non-papyrus) manuscripts, [15] dating from the ninth to the eighteenth centuries CE.

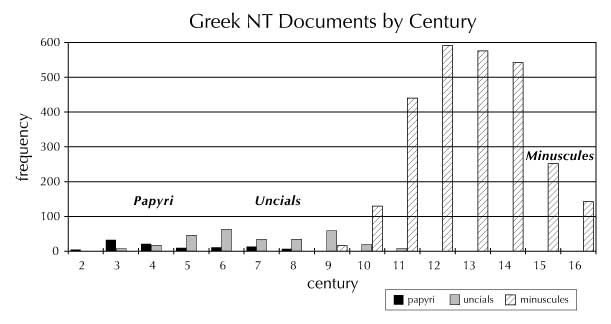

Chart 3. Chronological distribution of Greek New Testament papyri and manuscripts, by century.

The oldest is "X" (not known to Allen), dated to the ninth century CE, and containing portions of text along with an interlinear prose paraphrase. The earliest complete text of the Iliad is the famous Venetus A (Marcianus 454, tenth century), [16] and the latest is U12 (not listed by West), dated to 1752, containing 5 books of the Iliad, and "not collated." [17] This gives a total of approximately 1,900 [18] surviving documents which bear direct witness to the text of the Iliad, with a span of approximately two thousand years.

Finally, as previously mentioned, we have the evidence of the scholia, the classical and post-classical quotations, [19] so-called "allusions"—references to the Homeric text that are not actual quotations but nevertheless indicate a familiarity with the Homeric text [20] —vase paintings, [21] and inscriptions such as those on the Dipylon Vase and "Nestor's Cup." [22]

Of all classical literature Homer, and specifically the Iliad, is represented by the largest quantity of manuscript evidence. This is because Homer was read more than any other classical author, both in schools and by the reading public. As I have already noted above, the situation for the Greek New Testament is comparable to that of Homer. I illustrate the manuscript data for the GNT in Chart 3, [23] which makes for an interesting comparison with Chart 2. The fact that these two charts are virtually mirror images of each other indicates a lot about the very different circumstances of the transmission of the two texts.

I move now to a closer examination of the Ptolemaic papyri of the Iliad. The term "Ptolemaic papyri" refers collectively to a group of papyrus manuscripts possessing a common location of discovery and datable to a common period. The general location is Egypt, and the period is that roughly covering the reigns of the first eight Ptolemies—from Ptolemy I Soter, who ruled from 305/304 to 283/282, to Ptolemy VIII (Euergetes II), who ruled intermittently, as well as both solely and jointly, between 170 and his death in 116. There appears to have been some sort of turmoil around the year 146/145, when Ptolemy VIII returned from Cyrene to Egypt and overthrew and killed his nephew Ptolemy VII (Neos Philopator). Included amongst the events of that troubled time was the expulsion from Alexandria of the grammarians, including Aristarchus of Samothrace, of whom more will be said. This date, 146 or 145 BCE, is often considered the end of the Ptolemaic period as far as the "eccentric" papyri are concerned, for reasons which will be discussed; however Grenfell and Hunt state that the Ptolemaic period ends in 30 BCE, as in the listing below: [24]

| Ptolemaic | before 30 BCE |

| Roman | 30 BCE–284 CE |

| Early Byzantine | 284–400 CE |

| Late Byzantine | after 400 CE |

For the purposes of this chapter, I use the following simplified scheme for manuscripts (papyrus or otherwise):

| Ptolemaic | iii–i (i.e. third to first centuries BCE) |

| Roman | I–III (i.e. first to third centuries CE) |

| Byzantine | IV–VIII (i.e. fourth to eighth centuries CE) |

In this chapter I will note the significance of the date 146/145, while also considering papyri that date as late as the end of the first century BCE.

The Ptolemaic papyri of Homer, the first of which [25] was published in 1891 and the most recent [26] in 1984, aroused a great deal of excitement when they first saw the light, evoking various reactions and theories from scholars; some of these theories did not last long, while others are still held today. Descriptions of the painstaking work involved, the frustration of finding a tiny fragment of some work, and the knowledge that the vast majority of fragments are forever lost, make compelling reading and cause one both to admire the diligence of these early explorers, and to value more highly those pieces which do survive.

Almost all surviving classical papyri (and those of the Hebrew Bible and the Greek New Testament) come from Egypt, south of the Delta, where the rainless climate favors their survival. [27] In general the vast majority of papyri come from ruined buildings and from the rubbish dumps of villages in Upper (i.e. southern) Egypt. [28] Some have been found in tombs, some were buried in jars, and some have been extracted from the wrappings of mummies. Those papyri that fall into this last category bear the description "cartonnage." J. P. Mahaffy describes how at one of the sites, Gurob, coffins were "made of layers of papyrus, torn into small pieces, and stuck together so as to form a thick carton, painted within and without with designs and religious emblems." [29] The man who discovered the first Ptolemaic papyrus of Homer, Flinders Petrie, detected in the structure of these cartons the use of discarded documents, and began the task of separating and cleaning the fragments. Difficulties included the fact that often chalk had been used to draw on the surface of the papyrus, thereby destroying the ink; also worms would bore into the papyrus in search of the glue which was used to join papyrus strips; and sometimes "soaking the fragments in water releases a substance which irreparably stains what is left of any writing on the papyrus." [30]

The names of Grenfell and Hunt, who discovered more Ptolemaic papyri of Homer than anyone else (including the "eccentric" P7, P12, P40, and P41), are almost synonymous with papyrological discovery. They too give an account of some of their experiences, an account which underlines the tenuousness of the element of chance in searching for and finding papyrus documents. [31] The mummies, wrapped in cartonnage made out of papyrus fragments, were buried anywhere from a few inches to several feet below the surface of the ground. In some of the deeper cases, the original burial sites were covered with a layer of debris from the Roman period. For such papyrus fragments to survive, there had to be a total lack of moisture; and since we are dealing with a desert, through the middle of which flows a river (the Nile), all towns and villages were (and largely still are) very close to the water. We have the paradoxical situation of the Nile being the place where all the papyri are located, but also being one of the greatest threats to their survival. Thus a large amount of papyrus material will have been lost due to moisture damage, and Grenfell and Hunt comment on this in their account. [32]

In addition to staying dry for well over two thousand years, the papyri had to have escaped plundering, both ancient and modern, by local inhabitants and looters. In their search for more valuable artifacts, these "explorers" originally discarded cartonnage as being of no value, and only later learned that it was to their advantage to preserve it. In some cases the "locals," all too aware of the value of individual fragments, would even separate pieces of papyrus so as to sell them separately for more money than the original larger piece would have fetched. [33] Thus a significant part of the process of editing a papyrus consists of deciding which pieces come from the same original manuscript, and then attempting to join or at least locate such pieces in their original position—rather like a jigsaw puzzle for which only a fraction of the pieces are available. For example, Stephanie West's edition of P12 (the longest Ptolemaic papyrus of Homer) consists of at least thirty "large" recognizable pieces, plus more than forty smaller, unidentifiable fragments. [34]

Provenance is not always easy or even possible to determine; Grenfell and Hunt remark that some of their papyrus fragments came to them by means of a dealer, far from where they had been unearthed, while others they uncovered themselves. Opposite is a table showing the number of papyri of the Iliad for which the provenance is fairly certain (373 out of about 1,900, or approximately one-fifth). I separate the Ptolemaic papyri from the rest; note the importance of Hibeh, thanks in large part to the team of Grenfell and Hunt.

Even in cases where the provenance is known, one cannot be sure that the papyrus was actually written there. Either the papyrus or the mummy (or both) could have been transported from elsewhere. External evidence is thus often lacking, but on occasion an intact mummy contains a datable and/or locatable fragment; this is of great assistance in dating/locating other fragments attached to the same mummy. Sometimes a group of mummies found in close proximity contain parts of the same papyrus document. [35] Mahaffy describes how he (along with Petrie and A. H. Sayce) was "arrested and sur-prised" to find that the papyrus fragments they were cleaning and deciphering included legal documents which mentioned, instead of the expected late Ptolemies or Roman emperors (as in previously found documents), the names of the second and third Ptolemies—i.e. the materials could be dated no later than 220 BCE, and therefore the classical texts mixed up with these documents were themselves most likely to be of such an early date. [36]

Numbers of Iliad Papyri with Secure Provenance

| Site | Ptolemaic | Later | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxyrhynchus | – | 200 | 200 |

| Fayum | 31 | 33 | |

| Hermupolis | – | 28 | 28 |

| Tebtunis | 4 | 20 | 24 |

| Soknopaiou Nesos | – | 10 | 10 |

| Hibeh | 8 | 1 | 9 |

| Karanis | 1 | 8 | 9 |

| Madinet Madi | – | 9 | 9 |

| Theadelphia | – | 7 | 7 |

| Thebes | – | 7 | 7 |

| Gurob | 1 | – | 1 |

| El Lahoun | 1 | – | 1 |

| Magdola | 1 | – | 1 |

| other | – | 34 | 34 |

| totals | 18 | 355 | 373 |

Grenfell and Hunt conclude that in the case of the Hibeh papyri, much of the material for the cartonnage originated from a library of classical literature, probably belonging to a Greek settler at Oxyrhynchus, which is some thirty to forty miles southwest of Hibeh, on the opposite (west) bank of the Nile. [37]

It needs to be stressed that Homeric Ptolemaic papyri make up only a tiny fraction of the total papyri of the Ptolemaic period—the majority are administrative documents, and several are of other classical authors. Some are obviously classical and literary but so far not identified as to author. Nonetheless our small numbers of Homeric papyri, when used with proper precautions (to be discussed below), are invaluable for the light they shed on the text of Homer at this period and, I hope to argue, at earlier times as well. [38]

As mentioned above, the discovery of the Ptolemaic papyri of Homer aroused great curiosity and excitement initially. By the year 1897 the following Iliad papyri had been unearthed, all dating to the third century BCE:

| Papyrus | No. Lines | "New" Lines | Percent | Provenance | Discoverer | Date* | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P8 | 36 | 5 | 13.9% | Gurob | F. Petrie | 1891 | cartonnage |

| P5 | 72 | 9 | 12.5% | ?? | J. Nicole | 1894 | ?? |

| P7 | ~90 | 31? | 34.4% | Hibeh | G. & H.** | 1897 | cartonnage |

| P12 | ~282 | 27? | 9.6% | Hibeh | G. & H. | 1897 | cartonnage |

| P41 | 73 | 1 | 1.4% | Hibeh | G. & H. | 1897 | cartonnage |

*This is the date of publication, not necessarily of original discovery.

** Grenfell and Hunt 1906.

The column labeled "percent" is calculated by dividing the number of new lines by the number of lines in total—i.e. dividing column 3 by column 2. Thus for P7 one can see that 33%, or approximately 1 in 3 of its lines are "new"—i.e. not in our "usual" text of Homer.

T. W. Allen, [39] reviewing (favorably) Arthur Ludwich's Die Homervulgata als voralexandrinisch erwiesen (Leipzig 1898), describes how until 1891 the manuscripts of Homer were fairly homogeneous, presenting the "vulgate," although contrasting at times with each of the other two types of evidence, viz. the scholia and the quotations. Then between 1891 and 1897 the five papyri listed above were discovered, with their "remarkable variants," in particular additions to the "ordinary" text.

Two theories were initially put forward: [40] first, that the Ptolemaic papyri represent the pre-Alexandrian state of the text, which became the vulgate through the work of Zenodotus et al. This was soon shown to be untenable, as the Alexandrians' readings seldom coincide with the text of the "vulgate." The second theory suggested that the Ptolemaic papyri prove that the vulgate cannot yet have been in existence, but rather that there were several versions of the text in varying degrees of circulation. Ludwich's own theory, as his title indicates, was that our "vulgate" in fact dates back to a pre-Alexandrian date.

Allen also warns us in this article not to be overly impressed by the striking nature of the "plus verses," because of the extremely tiny size of the corpus (see below). Nevertheless, Allen considers the chief advance to be that "the Ptolemaic papyri do confirm the quotations" (Allen's emphasis)—i.e. classical authors such as Plato (2nd Alcibiades) and Aeschines (Against Timarchus) seem now not to have been quoting from a faulty memory, and critics who in the past felt justified in disregarding such quotations were now forced to look at them in a more serious light. In two cases (out of the then-extant Ptolemaic fragments), Plato and Aeschines can be shown to have quoted from extant versions of the text rather than from an imperfect recollection of the "original." [41] Similarly, because of supporting evidence in the Ptolemaic papyri, Allen pronounces that "Plutarch's accuracy is therefore vindicated; he verified his references," and hence "it must follow that quotations are to be treated with more respect than heretofore." Allen uses the term "eccentric" in this article—in a later work he claims to be the first to have done so. [42]

I note here the caveats of two scholars concerning the chance nature of what survives and what has perished. In the 1899 article just discussed, T. W. Allen warned that much of what survives in the way of papyrus material has been subject to the capriciousness of chance; since at that time there were so few (although the number was regularly increasing) Ptolemaic papyri of Homer, he cautioned against making confident assertions about how things were, based on the slim body of evidence. [43] In another place he mentions the "capricious evidence," and asks rhetorically, "Herodotus in 11 quoted lines (from different places) has no additional lines, but what if he had quoted 100 continuous lines?" [44] In a similar vein Turner warns of the "element of chance" regarding what has been discovered, and where. Just because no papyri have been found at Alexandria, one should resist the temptation to conclude that there never were any. "The case of Alexandria illustrates the unpredictability of papyrus evidence. Almost anything may turn up, yet what is expected often does not seem to. From such finds one may argue positively but not negatively: the argument from silence is especially dangerous." [45]

As I have discussed frequently in this book, most scholars appear to work from the assumption that there was an "original" text of the Iliad, from which manuscripts such as the Ptolemaic papyri "deviated" more or less significantly; therefore terms such as "correct" and "incorrect" or "genuine" and "spurious" are frequently encountered in the literature dealing with textual matters. In Chapter Two I examined this and similar assumptions; at this point I notice how West herself deals with the unusual variations presented by the Ptolemaic papyri. These variations include both significantly different versions of the same line, and—the most unusual feature, and the one which gave rise to descriptions such as "wild" and "eccentric"—the so-called "additional lines" or "plus verses." As Stephanie West states in her introduction, these variants "cannot be explained by the processes of merely mechanical corruption." [46] In the case of an author whose work was written down from the start, one usually has to assume such "processes of mechanical corruption"—the study of which involves application of the science of textual criticism, discussed in Chapters One and Two.

In her preface, West does appear to be "neutral" regarding the Ptolemaic variants:

The textual criticism of the Homeric poems is perpetually bedevilled by the metaphysics of the Homeric question. It may be no more than wishful thinking to suppose that in any particular case we can arrive at the word or phrase chosen by the monumental composer: perhaps terms like "original" and "authentic" are only relative. For this reason I have often been non-committal, perhaps even cursory, in discussing the variants offered by these papyri. [47]

Further on, in her introduction, she states

With regard to the "plus verses," so frequent in these papyri:

Here West seems to be torn between the conventional view that lines can be either "genuine" or "interpolated," and the view for which I am arguing in this book, namely that such "additional" lines may indeed be "authentic"—i.e. composed and performed in the oral tradition, and recorded in some texts and not others, because performed on some occasions and not on others. However, West finally concludes,

As one reads through West's text and commentary, one frequently comes across the following characterizations of papyrus variants (this is only a sample): [51]

There is no evidence that ... [there was] anything abnormal about these texts; ... Plato and Aeschines ... used very similar texts. [48]

There remains a large number of lines for which no close parallel can be found: some of these may have been composed for interpolation, but it is equally possible that they come from lost hexameter poetry. [49]

The relatively minor scale of the interpolations argues against the view that there is a connection between the eccentricities of the early texts and the long oral tradition of the poems, except insofar as the rather discursive style suitable for oral technique attracted interpolation. [50]

| I 108 | the papyrus' reading is "not inferior." |

| I 567 | the papyrus' reading is "not an aberration." |

| II 622 | the papyrus variant is "not formulaic, may be right." |

| II 795 | the papyrus reading is "superior." |

| XI 271 | both readings [i.e. papyrus and "vulgate"] seem "equally good." |

| XII 180 | the papyrus reading "is not derived from the vulgate," i.e. it is "independent." |

| XII 183 | a [52] it is "very tempting to regard the text of the papyrus as authentic." |

| XII 192 | the papyrus "may well preserve an earlier version of this line." |

However, one also meets this kind of evaluation:

| XXI 406 | the papyrus presents a "rather stupid variant." |

| XXI 412 | the papyrus' reading is "worthless." |

The point of mentioning these examples is to show that, in spite of appearing to be working from the assuption of one "original" and "genuine" text of the Iliad, West is still willing at times to allow for the "authenticity" of a papyrus reading, and even for the equal value of more than one variant. I argue later in this chapter that one can and should go further, showing that there are many cases where both the papyrus and the "vulgate" reading (and sometimes the reading of Zenodotus or Aristarchus as well) can be demonstrated—often by both internal and external evidence—to be "authentic," i.e. that the passage is "Homeric" whichever variant is read.

I note here briefly the views of some other scholars regarding the usefulness or otherwise of the Ptolemaic papyri of Homer. M. van der Valk, in his chapter dealing with the Homeric papyri, writes that most modern critics take the view that especially the early Ptole-maic papyri make it clear that originally, in the fourth and third centuries BCE, the Homeric text was uncertain and different versions of it existed. [53]

Van der Valk himself, however, is convinced that "in most instances the papyri are wrong over against the mss." [54] In suitably dramatic language he proclaims his lonely and lowly [55] position amidst a host of scholars who seem all too ready to "fall on th[eir] knees before the papyri." [56]

E. G. Turner [57] notes the view (held by, for example, G. Jachmann) that some "plus verses" actually improve the Homeric style of the passage (e.g. Iliad XII 189–193). He points out that this type of divergence cannot be put down to "mere carelessness by the scribe," but adds that it reflects rather "a lack of respect for the accurate recording of an author's words." He contrasts this attitude—that the exact words of an author are not sacred and hence do not need to be copied verbatim—with the later Roman mindset that encouraged more of a "respect for the authority of the text," a respect which he largely credits to the Alexandrians. [58] And yet he allows for the good textual basis of at least some of these "wild" papyri, warning us not to dismiss them as "the property of uneducated immigrants and untypical. They are beautiful examples of calligraphy, and they contain good readings as well as a high coefficient of error and a high proportion of change." [59] So Turner also, like West, is willing to grant some value to the readings of these papyri, while still insisting that much of their variation is due to what might called today a "fast and loose" approach to the text.

G. S. Kirk [60] and R. Janko [61] take basically the same view as S. West, and also (like van der Valk) minimize the value of the work of the Alexandrians in their efforts to find the "original" text of Homer. Taking a contrary position is G. Nagy, who attributes significant value both to the readings of the Ptolemaic papyri and to the work of the Alexandrian scholars. [62]

As mentioned above, one of the most unusual features of the Ptolemaic papyri, and the one which aroused the most interest when the documents were first discovered, is that of the "plus verses," i.e. the relatively large number of cases where extra lines appeared to be inserted into otherwise familiar passages of the Iliad and Odyssey. By way of illustration, I include on the next few pages a set of tables showing the frequency of "plus verses" in papyri from the fourth/third to the first centuries BCE, i.e. during the Ptolemaic period. The data are taken from T. W. Allen, [63] with my corrections, and additions from S. West, [64] D. F. Sutton, [65] and M. L. West. [66] The datings are approximate, based on paleographical criteria as well as the external evidence of datable documents discovered in close proximity to the papyrus in question. In some cases the total number of lines or the number of new lines ("plus verses") is uncertain as a result of the poor condition of the papyrus fragment. In addition S. West lists many fragments that cannot with any degree of certainty be matched up with an existing Ptolemaic papyrus; there is always the possibility that more "plus verses" or other significant variants are lurking just behind the scenes.

"New" Lines in the Ptolemaic Papyri of the Iliad

4th/3rd century BCE

| Papyrus | Book(s) | No. lines | "New" lines | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| w38* | 24 | 2 | 0 | – |

| P5 | 11–12 | 72 | 11 | 15.3% |

| P7 | 8 | 90 | 32 | 35.6% |

| P8 | 11 | 36 | 4 | 11.1% |

| P12 | 21–23 | 282 | 28 | 9.9% |

| P59 | 16 | 6 | 0 | – |

| P410 | 6 | 4 | 0 | – |

| P432 | 11–12 | 64 | 14 | 21.9% |

| P480a | 6 | 13 | 3 | 23.1% |

| P496 | 12 | 31 | 0 | – |

| P501c** | 17 | 17 | 4 | 23.5% |

| P672 | 17 | 15 | 1 | 6.7% |

| h59*** (quotation) | 6 | 8 | 0 | – |

| h117^ (anthology) | 3 | 6 | 2 | 33.3% |

| h125^^ (quotation) | 2 | 9 | 0 | – |

| w14^^^ (quotation) | 2, 5, 9, 13 | 8? | 1? | 12.5% |

| w19 (commentary) | 4, 5, 14 | 3 | 0 | – |

| Totals | 666 | 100 | 15.0% |

* This is the only fourth-century papyrus: it quotes 2 lines of Iliad XXIV as Orpheus.

**P501c is dated by Sutton and West as "Ptolemaic."

*** Previously labeled P317.

^Previously labeled P. Mich. 5.

^^ Previously labeled P459.

^^^Previously labeled P. Hamb. 137.

3rd–2nd century BCE

| Papyrus | Book(s) | No. lines | "New" lines | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P40 | 2–3 | 95 | 14 | 14.7% |

| P269 | 1 | 26 | 1 | 3.8% |

| P391 | 3 | 10 | 0 | – |

| P494 | 10 | 16 | 0 | – |

| P590 | 7 | 13 | 0 | – |

| P593 | 8 | 15 | 0 | – |

| P662 | 19 | 5 | 0 | – |

| h103 | glosses | – | – | – |

| Totals | 180 | 15 | 8.3% |

2nd century BCE

| Papyrus | Book(s) | No. lines | "New" lines | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P41 | 3–5 | 73 | 1 | 1.4% |

| P37 | 2 | 116 | 0 | – |

| P53 | 1 | 12 | 2 | 16.7% |

| P217 | 12 | 90 | 8 | 8.9% |

| P266 | 1 | 8 | 0 | – |

| P354 | 1 | 45 | 2 | 4.4% |

| P460 | 2 | 14 | 0 | – |

| P609 | 10 | 30 | 1 | 3.3% |

| h68 (commentary) | 9 | 19? | 0 | – |

| h102 (lexicon) | – | – | – | – |

| w21 (quotation) | 4 | 1 | 0 | – |

| Totals | 408 | 14 | 3.4% |

2nd–1st century BCE

| Papyrus | Book(s) | No. lines | "New" lines | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P102 | 5 | 15 | 0 | – |

| P270 | 6 | 297 | 0 | – |

| P271 | 22 | 52 | 0 | – |

| P333 | 1 | 13 | 0 | – |

| P671 | 16 | 35 | 0 | – |

| h88 (anth./summary) | 18–19 | – | – | – |

| Totals | 412 | 0 | 0.0% |

1st century BCE

| Papyrus | Book(s) | No. lines | "New" lines | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P13 | 23–24 | 1,069 | 3 | 0.3% |

| P29 | 2 | 9 | 0 | – |

| P45 | 23 | 15 | 0 | – |

| P47 | 13 | 179 | 0 | – |

| P51 | 18 | 13 | 5 | 38.5% |

| 30 other papyri | ~900 | 0 | – | |

| Totals | ~2,100 | 8 | 0.4% |

1st century BCE–1st century CE

| Papyrus | Book(s) | No. lines | "New" lines | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 papyri | 440 | 0 | – | |

| Totals | 440 | 0 | 0.0% |

I summarize by giving figures again for each of the six time periods:

| Century | No. lines | "New" lines | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4th/3rd | 666 | 100 | 15.0% |

| 3rd–2nd | 180 | 15 | 8.3% |

| 2nd | 408 | 14 | 3.4% |

| 2nd–1st | 412 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 1st | ~2,100 | 8 | 0.4% |

| 1st BCE–1st CE | 440 | 0 | 0.0% |

As one surveys the tables, the general trend is clear: papyri at the beginning of the Ptolemaic period show a distinct tendency to contain "additional" lines; this tendency diminishes as we proceed from the fourth/third century until we reach the period BCE/CE, when, apart from two papyri (P13 and P51), the "plus verse" phenomenon has virtually disappeared. The departure of Aristarchus from the library at Alexandria (around 146/145 BCE) roughly coincides with the virtual disappearance of the "plus verses"; these two events are generally believed to be related. Although this date (146/145 BCE) does indeed appear to be a terminus, two papyri of the first century BCE contain "plus verses, "and two additional papyri of this period (P53 and P354) are considered "eccentric" by S. West because of significant variants. [67] Conversely, she lists 22 "Vulgate Ptolemaic papyri" of the Iliad (in an appendix on pp. 283–284). However all of these date from after 150 BCE. So it appears that all Iliad papyri which date before 150 CE have "eccentricities" of some sort—unusual variants and/or "plus verses"—while very few later than this date do.

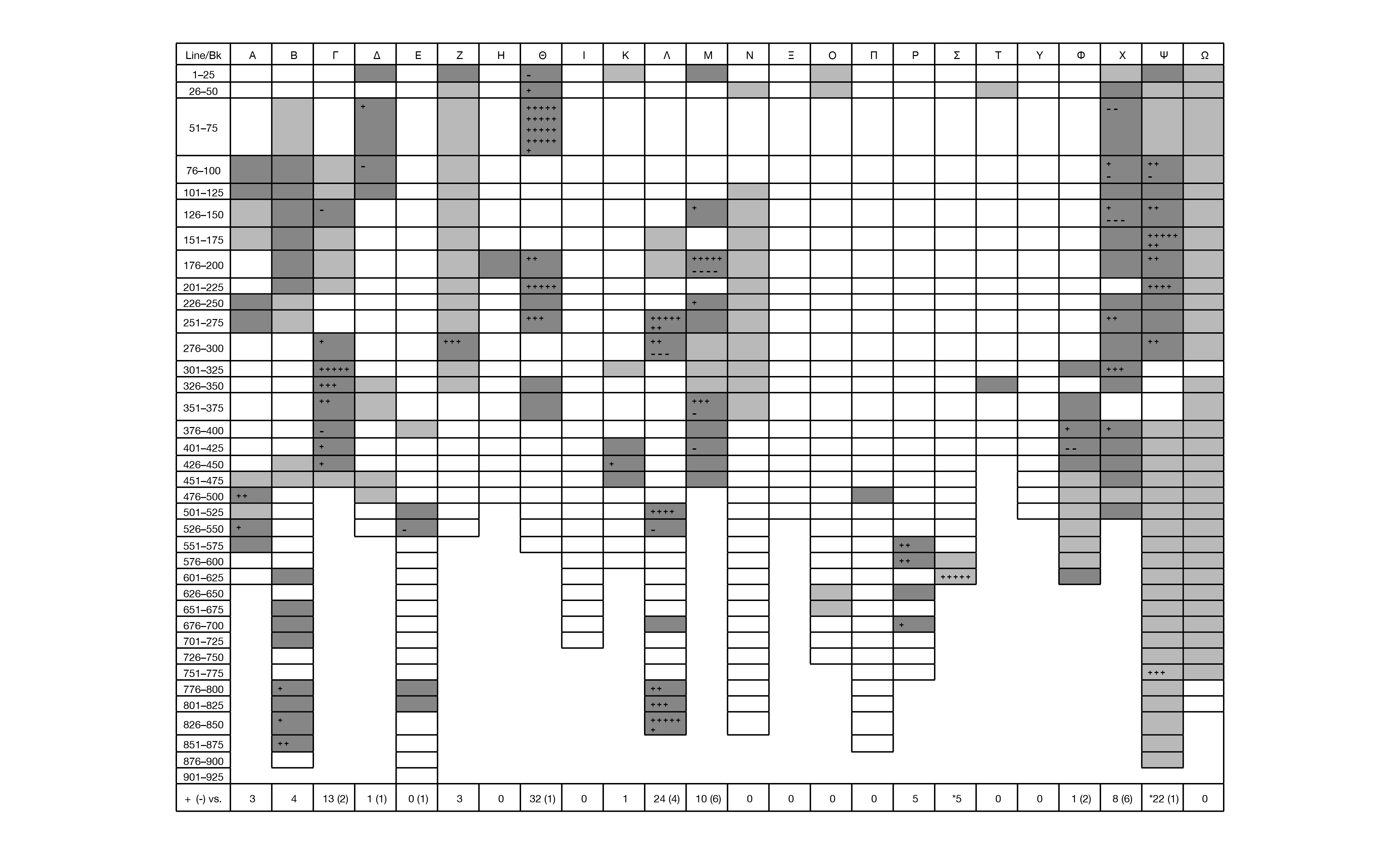

Next I give a complete list of "plus verses" and "minus verses" [68] for the Iliad as presented by the Ptolemaic papyri. [69] "Plus verses" are usually labeled following the last "known" line, starting with a, b, c, etc. "Plus verses" pre-ceding a known line are labeled with x, y, z. One immediately distinguishes those books having the largest numbers of "plus verses": III, VIII, XI, XII, and XXIII (and also those books with none), and an obvious question arises: were these books somehow more likely to "attract" "plus verses" (so West with reference to book VIII [70] )? But we also have to keep in mind the comments of Allen and Turner about the vagaries of chance. Maybe if we had more Ptolemaic papyri, the "plus verses" would be more evenly spread.

Ptolemaic "Plus Verses" by Book (Iliad)

| Book | No. +Verses | Location (=Line) | Papyrus | No. –Verses | Location (=Line) | Papyrus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | +3 | 484yz | P53 | 0 | ||

| 543a | P269 | |||||

| II | +4 | 794a, 855ab | P40 | 0 | ||

| 848a | w14 | |||||

| III | +13 | 283a, 302abcd, 304a, 339abc, 362a, 366a | P40 | -2 | 133, 389 | P391, P41 |

| 425a, 429a | h117 | |||||

| IV | +1 | 69a | P41 | -1 | 89a | P41 |

| V | 0 | -1 | 527 | P41 | ||

| VI | +3 | 280a, 288ab | P480a | 0 | ||

| VII | 0 | 0 | ||||

| VIII | +32? | 38a, 52abcd, 54abcd, 55abcd, 65abcd ... i, 197a, 199a, 202ab, 204a, 206a?b, 216a, 252ab, 255a | P7 | -1 | 6 | P593 |

| IX | 0 | 0 | ||||

| X | +1 | 433a | P609 | 0 | ||

| XI | +24 | 266abcd, 266yz, 272a, 280ab | P432 | -4 | 281-283c | P432 |

| 504a, 509a, 513a, 514a | P8 | 529 or 530d | ||||

| 795ab, 804a, 805a, 807a, 827abc, 834abe, 840a | P5 | |||||

| XII | +10f | 130a, 189bg, 190a, 193a | P432 | -6 | ||

| XII | 183a, 189ab, 190a, 250a, 360a, 363a, 370a | P217h | 184-187i, 369, 403 | P217 | ||

| XIII | 0 | 0 | ||||

| XIV | 0 | 0 | ||||

| XV | 0 | 0 | ||||

| XVI | 0 | 0 | ||||

| XVII | +5 | 574ab, 578ab | P501c | 0 | ||

| 683a | P672 | |||||

| XVIII | +5+j | 606a, 608abcd | P51k | 0 | ||

| XIX | 0 | 0 | ||||

| XX | 0 | |||||

| XXI | +1 | 382a | P12m | -2 | 402, 405 | P12 |

| XXII | +8 | 99a, 126a, 259ab, 316abc, 392a | P12 | -3/-6? | see noten | P12 |

| XXIII | +22 | 93a, 94a, 130a, 136a, 155a, 160a, 162a, 165a, 171a, 172ab, 183a, 195a, 209a, 221a, 223ab, 278ab | P12 | -1 | 92o | P12 |

| 757abc | P13p | |||||

| XXIV | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Totals | +132 | -21/-24 |

a Also omitted by Zenodotus.

b Either a “plus verse” or a different version of 207 (S. West 1967:89).

c XI 281–283 omitted by P432. S. West (1967:98) thinks that P432 may be “genuine” in omitting these lines.

d See S. West 1967:104, 107. There appears to be one line missing between 528 and 531.

e “There must have been at least two plus verses here” (S. West 1967:117).

f I count only once each the two “plus verses” 189b and 190a, which occur in both papyri.

g 189a is not preserved in P432, but is in P217.

h Formerly labeled as P121 and P342.

i S. West (1967:124) thinks the papyrus is “genuine” in omitting lines 184–187.

j “There must also have been some plus verses between 589 and 596” (West 1967:132). This papyrus contains critical signs next to some lines.

k P51 is dated after 150 BCE, but is still considered “Ptolemaic.”

m West 1967:137: “A second, rather cursive, hand has … inserted variants … [perhaps] a selection from various texts, a kind of primitive apparatus criticus.” Some marginal signs.

n Perhaps lines XXII 74–76 omitted. XXII 133–135 omitted, inserted after XXII 316.22.

o Line 92 was also athetized by Aristarchus. “This is the only place where an ancient athetesis corresponds to an omission in a pre-Aristarchean papyrus” (S. West 1967:171).

p P13 is dated after 150 BCE, but is still considered “Ptolemaic.”

b Either a “plus verse” or a different version of 207 (S. West 1967:89).

c XI 281–283 omitted by P432. S. West (1967:98) thinks that P432 may be “genuine” in omitting these lines.

d See S. West 1967:104, 107. There appears to be one line missing between 528 and 531.

e “There must have been at least two plus verses here” (S. West 1967:117).

f I count only once each the two “plus verses” 189b and 190a, which occur in both papyri.

g 189a is not preserved in P432, but is in P217.

h Formerly labeled as P121 and P342.

i S. West (1967:124) thinks the papyrus is “genuine” in omitting lines 184–187.

j “There must also have been some plus verses between 589 and 596” (West 1967:132). This papyrus contains critical signs next to some lines.

k P51 is dated after 150 BCE, but is still considered “Ptolemaic.”

m West 1967:137: “A second, rather cursive, hand has … inserted variants … [perhaps] a selection from various texts, a kind of primitive apparatus criticus.” Some marginal signs.

n Perhaps lines XXII 74–76 omitted. XXII 133–135 omitted, inserted after XXII 316.22.

o Line 92 was also athetized by Aristarchus. “This is the only place where an ancient athetesis corresponds to an omission in a pre-Aristarchean papyrus” (S. West 1967:171).

p P13 is dated after 150 BCE, but is still considered “Ptolemaic.”

The purpose of these tables is not to blind the reader with numerical data, but rather to attempt to show one of the most significant features of the Ptolemaic papyri—their "expansiveness" with regard to the "numerus versuum" [71] of the vulgate; these "plus verses," taken as a whole, amount to around three-quarters of a percent of the total lines of the "vulgate" text of the Iliad. In the next section I will systematically analyze a good number of these, showing, as many scholars have already recognized, that they can by no means be lumped together as careless or forgetful alterations to the standard text. I will in particular be looking at the surrounding contexts of many of the "plus verses," showing how, rather than being "inserted" arbitrarily into the text, they have rather "grown" into their current positions, resulting in an "organic"and—I argue—"authentic" alternative to our more familiar version. In other words, the two main types of textual variation, "vertical" and "horizontal," [72] tend to occur in concert much of the time, suggesting strongly that "plus verses" are part of a larger phenomenon, namely the tendency of oral transmission to both vary and expand (and occasionally contract) a portion of the Iliad in the midst of a performance.

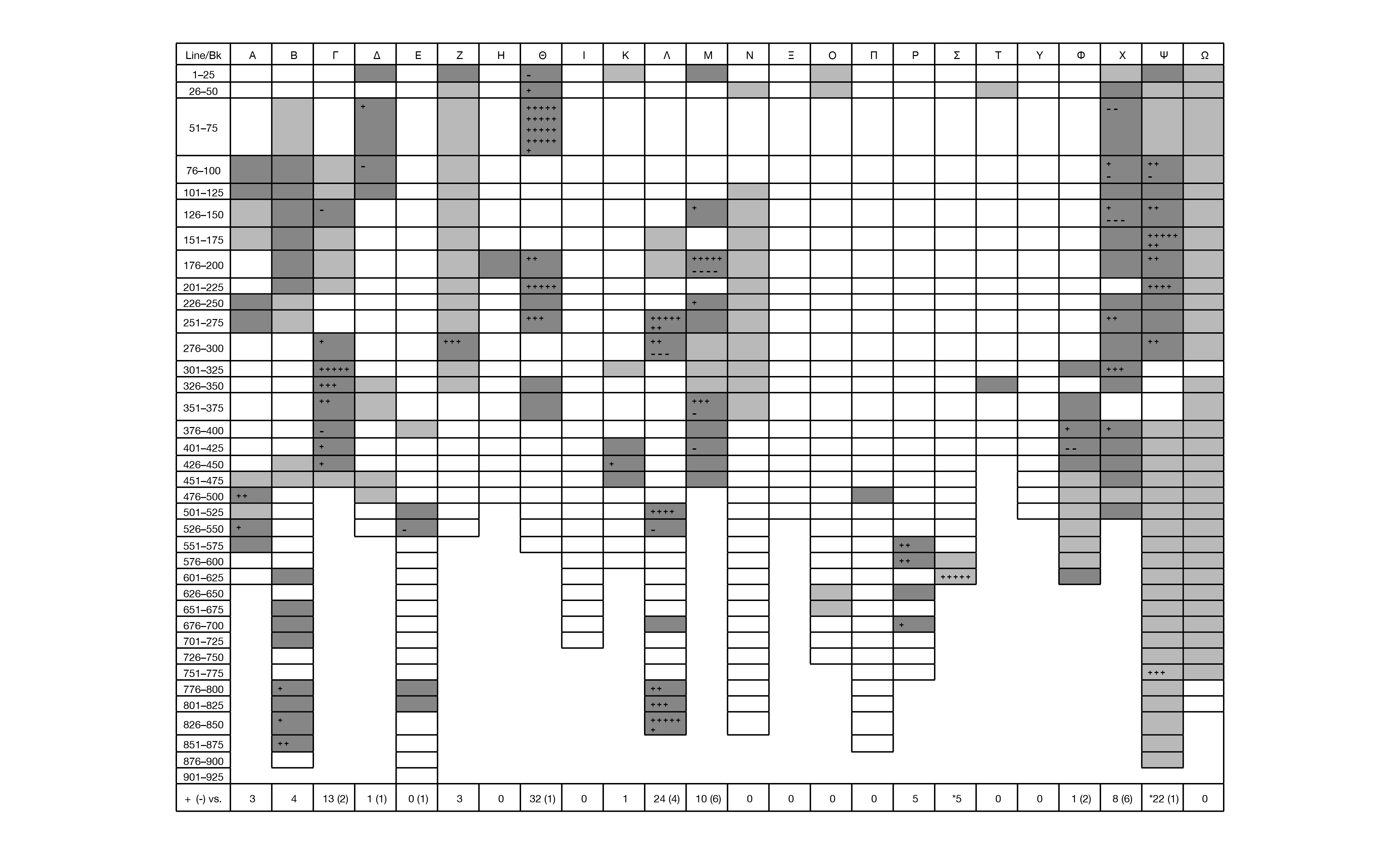

I conclude this section with one more graphic illustration of the distribution of the Ptolemaic "plus (and minus) verses" in the Iliad. On the following pages I show how the "plus and minus verses" are distributed throughout the Iliad. Each "cell" represents a 25-line block of text; [73] the darker shading represents parts of the Iliad covered—even if very fragmentarily—by one or more Ptolemaic papyri dating to before 150 BCE. The lighter shading represents passages covered by later Ptolemaic papyri—down to the end of the first century BCE. Within these blocks, "plus verses" are marked with a "+" and "minus verses" with a "–". What is significant from these charts is, first, how little of the Iliad is actually represented by papyri of the earlier or later Ptolemaic period—none of books IX, XIV, and XX, and very little of books XVI and XIX. Second, the "plus and minus verses" are almost exclusively confined to the earlier Ptolemaic period, specifically the time before the mid second century, the date when it is supposed that Aristarchus was compelled to leave the library at Alexandria. The charts further indicate, contrary to S. West's suggestion (above, n70), that the books containing relatively high proportions of "plus verses" are just those which happen to have a high degree of "coverage," rather than that they are somehow more likely to "attract" "plus verses" because of their content and style. The asterisks next to the totals for books XVIII and XXIII refer to the two papyri dating from after 150 BCE that contain "plus verses."

The charts should be read with their inherent limitations borne in mind: no indication is given of the condition of the individual papyri, nor of the fraction of each line preserved. In most cases lines do not survive in their entirety, but rather just their beginnings, ends, or middles; sometimes only one or two letters, and at times just an empty space indicating that there must have been one or more "plus verses." [74] Often there are fragments from the same original roll, with the intervening portion lost. But in spite of this, the main point I think holds: "plus verses"—at least the type found in the Ptolemaic papyri—are a uniquely early phenomenon, and reflect a distinctively different way in which the text of the Iliad was "behaving" at that time. I pursue this further now in the next section.

An Examination of Some Ptolemaic Papyrus Passages

In this section I look closely at a selection of passages from the Ptolemaic papyri, focusing primarily on "plus verses," but also examining the surrounding context of these unfamiliar lines, and looking at how, far from being simply "inserted" arbitrarily into Homeric episodes, these lines seem to fit "organically" into their locations.

My procedure will be first to give the immediate context of the passage in question, then to give the "vulgate" Greek text along with a fairly literal translation into English, and then provide the papyrus Greek text and translation. I then give an analysis of the papyrus text. I sometimes give more lines for context than there are in the papyrus, as papyri are so often torn at an inconvenient place in the text.

I follow several somewhat arbitrary but generally accepted conventions. I print both texts with lowercase script except for proper names; accents and breathing marks, including in reconstructed portions of text; iota adscript instead of subscript; and the two forms of lowercase sigma. Square brackets ([ ]) indicate where the papyrus has been torn away; a dot under a letter indicates that its reading is not certain. Sometimes there is an extended portion of a line where no letters can be made out; in such a case the space will be either blank or filled with dots, corresponding roughly to the number of "missing" letters. In these cases I also bracket the English translation, as an approximate way of showing how much (but rarely which actual Greek words) of a particular line is missing in the papyrus.

For the "vulgate" text I use Martin West's new Teubner edition of the Iliad, not to imply that he has slavishly followed the medieval manuscript tradition—indeed he frequently chooses "non-vulgate" readings, sometimes readings of one of the Alexandrians, sometimes scholarly conjectures, and sometimes a reading preserved by only a small number of witnesses. And as said previously in this book, his respect for the papyri—indicated by always citing their readings first—is much appreciated by those of us with an interest in papyri. I use West's text as the "standard" against which I compare the Ptolemaic papyrus readings. [75] This may seem like a contradiction to my stated aims, which include the principle that in cases where multiple variants exist, no one reading should automatically be privileged above all the others. However, I follow this procedure in the interests of practicality, and because, as people have generally viewed the texts of the Ptolemaic papyri as unusual or "wild" or "eccentric," I treat them, at least initially, as "marked" (in the linguistic sense of that term), meaning that there needs to be a corresponding "unmarked" or "default" text. My goal is to show, as has been acknowledged by S. West among others, that at one time these texts were no more unusual than any others of their time period. So my aim will be to demonstrate that the Ptolemaic papyrus readings are often as "good" or "authentic" as the "default" text.

I indicate where the papyrus reading differs from the Teubner by underlining all differences, including any "plus verses," and this both in the Greek and in the English. This allows the reader to see easily not only the "plus verses," but also how much other variation there is in the immediate context. Of course we cannot always be certain of the correctness of a particular reconstruction—it is quite possible that if we had more of a particular line of a papyrus surviving, it might differ substantially from our current conjecture, hence resulting in a papyrus even more "eccentric" than we had previously supposed.

Needless to say, my "defense" of some of these seemingly "eccentric" readings is not going to change the mind of anyone who has already decided in advance, as evidently had Bolling and van der Valk, that there could never be more than one "correct" reading in a given passage. But for those who have come to agree with Parry and Lord's understanding of oral poetry, its composition, performance, and transmission, the following analyses should seem hardly surprising or threatening; rather, I see them as a case of the evidence supporting the theory, and vice versa.

There are several questions that I have discussed previously, and which come to the fore now as we look at these passages of the Iliad. What does it mean to say that a line has been "interpolated"? We may have an idea of how and why it came to be in this specific location, but does that mean that it does not "belong" there now? How do the canons of textual criticism apply in these situations? For Bolling and others, the external evidence has nearly always seemed to be primary. But why should internal evidence be downplayed? And if the passage seems to read "better" without a given line and "worse" with it, should this, in the case of Homer, automatically mean that the line gets cut from the text? Don't performers perform "better" on some occasions than others, and while we may have a preference, is that the same as judging a reading to be "right" or "wrong"? For some these questions may have easy and decisive answers. But back to the text.

I follow Stephanie West's text for specific Ptolemaic papyri, except for those published subsequent to her 1967 book.1. Iliad III 302–312, as preserved in P40, with five "plus verses"; dated by S. West to between 285 and 250 BCE, but by M. West to the first half of the second century BCE. [76] Either way it is earlier than the 146/145 BCE date discussed in the previous chapter.

Immediate context: A duel has been agreed to between Menelaus and Paris. Agamemnon has just made a speech declaring the terms of the truce and duel, and has sacrificed lambs and poured wine on the ground. Interestingly, this is one of the few times when the death struggle of the sacrificial victims is described. [77] Soldiers on both sides are praying that anyone who breaks the conditions of the oaths may have their brains poured out on the ground and their wives controlled by (or sleep with) other men.First, the "vulgate" text:

302 ὣς ἔφαν· οὐδ' ἄρα πώ σφιν ἐπεκράαινε Κρονίων.

τοῖσι δὲ Δαρδανίδης Πρίαμος μετὰ μῦθον ἔειπεν·

"κέκλυτέ μοι, Τρῶες καὶ ἐϋκνήμιδες Ἀχαιοί.

305 ἤτοι ἐγὼν εἶμι προτὶ Ἴλιον ἠνεμόεσσαν

ἄψ, ἐπεὶ οὔ πω τλήσομ' ἐν ὀφθαλμοῖσιν ὁρᾶσθαι

μαρνάμενον φίλον υἱὸν ἀρηϊφίλωι Μενελάωι.

Ζεὺς μέν που τό γε οἶδε καὶ ἀθάνατοι θεοὶ ἄλλοι,

ὁπποτέρωι θανάτοιο τέλος πεπρωμένον ἐστίν."

310 ἦ ῥα, καὶ ἐς δίφρον ἄρνας θέτο ἰσόθεος φώς,

ἂν δ' ἄρ' ἔβαιν' αὐτός, κατὰ δ' ἡνία τεῖνεν ὀπίσσω·

πὰρ δέ οἱ Ἀντήνωρ περικαλλέα βήσετο δίφρον.

302 Thus they spoke, but the son of Kronos would not yet grant them fulfillment.

And Dardanian Priam spoke to them:

"Hear me, Trojans and well-greaved Achaeans;

305 Indeed I am going to windy Ilion

Again, since I will not dare to see with my own eyes

My own son fighting with Menelaus dear to Ares;

Zeus, no doubt, and the other immortal gods know

To which of the two the fate of death has been destined."

310 He spoke, and then the godlike man placed the lambs onto his chariot,

Then himself got on, and pulled the reins back;

And Antenor got onto the well-made chariot beside him.

Next, the Ptolemaic papyrus P40:

τοῖσι δὲ Δαρδανίδης Πρίαμος μετὰ μῦθον ἔειπεν·

"κέκλυτέ μοι, Τρῶες καὶ ἐϋκνήμιδες Ἀχαιοί.

305 ἤτοι ἐγὼν εἶμι προτὶ Ἴλιον ἠνεμόεσσαν

ἄψ, ἐπεὶ οὔ πω τλήσομ' ἐν ὀφθαλμοῖσιν ὁρᾶσθαι

μαρνάμενον φίλον υἱὸν ἀρηϊφίλωι Μενελάωι.

Ζεὺς μέν που τό γε οἶδε καὶ ἀθάνατοι θεοὶ ἄλλοι,

ὁπποτέρωι θανάτοιο τέλος πεπρωμένον ἐστίν."

310 ἦ ῥα, καὶ ἐς δίφρον ἄρνας θέτο ἰσόθεος φώς,

ἂν δ' ἄρ' ἔβαιν' αὐτός, κατὰ δ' ἡνία τεῖνεν ὀπίσσω·

πὰρ δέ οἱ Ἀντήνωρ περικαλλέα βήσετο δίφρον.

302 Thus they spoke, but the son of Kronos would not yet grant them fulfillment.

And Dardanian Priam spoke to them:

"Hear me, Trojans and well-greaved Achaeans;

305 Indeed I am going to windy Ilion

Again, since I will not dare to see with my own eyes

My own son fighting with Menelaus dear to Ares;

Zeus, no doubt, and the other immortal gods know

To which of the two the fate of death has been destined."

310 He spoke, and then the godlike man placed the lambs onto his chariot,

Then himself got on, and pulled the reins back;

And Antenor got onto the well-made chariot beside him.

302 [ὣς ἔφαν, εὐχό]μενοι, μέγα δ' ἔκτυπε μητίετα Ζεύ̣ς

302a [. . . . . . . . . . . .] φ̣ων ἐ̣π̣ὶ̣ δὲ στεροπὴν ἐφέηκεν·

302b [θησέμεναι γ]ὰρ̣ ἔμελλεν ἔτ᾽ ἄλγεά τε στοναχάς τε

302c [Τρωσί τε καὶ] Δαναο̣ῖ̣[σι] διὰ κρατερὰς ὑσ[μί]νας.

302d [αὐτὰρ ἐπεί ῥ᾽ ὄ]μοσέν τε τελεύτησέν [τε] τὸν ὅρκον,

303 [. . . . . . Δαρδανί]δ[η]ς̣ Πρίαμος πρὸς μῦθον ἔειπ[ε·

304 ["κέκλυτέ μοι Τ]ρῶες̣ καὶ Δάρδανοι ἠδ᾽ [ἐ]π̣ί̣κ̣[ουροι,

304 a[ὄφρ᾽ εἴπω] τά μ̣[ε θυ]μὸς ἐνὶ στήθεσσιν ἀν[ώ]γε[ι.

305 [ἤτοι ἐ]γὼν εἶμι πρ[ο]τὶ Ἴλιον ἠνεμόεσσαν·

306 [ο]ὐ̣ γάρ κεν τλαίην [ποτ᾽ ἐν ὀφθα]λμοῖσιν ὁρᾶ[σθαι

307 [μα]ρνάμ[ε]νον φίλο[ν υἱὸν ἀρηϊφίλωι Μενελάωι·

308 [Ζεὺς μέν που] τ̣ό̣ [γ]ε̣ [οἶδε καὶ ἀθάνατοι θεοὶ ἄλλοι,

309 [ὁπποτέρωι θα]ν̣ά̣τοιο τέλ[ος πεπρωμένον ἐστίν."

310 [ἦ ῥα, καὶ ἐς δίφρο]ν̣ ἄ̣ρ̣[νας θέτο ἰσόθεος φώς,

302 [Thus they spoke, pray]ing, and Zeus the counselor thundered greatly.

302a [ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .] and let loose a bolt of lightening:

302b [For he intended] to place further woes and groanings

302c [Upon the Trojans and] Danaans through fierce battles.

302d [But when he had] sworn and finished the oath,

303 [. . . . . . . Dardan]ian Priam spoke this word:

304 ["Hear me, T]rojans and Dardanian allies;

304a [While I say] what my heart in my breast is bidding me.

305 [Indeed] I am going to windy Ilion

For I would not [ever] dare to see with my own eyes

My own son fighting [with Menelaus dear to Ares;]

[Zeus] and [the other immortal gods know]

[To which of the two] the fate of dea[th has been destined."]

310 [He spoke, and then the godlike man placed] the la[mbs onto his chariot,]

302a [. . . . . . . . . . . .] φ̣ων ἐ̣π̣ὶ̣ δὲ στεροπὴν ἐφέηκεν·

302b [θησέμεναι γ]ὰρ̣ ἔμελλεν ἔτ᾽ ἄλγεά τε στοναχάς τε

302c [Τρωσί τε καὶ] Δαναο̣ῖ̣[σι] διὰ κρατερὰς ὑσ[μί]νας.

302d [αὐτὰρ ἐπεί ῥ᾽ ὄ]μοσέν τε τελεύτησέν [τε] τὸν ὅρκον,

303 [. . . . . . Δαρδανί]δ[η]ς̣ Πρίαμος πρὸς μῦθον ἔειπ[ε·

304 ["κέκλυτέ μοι Τ]ρῶες̣ καὶ Δάρδανοι ἠδ᾽ [ἐ]π̣ί̣κ̣[ουροι,

304 a[ὄφρ᾽ εἴπω] τά μ̣[ε θυ]μὸς ἐνὶ στήθεσσιν ἀν[ώ]γε[ι.

305 [ἤτοι ἐ]γὼν εἶμι πρ[ο]τὶ Ἴλιον ἠνεμόεσσαν·

306 [ο]ὐ̣ γάρ κεν τλαίην [ποτ᾽ ἐν ὀφθα]λμοῖσιν ὁρᾶ[σθαι

307 [μα]ρνάμ[ε]νον φίλο[ν υἱὸν ἀρηϊφίλωι Μενελάωι·

308 [Ζεὺς μέν που] τ̣ό̣ [γ]ε̣ [οἶδε καὶ ἀθάνατοι θεοὶ ἄλλοι,

309 [ὁπποτέρωι θα]ν̣ά̣τοιο τέλ[ος πεπρωμένον ἐστίν."

310 [ἦ ῥα, καὶ ἐς δίφρο]ν̣ ἄ̣ρ̣[νας θέτο ἰσόθεος φώς,

302 [Thus they spoke, pray]ing, and Zeus the counselor thundered greatly.

302a [ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .] and let loose a bolt of lightening:

302b [For he intended] to place further woes and groanings

302c [Upon the Trojans and] Danaans through fierce battles.

302d [But when he had] sworn and finished the oath,

303 [. . . . . . . Dardan]ian Priam spoke this word:

304 ["Hear me, T]rojans and Dardanian allies;

304a [While I say] what my heart in my breast is bidding me.

305 [Indeed] I am going to windy Ilion

For I would not [ever] dare to see with my own eyes

My own son fighting [with Menelaus dear to Ares;]

[Zeus] and [the other immortal gods know]

[To which of the two] the fate of dea[th has been destined."]

310 [He spoke, and then the godlike man placed] the la[mbs onto his chariot,]

The reconstruction of the beginning of line 302 ὣς ἔφαν εὐχόμενοι, 'thus they spoke, praying', occurs only in Iliad X 295 (although the singular participle occurs much more frequently): there Odysseus and Diomedes pray specifically to Athena, at some length, and she hears and in effect answers their prayers. Here the prayers are to Zeus, for any breaking of the oaths to be avenged. The "vulgate" has no mention of prayer, nor of Zeus thundering, just his reluctance to grant fulfillment to their wishes. In the papyrus, it appears that the poet continues with the idea of prayer; the verb κτυπέω is fairly rare, and generally seems to indicate trouble for one group, and maybe success for the other. But in Iliad XV 377, Zeus hears the prayer of Nestor, then ἔκτυπε 'crashed, thundered' to show he has heard his prayer; however he then gives help to the Trojans rather than the Greeks.

In the papyrus version, Zeus thunders and sends lightening (302a), but then (302b) 'was intending to place further woes and groanings upon [302c] both Trojans and Danaans ...'; so no one is about to be helped. S. West points out that thunder after a prayer in Homer "is normally a sign that it will be fulfilled." [78] She also, along with other scholars, finds lines 302b and c acceptable, but 302d "extremely suspect," because in all of its many other occurrences it always follows the actual swearing of an oath. [79] However the language of oaths has been used already (269, 279, 280), twice by Agamemnon, so I don't see the line as quite so objectionable. But this raises another question—if a line is used in an apparently "unique" way, does that prevent it from being "authentic"?

Line 302d has Priam as its subject; the Trojan preparation for the oaths has occurred in lines 245–258, so again it is not incongruous that Priam has finished his oath at this point. What is more interesting is the way in which the papyrus seems to emphasize Priam's fear of seeing his son Paris fight against Menelaus. In line 304 the papyrus has Priam talking only to Trojans and Trojan allies, as opposed to both Trojans and Greeks in the "vulgate." 304a adds a personal touch about Priam's internal unease, and in 306 the papyrus uses a potential optative rather than the future indicative, seeming to contribute to the emotional instability of Priam.

As in other passages to be considered, the papyrus gives the impression that it is a "version" of a performance with a somewhat heightened emotional tone. If this is so, what we have is apparently some sort of "transcript" of a particular performance. [80] 2. Iliad III 338–339c, again as preserved in P40, with three "plus verses."

Immediate context: Lots have just been cast by Hector, and Paris' lot has "jumped out" first, indicating that he should have the first spear throw in his duel with Menelaus. [81] Paris now begins to arm himself. I start at line 330 in the Teubner, although P40 really only starts this section at line 338 (the previous line has three letters surviving, and apparently was quite different from our line 337 [82] ).Teubner:

330 κνημῖδας μὲν πρῶτα περὶ κνήμηισιν ἔθηκεν

καλάς, ἀργυρέοισιν ἐπισφυρίοις ἀραρυίας·

δεύτερον αὖ θώρηκα περὶ στήθεσσιν ἔδυνεν

οἷο κασιγνήτοιο Λυκάονος, ἥρμοσε δ᾽ αὐτῶι·

ἀμφὶ δ᾽ ἄρ᾽ ὤμοισιν βάλετο ξίφος ἀργυρόηλον

335 χάλκεον· αὐτὰρ ἔπειτα σάκος μέγα τε στιβαρόν τε·

κρατὶ δ᾽ ἐπ᾽ ἰφθίμωι κυνέην εὔτυκτον ἔθηκεν

ἵππουριν· δεινὸν δὲ λόφος καθύπερθεν ἔνευεν·

εἵλετο δ᾽ ἄλκιμον ἔγχος, ὅ οἱ παλάμηφιν ἀρήρει.

ὣς δ᾽ αὔτως Μενέλαος ἀρήϊος ἔντε᾽ ἔδυνεν.

330 First he (i.e. Paris) put the greaves around his legs,

fine ones, fitted with silver ankle-pieces.

Second he put on his breastplate about his chest,

of his brother Lycaon; and fitted it to himself.

And about his shoulders he threw his silver-studded sword

335 of bronze, and then his shield great and sturdy.

And upon his mighty head he put a well-made helmet

with horse-hair crest; and terribly did the plume nod from above.

And he took a stout spear, which fitted his hands.

And likewise warlike Menelaus donned his battle gear.

P40:

338 εἵλε̣[το δ᾽ ἄλκιμα] δοῦρε δύ̣[ω κεκορυθμένα χαλκῶι.

339 ὣς δ᾽ αὔ̣[τως Μεν]έλαος ἀρήϊα [τεύχε᾽ ἔδυνεν,

339 aἀσπίδα κ[αὶ πήλη]κα φαεινὴ[ν καὶ δύο δοῦρε

339 bκαὶ καλὰ[ς κνη]μῖδας ἐπισφ[υρίοις ἀραρυίας,

339 cἀμφὶ δ᾽ ἄ[ρ᾽ ὤμοισι]ν βάλετο ξί[φος ἀργυρόηλον

338 And he took two [stout] spears, [tipped with bronze.

339 And like[wise Men]elaus donned his [warlike armor,

339a His shield a[nd shin]ing helmet, [and two spears

339b And fine greaves fitted [with ankle-pieces,

339c And about his [shoulders] he threw his si[lver-studded sword.

Conceivably two different readers could come up with opposite conclusions about this passage. One might say that the added lines are repetitive—we have already had the arming of Paris, so lines dealing with that of Menelaus are redundant. Conversely, another could want Menelaus to be given more than just one line, as if Paris were stealing the limelight. Of course we are fully expecting Paris to lose this duel, so giving him the longer arming scene enhances the ominous nature of the passage.καλάς, ἀργυρέοισιν ἐπισφυρίοις ἀραρυίας·

δεύτερον αὖ θώρηκα περὶ στήθεσσιν ἔδυνεν

οἷο κασιγνήτοιο Λυκάονος, ἥρμοσε δ᾽ αὐτῶι·

ἀμφὶ δ᾽ ἄρ᾽ ὤμοισιν βάλετο ξίφος ἀργυρόηλον

335 χάλκεον· αὐτὰρ ἔπειτα σάκος μέγα τε στιβαρόν τε·

κρατὶ δ᾽ ἐπ᾽ ἰφθίμωι κυνέην εὔτυκτον ἔθηκεν

ἵππουριν· δεινὸν δὲ λόφος καθύπερθεν ἔνευεν·

εἵλετο δ᾽ ἄλκιμον ἔγχος, ὅ οἱ παλάμηφιν ἀρήρει.

ὣς δ᾽ αὔτως Μενέλαος ἀρήϊος ἔντε᾽ ἔδυνεν.

330 First he (i.e. Paris) put the greaves around his legs,

fine ones, fitted with silver ankle-pieces.

Second he put on his breastplate about his chest,

of his brother Lycaon; and fitted it to himself.

And about his shoulders he threw his silver-studded sword

335 of bronze, and then his shield great and sturdy.

And upon his mighty head he put a well-made helmet

with horse-hair crest; and terribly did the plume nod from above.

And he took a stout spear, which fitted his hands.

And likewise warlike Menelaus donned his battle gear.

P40:

338 εἵλε̣[το δ᾽ ἄλκιμα] δοῦρε δύ̣[ω κεκορυθμένα χαλκῶι.

339 ὣς δ᾽ αὔ̣[τως Μεν]έλαος ἀρήϊα [τεύχε᾽ ἔδυνεν,

339 aἀσπίδα κ[αὶ πήλη]κα φαεινὴ[ν καὶ δύο δοῦρε

339 bκαὶ καλὰ[ς κνη]μῖδας ἐπισφ[υρίοις ἀραρυίας,

339 cἀμφὶ δ᾽ ἄ[ρ᾽ ὤμοισι]ν βάλετο ξί[φος ἀργυρόηλον

338 And he took two [stout] spears, [tipped with bronze.

339 And like[wise Men]elaus donned his [warlike armor,

339a His shield a[nd shin]ing helmet, [and two spears

339b And fine greaves fitted [with ankle-pieces,

339c And about his [shoulders] he threw his si[lver-studded sword.

S. West discusses the papyrus variant lines in the light of "all the great arming scenes in Homer." [83] She lists the following: Iliad V 735ff. (Athena), XI 16ff. (Agamemnon), XIX 364ff. (Achilles), and Odyssey xxii 122ff. (Odysseus); she further states that the order is always the same: 1) greaves, 2) cuirass (or breastplate), 3) sword, 4) shield, 5) helmet, and 6) spear (or spears). She makes the comment that it was particularly important to put on the shield before the helmet, for reasons of convenience: the plume of the helmet would interfere with the shield-strap if the helmet were donned before the shield. [84]

In considering the papyrus' "additional lines" 339abc, I observe firstly that the shield does still precede the helmet: indeed, items 4, 5, and 6 appear in order at the beginning, with greaves and sword being placed last. Now the preceding lines (328–338) have all dealt with the arming of Paris (using several lines repeated in other arming scenes), with that of Menelaus getting only the single line 339 in the "vulgate." The papyrus version gives Menelaus four lines instead of one, and moreover none of the three extra lines is repeated from the earlier description, indeed one is "unique" in Homer. Rather than Menelaus' arming being simply a repetition of that of Paris, it is more of a summary, with shield, helmet, and spears all mentioned in the same line. Thus one scholar's claim that the papyrus version "has brought down the Homeric passage to the level of primitive epic poetry" by unartistic and tedious repetition, which "only says that the armor of Menelaus was identical with that of Paris," [85] is simply false, and overlooks the obvious: the second description relates to the first by not repeating it, which would perhaps be rather "tedious" (to use the same scholar's term), but rather by summarizing it, as mentioned above. In fact, the additional line 339a uses words for shield and helmet which are different from those used in Paris' arming. Thus the papyrus version still focuses upon Paris' arming, but also devotes some space to that of Menelaus: the two go together without any problems of "tedious" or "artless" repetition. (I note that, in contrast to van der Valk, Kirk suggests that a fuller description of Menelaus' arming would have underlined the unbalanced nature of the contest. [86] This seems to me as unlikely, if not more so, than van der Valk's suggestions.) In this connection I note other "abbreviated" scenes which mention lists of arms, such as Iliad XIII 264–265 (which is admittedly not an actual arming scene), where spears and shields appear in one line, helmets and breastplates in the other. [87]

Zenodotus, according to the scholia to Venetus A, had the lines in an order similar to those of P40, and Rengakos notes that Zenodotus' text has a striking parallel in the Argonautica of Apollonius of Rhodes, with the arming of Aietes before his fight with Jason: the order of weapons corresponds identically, to the point that neither arming-scene includes mention of a sword. [88] This is a case in which the reading of Zenodotus can be shown to have a basis in an existing version of the text, rather than being a "subjective conjecture."

Thinking of the two versions from a performance perspective, one can imagine a singer on a particular occasion getting a heightened sense of the drama of the upcoming duel—it is clear after all that Paris is the weaker fighter; he has been allotted first strike, meaning he is going be the loser, so to speak; and so our particular singer gives Paris two spears, as well as making not Menelaus but his armor "warlike"; and then giving Menelaus four lines instead of one for his arming. These are variations that would seem perfectly natural as a way of performing this particular episode at a higher emotional level than on some other occasion.

Lines 339b and c occur elsewhere in Homer; line 339a does not, although its formulas πήληκα φαεινὴν and δύο δοῦρε occur elsewhere in Homer, the latter frequently in the same part of the line. [89] What does this prove? We know that the ancient Alexandrians seemed to have an aversion for repeated lines, an aversion shared by several modern scholars. In fact in the medieval manuscript Venetus A the "asterisk" sign was placed next to lines that Aristarchus noted occurred in other locations; if in addition the "obelos" sign was placed next to the asterisk, then in Aristarchus' judgment the line in question "belonged" in the other location, but not in the one in question. [90] This may have been understandable for the Alexandrians—but is it necessarily the right approach for us? Just because a line occurs elsewhere, even fairly closely to its current location, is this an indication that one of the occurrences must be "wrong"? Iliad VI 269 and 279 are identical and only ten lines apart, but as far as I know no edition omits one or other line.3. Iliad VI 280–292, as preserved in P480a, [91] with three "plus verses"; dated "Ptolemaic."

Immediate context: Hecuba has just tried to persuade her son Hector to rest, drink some wine, and pour a libation to Zeus and the other gods. Hector declines, saying that the wine will weaken him, and that in his current state, covered with blood and gore, he is in no condition to offer libations to the gods. He gives her instructions in order to try and appease the wrath of Athena by taking her a richly woven robe.Teubner:

"ἀλλὰ σὺ μὲν πρὸς νηὸν Ἀθηναίης ἀγελείης

280 ἔρχε᾽, ἐγὼ δὲ Πάριν μετελεύσομαι, ὄφρα καλέσσω,

αἴ κ᾽ ἐθέλησ᾽ εἰπόντος ἀκουέμεν. ὥς κέ οἱ αὖθι

γαῖα χάνοι· μέγα γάρ μιν Ὀλύμπιος ἔτρεφε πῆμα

Τρωσί τε καὶ Πριάμωι μεγαλήτορι τοῖό τε παισίν.

εἰ κεῖνόν γε ἴδοιμι κατελθόντ᾽ Ἄϊδος εἴσω,

285 φαίην κεν φίλον ἦτορ ὀϊζύος ἐκλελαθέσθαι."

ὣς ἔφαθ᾽· ἣ δὲ μολοῦσα ποτὶ μέγαρ᾽ ἀμφιπόλοισιν

κέκλετο, ταὶ δ᾽ ἄρ᾽ ἀόλλισσαν κατὰ ἄστυ γεραιάς.

αὐτὴ δ᾽ ἐς θάλαμον κατεβήσετο κηώεντα,

ἔνθ' ἔσάν οἱ πέπλοι παμποίκιλοι, ἔργα γυναικῶν

290 Σιδονιῶν, τὰς αὐτὸς Ἀλέξανδρος θεοειδής

ἤγαγε Σιδονίηθεν ἐπιπλοὺς εὐρέα πόντον

τὴν ὁδόν, ἣν Ἑλένην περ ἀνήγαγεν εὐπατέρειαν.

"But you, go to the shrine of Athena who carries the spoil,

280 and I will go and look for Paris, to call him,

if perhaps he wishes to hear what I have to say. I wish for him the earth

would gape right now; for the Olympian reared him as

a great source of pain for the Trojans and for great-hearted Priam and his children.

If I were to see him having gone down into Hades,

285 I would say that my own heart had forgotten its grief."

Thus he spoke; and she went to the hall and called

to her maids, and they gathered together the older women throughout the city.

But she went down to the sweet-smelling chamber,

Where her many-colored robes were, the work of Sidonian

290 Women, whom godlike Alexander himself

Had led from Sidon when he sailed the wide sea,

That journey on which he brought back Helen of the noble father.

P480a:

280 ἔρχε᾽, ἐγὼ δὲ Πάριν μετελεύσομαι, ὄφρα καλέσσω,

αἴ κ᾽ ἐθέλησ᾽ εἰπόντος ἀκουέμεν. ὥς κέ οἱ αὖθι

γαῖα χάνοι· μέγα γάρ μιν Ὀλύμπιος ἔτρεφε πῆμα

Τρωσί τε καὶ Πριάμωι μεγαλήτορι τοῖό τε παισίν.

εἰ κεῖνόν γε ἴδοιμι κατελθόντ᾽ Ἄϊδος εἴσω,

285 φαίην κεν φίλον ἦτορ ὀϊζύος ἐκλελαθέσθαι."

ὣς ἔφαθ᾽· ἣ δὲ μολοῦσα ποτὶ μέγαρ᾽ ἀμφιπόλοισιν

κέκλετο, ταὶ δ᾽ ἄρ᾽ ἀόλλισσαν κατὰ ἄστυ γεραιάς.

αὐτὴ δ᾽ ἐς θάλαμον κατεβήσετο κηώεντα,

ἔνθ' ἔσάν οἱ πέπλοι παμποίκιλοι, ἔργα γυναικῶν

290 Σιδονιῶν, τὰς αὐτὸς Ἀλέξανδρος θεοειδής

ἤγαγε Σιδονίηθεν ἐπιπλοὺς εὐρέα πόντον

τὴν ὁδόν, ἣν Ἑλένην περ ἀνήγαγεν εὐπατέρειαν.

"But you, go to the shrine of Athena who carries the spoil,

280 and I will go and look for Paris, to call him,

if perhaps he wishes to hear what I have to say. I wish for him the earth

would gape right now; for the Olympian reared him as

a great source of pain for the Trojans and for great-hearted Priam and his children.

If I were to see him having gone down into Hades,

285 I would say that my own heart had forgotten its grief."

Thus he spoke; and she went to the hall and called

to her maids, and they gathered together the older women throughout the city.

But she went down to the sweet-smelling chamber,

Where her many-colored robes were, the work of Sidonian

290 Women, whom godlike Alexander himself

Had led from Sidon when he sailed the wide sea,

That journey on which he brought back Helen of the noble father.

280 "ἔρχευ, ἐγὼ] δὲ Πάριν μετελ[εύ]σομαι, ὄφρα καλέσσ[ω,

280a ] ον στονόεντα μ[. . . . .]ρ̣ω̣α̣ . . α . τ . . ω . ο̣υ̣

]ι εἰπόντος ἀκουέμεν· ὥ̣ς̣ κ̣έ̣ οἱ αὖθι

γαῖα χάν]οι· μέγα γάρ μιν Ὀλύμπιος ἔτραφε πῆμα

Τρωσί τε] καὶ Πριάμω μεγαλήτορι τοῖό τε παισίν·

εἰ κεῖνόν] γε ἴδοιμι κατελθόντ᾽ Ἄϊδος εἴ̣σ̣ω,

285 φαίην κε] φρέν᾽ ἀτέρπου ὀϊζύος ἐκλελαθέσθαι."

ὣς ἔφατ᾽, ο]ὐδ᾽ ἀπίθησ᾽ Ἑκάβη, ταχὺ δ᾽ ἀ[μ]φιπόλοισι

κέκλετο· ταὶ δ᾽ ἄ]ρ᾽ ἀόλλισσαγ κατὰ ἄστ[υ] γε̣ραιάς·

288 αὐτὴ δ᾽ ἐς] θάλαμογ κατεβήσετο κηωίεντα,

288a κέδρινον] ὑψερεφῆ ὃς γλήνη πολλ᾽ ἐκεκεύθει

288b ] φωριαμοῖσι παρί[στ]ατο δῖα γυνα[ικῶν

ἔνθ᾽ ἔσάν οἱ ]πέπλοι παμπο[ίκι]λοι ἔργα γυν[αικῶν

290 Σιδονίων, τὰς α]ὐτὸς Ἀλέξανδ[ρος θεοειδὴς

ἤγαγε Σιδονίη]θεν, ἐπιπλ[ὼς εὐρέα πόντον,

τὴν ὁδὸν ἣν Ἑλέ]νη[ν περ ἀνήγαγεν εὐπατέρειαν·

280 "You go, and I will go and look for Paris, to call him,

280a . . . . . carrier of woe? . . . . .

if perhaps he wishes] to hear what I have to say. I wish for him the earth

would gape right] now; for the Olympian reared him as a great source of pain

for the Trojans] and for great-hearted Priam and his children.

If I were to see] him having gone down into Hades,

285 I would say] that my own mind had forgotten its painful grief."

Thus he spoke,] nor did Hecuba disobey, but quickly called

to her maids,] and they gathered together the older women throughout the city.

But she went] down to the sweet-smelling chamber,

288a Made of cedar] which contained many noble treasures

288b ] queenly among women, she stood beside the chests

Where her] many-colored robes were, the work of Sidonian

290 Women, whom] godlike Alexand[er himself

Had led from Sidon] when he sail[ed the wide sea,

That journey on which he brought back He]le[n of the noble father.

Beginning this time with the first "plus verse," 282a, we see that it is poorly preserved, with the only complete word able to be made out being στονόεντα 'groaning, bringing or causing groans'. Elsewhere in Homer this word is used four times with βέλεα or βέλεμνα 'weapons' and once with κήδεα 'woes'. In this passage it conceivably could be referring to Paris, which would tie in with the following sentiment of Hector, that he wishes Paris might be swallowed up by the earth and go down to Hades. This would be not only a unique usage, but also a powerful way of comparing Paris to a spear that brings grief to others, in particular his own family members. And the usage fits in well here with the following words πῆμα 'bane, destruction', and ὀϊζύς 'sorrow, grief'. Similarly, line 285 in the papyrus has the uncommon adjective ἀτέρπου 'causing pain' used to describe Hector's sorrow; in contrast, the "vulgate" gives the adjective φίλον, which means little more here than 'my own' as referring to Hector's heart. The papyrus version is attributing to Hector a stronger sense of grief and sorrow than is our more familiar text. Once again we might imagine a performer feeling Hector's "pain" to an unusual degree, and using diction with a greater degree of emotional intensity.280a ] ον στονόεντα μ[. . . . .]ρ̣ω̣α̣ . . α . τ . . ω . ο̣υ̣

]ι εἰπόντος ἀκουέμεν· ὥ̣ς̣ κ̣έ̣ οἱ αὖθι

γαῖα χάν]οι· μέγα γάρ μιν Ὀλύμπιος ἔτραφε πῆμα

Τρωσί τε] καὶ Πριάμω μεγαλήτορι τοῖό τε παισίν·

εἰ κεῖνόν] γε ἴδοιμι κατελθόντ᾽ Ἄϊδος εἴ̣σ̣ω,

285 φαίην κε] φρέν᾽ ἀτέρπου ὀϊζύος ἐκλελαθέσθαι."

ὣς ἔφατ᾽, ο]ὐδ᾽ ἀπίθησ᾽ Ἑκάβη, ταχὺ δ᾽ ἀ[μ]φιπόλοισι

κέκλετο· ταὶ δ᾽ ἄ]ρ᾽ ἀόλλισσαγ κατὰ ἄστ[υ] γε̣ραιάς·

288 αὐτὴ δ᾽ ἐς] θάλαμογ κατεβήσετο κηωίεντα,

288a κέδρινον] ὑψερεφῆ ὃς γλήνη πολλ᾽ ἐκεκεύθει

288b ] φωριαμοῖσι παρί[στ]ατο δῖα γυνα[ικῶν

ἔνθ᾽ ἔσάν οἱ ]πέπλοι παμπο[ίκι]λοι ἔργα γυν[αικῶν

290 Σιδονίων, τὰς α]ὐτὸς Ἀλέξανδ[ρος θεοειδὴς

ἤγαγε Σιδονίη]θεν, ἐπιπλ[ὼς εὐρέα πόντον,

τὴν ὁδὸν ἣν Ἑλέ]νη[ν περ ἀνήγαγεν εὐπατέρειαν·

280 "You go, and I will go and look for Paris, to call him,

280a . . . . . carrier of woe? . . . . .

if perhaps he wishes] to hear what I have to say. I wish for him the earth

would gape right] now; for the Olympian reared him as a great source of pain

for the Trojans] and for great-hearted Priam and his children.

If I were to see] him having gone down into Hades,

285 I would say] that my own mind had forgotten its painful grief."

Thus he spoke,] nor did Hecuba disobey, but quickly called

to her maids,] and they gathered together the older women throughout the city.

But she went] down to the sweet-smelling chamber,

288a Made of cedar] which contained many noble treasures

288b ] queenly among women, she stood beside the chests

Where her] many-colored robes were, the work of Sidonian

290 Women, whom] godlike Alexand[er himself

Had led from Sidon] when he sail[ed the wide sea,

That journey on which he brought back He]le[n of the noble father.

In line 286, Hecuba, rather than just μολοῦσα 'going', rather does not disobey, and quickly calls her maidservants, intensifying the more mundane "vulgate" version. The formulaic phrase οὐδ᾽ ἀπίθησ᾽ occurs about twenty-five times in Homer, generally of Hera, Iris, Thetis, and Zeus, but also of humans such as Achilles and Agamemnon. The only other human female it is used of is Eurycleia in Odyssey xxii 492, after being ordered by Odysseus to assist with cleaning the hall after the deaths of the suitors. For a listener familiar with that story this has to add to the power of the phrase being used in this present context. One is also reminded of Telemachus and Penelope, but even then Penelope is not spoken of as 'not disobeying' her son.

In the two following lines, 287 and 288, we notice two seemingly minor textual variants (I pass over κηωίεντα for now): ἀόλλισσαγ κατὰ and θάλαμογ κατεβήσετο. These are clear examples of spelling reflecting pronunciation (in these two cases assimilation of a nasal to the following velar stop), in a way that presumably would not happen if the lines were being dictated slowly and carefully. Rather I suggest that these spellings convey the memory of a live performance, with all its speed and dramatic intensity.

Lines 288a and b are the remaining "plus verses." 288a recalls Iliad XXIV 192, where Priam is getting jewels and other precious materials in order to ransom the body of Hector, and telling Hecuba what he is planning to do. Priam also asks Hecuba what she thinks of his plan. The hearer of this slightly "longer" papyrus version will feel the poignancy of the connection between the two visits to the treasure chamber, the former by Hecuba at the command of Hector in order to appease the wrath of Athena, the second by Priam, to the dismay of Hecuba, in order to ransom the body of that same Hector. [92]

Line 288b and the following lines recall Odyssey xv 104, where Helen is taking the finest robe from her treasure chests as a gift for Telemachus. She too is called there δῖα γυναικῶν; and there is the added connection that Hecuba's robes came from the same journey that Paris was on when he brought back Helen to Troy. It is as if the poet, aware that he will soon be telling of the finest robe that Hecuba must give to Athena, the one that ἀστὴρ δ᾽ ὣς ἀπέλαμπεν 'shone like a star' and ἔκειτο δὲ νείατος ἄλλων 'lay underneath all the rest' (Iliad VI 295), makes a link to the robe of Helen with those same words (Odyssey xv 108), and hence Hecuba becomes like Helen for a brief moment. But what pains Helen brought to Hecuba! And those pains are being brought into the present context by means of the allusion to Priam in Iliad book XXIV.

To conclude: the poet has used more words and more intense words to express the grief of Hector; this has led to a more decisive reaction by Hecuba, which has then helped to make a connection with both Priam, Helen, Paris, and Hector himself. I repeat one of my earlier points: these "plus verses" are an inherent part of the story—of this particular version of the story, that in some ways has more emotional "power" than the version to which we are more accustomed. To write them off as "concordance interpolations"—lines merely inserted into a passage because of some connection from elsewhere—and hence needing to be "excised," means that we miss out on some significant intertextual relationships, and hence on some of the many linking references within the poem and between the Iliad and Odyssey.4. Iliad XVII 566–584, as preserved in P501c, with four "plus verses"; dated "Ptolemaic." [93]

Immediate context: The Greeks are fighting over the body of Patroclus. Menelaus has just prayed to Athena to help protect him from Trojan weapons, and from Hector in particular.Teubner:

"χαλκῶι δηϊόων· τῶι γὰρ Ζεὺς κῦδος ὀπάζει."

ὣς φάτο· γήθησεν δὲ θεὰ γλαυκῶπις Ἀθήνη,