-

Gregory Nagy, Masterpieces of Metonymy: From Ancient Greek Times to Now

Acknowledgments

List of Extracts

Introduction

I: Making metonyms both naturally and artistically

II: Interweaving metonymy and metaphor

III: Masterpieces of metonymy on the Acropolis

IV: The metonymy of a perfect festive moment

Epilogue without end: A metonymic reading of a love story

Bibliography

Part Four: The metonymy of a perfect festive moment

4§01. In Part Three, we saw how the Parthenon Frieze tells the myth of a prototypical Panathenaic Procession. And we also saw how this myth, like the ritual of the recurrent Panathenaic Procession that it aetiologizes, follows the logic of a metonymic sequence. Here in Part Four, we will see in general that the culmination of such a sequence—the most decisive step in a series of consecutive steps—is a perfect festive moment. It is a moment of feeling delight in experiencing the beauty and the pleasure of attending a festival. In the ancient Greek passages that I am about to analyze, the relevant word for ‘feeling delight’ is terpesthai.

4§02. At first sight, there is a problem with the formulation I just offered. The English expression feeling delight seems at first too subjective for describing something that someone actually experiences at a festival: does the Greek word terpesthai, translated as ‘feeling delight’, really say anything objective about an ancient Greek festival?

4§03. In confronting this problem, I will concentrate on one particular aspect of festivals, which is, the singing and the dancing as described in Homeric poetry and beyond. In the course of reading these poetic descriptions, we will have ample opportunity to reconsider our first impressions about the idea of ‘feeling delight’ at a festival. What we will find is that the wording that expresses this idea is in fact not subjective but programmatic.

4§04. The word that I translate as ‘feeling delight’, terpesthai, is present in every one of the first eleven passages that I have selected to analyze here in Part Four: Extracts 4-A, 4-B, 4-C, 4-D, 4-E, 4-F, 4-G, 4-H, 4-I, 4-J, 4-Κ. The last of these eleven passages, Extract 4-K, will reveal the most decisive contextual evidence, and, by the time we reach this passage, we will have seen clearly the programmatic function of the word terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ in referring to festive moments of singing and dancing. At the end of each one of the eleven Extracts, I will add a special note drawing attention to the presence of this word terpesthai. {173|174}

Introducing the most festive of all moments in the Iliad

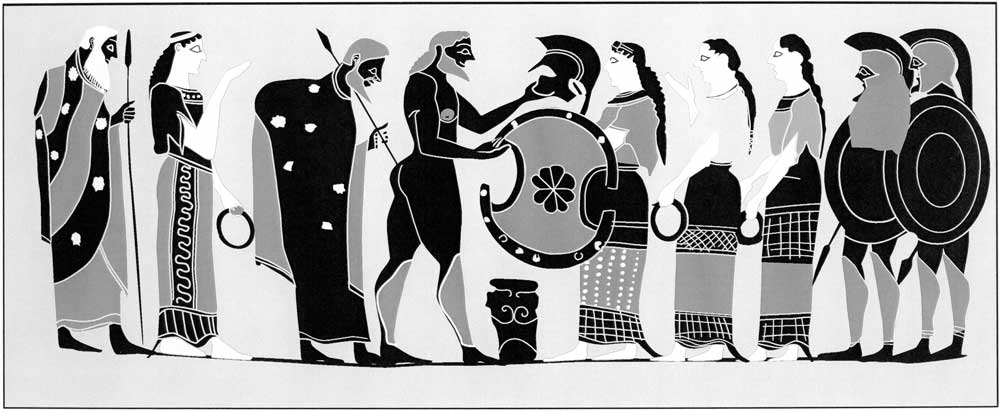

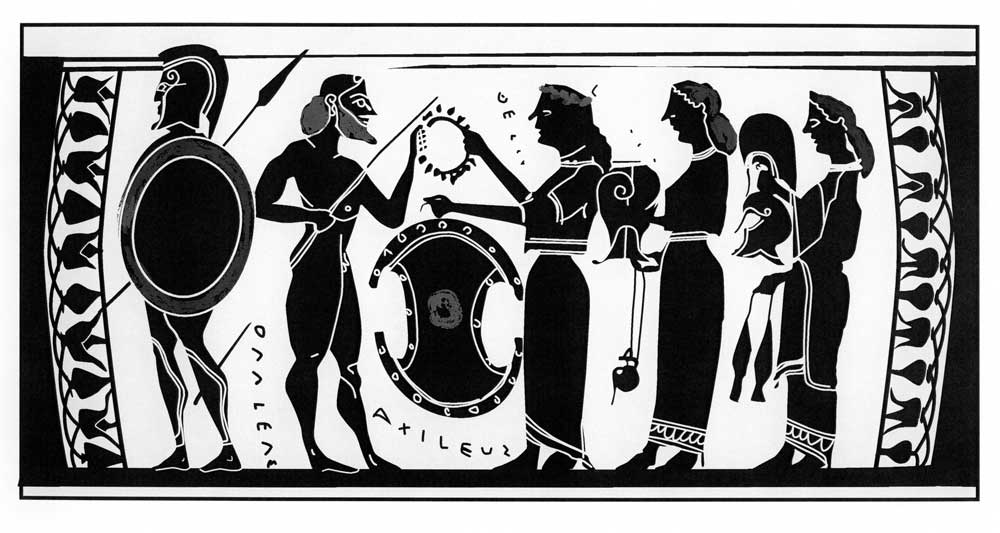

4§1. The setting for my first example of festive moments signaled by the word terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ is a passage describing a picture created by the divine artisan Hephaistos in the process of his metalworking the Shield of Achilles in Iliad XVIII. The picture is metalworked into the bronze surface of the shield. The text that describes this picture, which I will quote presently in Extract 4-A, is relevant to the ten texts that will follow it in Extracts 4-B, 4-C, 4-D, 4-E, 4-F, 4-G, 4-H, 4-I, 4-J, 4-K.

4§2. In this picture, we will see a festive moment of singing and dancing, and the key word describing the reaction of all those attending is terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ at line 604 of Iliad XVIII here. Before we can view the text and the context, however, I need to give some background about the Homeric Shield of Achilles as a work of art in its own right.

Pattern-weaving as a metaphor for metalworking

4§3. In Part Three, we saw how the visual art of weaving the Peplos of Athena was a model for the various forms of visual art that adorned the Parthenon. Relevant here is one special detail, which is the fact that the sacred charter myth about a cosmic battle between the Giants and the Olympians was not only pattern-woven into the Peplos but also metalworked into the concave interior surface of the gigantic bronze shield that was positioned next to the commensurately gigantic gold-and-ivory statue of the goddess. As we will now see, this convergence of visual narration as pattern-woven into a fabric and as metalworked into bronze is re-enacted in the picture that I am about to analyze.

4§4. This picture, metalworked into the surface of the Shield of Achilles in Iliad XVIII, is a Homeric masterpiece of ekphrasis. I have in mind here the most basic sense of this technical term ekphrasis, which is, an imitation of visual art by verbal art. In this case, the verbal art of poetry performs a narration that was supposedly performed by the visual art of metalwork in bronze. And the poetry visualizes the performer of this narration as none other than the god of metalwork himself, the divine smith Hephaistos, whose primary medium of metalwork is bronze, as we know from the Homeric description of the god as a khalkeus ‘bronzeworker’ (Iliad XV 309).

4§5. The performance of metalwork by Hephaistos, as we will see, is expressed by way of a powerful metaphor: in the extract that I am about to quote from Iliad XVIII, the god’s act of metalworking his narration into bronze is compared to an act of pattern-weaving that same narration into fabric, as if {174|175} the divine metalworker were pattern-weaving a peplos. And the word here for pattern-weave is poikillein, which occurs in the very first line of my quoted extract:

Extract 4-A

|590 The renowned one [= Hephaistos], the one with the two strong arms, pattern-wove [poikillein] [1] into it [= the Shield of Achilles] a place for singing-and-dancing [khoros]. [2] |591 It [= the khoros] was just like the one that, once upon a time in far-ruling Knossos, |592 Daedalus made for Ariadne, the one with the beautiful tresses [plokamoi]. |593 There were young men there, [3] and young women who are courted with gifts of cattle, |594 and they all were dancing [orkheîsthai] with each other, holding hands at the wrist. |595 The girls were wearing delicate dresses, while the boys were clothed in tunics [khit ōn plural] |596 well woven, gleaming exquisitely, with a touch of olive oil. |597 The girls had beautiful garlands [stephanai], while the boys had knives |598 made of gold, hanging from knife-belts made of silver. |599 Half the time they moved fast in a circle, with expert steps, |600 showing the greatest ease, as when a wheel, solidly built, is given a spin by the hands |601 of a seated potter, who is testing it whether it will run well. |602 The other half of the time they moved fast in straight lines, alongside each other. |603 A huge crowd stood around the place of the song-and-dance [khoros] that rouses desire, |604 and they were feeling delight [terpesthai]; [4] in their midst sang-and-danced [melpesthai] a divine singer [aoidos], |605 playing on the special lyre [phorminx]; [5] two special dancers [kubistētēre] among them |606 were swirling as he led [ex-arkhein] [6] the singing-and-dancing [molpē] in their midst.

Iliad XVIII 590–606 [7] {175|176}

Special note: as in the other ten passages in the sequence of Extracts 4-A through 4-K, I highlight here the context of terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ at line 604.

4§6. In contemplating this picture, the mind’s eye sees the metalwork executed by the god Hephaistos, that ultimate bronzeworker: as I have already noted, that is what Hephaistos is actually called by Homeric poetry, a khalkeus ‘bronzeworker’ (Iliad XV 309). Metaphorically, however, the actual epic narration of the Shield in the Iliad is figured not only as metalwork, specifically as bronzework, but also as pattern-weaving: we have just seen the decisive word, poikillein, in the first line of the extract I just quoted (XVIII 590).

Back to pattern-weaving as a metaphor for Homeric poetry

4§7. The craft of pattern-weaving is especially privileged as a metaphor for the craft of metalworking, since it is also a metaphor for the craft of making Homeric poetry, as we saw in Part Two when we considered the Iliadic passages picturing the web that was pattern-woven by Andromache, quoted in Extract 2-O, and the web that was pattern-woven by Helen, quoted in Extract 2-P. Virgil understood this privileging of the metaphor of pattern-weaving: in the Aeneid, the metalwork of the divine smith Vulcan in producing the Shield of Aeneas is described there as an act of weaving a ‘web’, a textus (Aeneid 8.625). [8]

4§8. So, the ekphrasis of the Shield of Achilles in Iliad XVIII is one step removed from a metaphor for Homeric poetry, since the metaphor that compares the metalworking of this Shield to the pattern-weaving of a web can be seen as an ingenious substitution for the metaphor that compares the making of Homeric poetry itself to this same privileged process of pattern-weaving. {176|177}

Pattern-weaving Homer himself into his own web

4§9. Having just considered again the centrality of pattern-weaving as a metaphor for the verbal art of Homeric poetry, this time in the context of lines 590–606 in Iliad XVIII, quoted in Extract 4-A, I now take a closer look at lines 603–606 in that same extract. We find in these four lines something we see nowhere else in texts of the Iliad as they have survived into our time. Right in the center of the festive scene that is pattern-woven into the metaphorical web of pictures created by Homeric poetry is a singer who is none other than Homer himself.

4§10. Perhaps this Homer is not the kind of Homer we may have expected to find, but here he is, for all to see. That is what I will now argue.

Homer as a lead singer

4§11. In arguing that the singer we see in lines 603–606 of Iliad XVIII is meant to be Homer himself, I start by focusing on the fact that this singer is shown here in the act of taking the lead in the performance of a khoros. This word khoros means ‘chorus’ in the sense of a singing-and-dancing group. [9] I quickly add here in passing that I have started to use hyphens in saying singing-and-dancing, but I will postpone till a later point my rationale for using such a format.

4§12. To reword my argument in terms of this meaning of khoros ‘chorus’ as a singing-and-dancing group, I am saying that Homer in the present context is imagined as a lead singer who participates in the singing-and-dancing of such a choral group. In making this argument, I will highlight five words that we find in lines 603–606 of Iliad XVIII. I start by quoting again these four lines:

Extract 4-B (four lines re-quoted from 4-A)

|603 A huge crowd stood around the place of the song-and-dance [khoros] that rouses desire, |604 and they were feeling delight [terpesthai]; in their midst sang-and-danced [melpesthai] a divine singer [aoidos], |605 playing on the special lyre [phorminx]; [10] two special dancers [kubistētēre] among them |606 were swirling as he led [ex-arkhein] [11] the singing-and-dancing [molpē] in their midst.

Iliad XVIII 603–606 [12] {177|178}

Special note: as in the other ten passages in the sequence of Extracts 4-A through 4-K, I highlight here the context of terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ at line 604.

4§13. I have already indicated, in the special note immediately above, the first of the five words that especially concern me in Extract 4-B here, which is terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ at line 604. But I am not yet ready to explain my reasons for highlighting this word.

4§14. So, without any further explanation for now, I proceed to the second of the five words that I highlight here, which is the noun khoros ‘chorus’ at line 603. In general, as I have already observed with reference to an earlier occurrence of khoros, at line 590 as quoted in Extract 4-A, this word can refer not only to a choral group of singers-and-dancers but also to the place where the singing-and-dancing happens, and the relationship of the place to the group inside that place is a fine example of synecdoche: the place for the grouping is seen as the grouping itself. And, to return to my translation of line 603, the word khoros in this context can refer not only to a singing-and-dancing group but also to the place where the group is performing.

4§15. The third and the fourth words that I highlight here in lines 603–606 of Iliad XVIII are the verb melpesthai at line 604 and the noun molpē at line 606: both of these words, as we know from other contexts, refer to the combined activities of singing and dancing in a khoros or choral group. [13] Because these words melpesthai and molpē combine the idea of singing with the idea of dancing, I will consistently translate them in a hyphenated format, ‘singing-and-dancing’. In fact, I have been using this format from the start in defining the word khoros as a ‘singing-and-dancing group’, in order to highlight the fact that this Greek word khoros, unlike the borrowed English word chorus, includes dance.

4§16. The fifth and last word that I highlight in this passage is the verb ex-arkhein at line 606, which signals an individuated act of performance that interacts with the collective performance of a khoros as a singing-and-dancing group. [14]

4§17. I now offer an overall interpretation of Iliad XVIII 603–606, as just quoted in Extract 4-B, in which these five words occur. I focus on the picturing of an individuated singer who is singing while playing on a phorminx, which is a special kind of lyre. He is flanked by two individuated dancers, kubistētēre. The three of them are surrounded by a choral group of radiant young men and women who are not only dancing but also evidently singing, as we see from the contexts of the words khoros at line 603 and melpesthai/molpē at lines 604/606. {178|179} The lead singer himself is not only singing but also dancing—or at least he is participating in the overall choral dancing, as we see again from the contexts of the words melpesthai/molpē at lines 604 /606. So, this lead singer too is part of the overall khoros. And all of them—the lead singer together with the choral group—are performing to the delight of a huge crowd. Here I come back to the programmatic word terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ at line 604.

4§18. I said a while ago that Homer, as pattern-woven into the metaphorical web created by Homeric poetry, is here for all to see. But now I must add a major qualification. The fact is, Homer is “here” only in one version of the Homeric textual tradition. We will now consider an alternative version—and this version is the one that actually survives in the medieval manuscripts—where we see no Homer at all. I now show the text of this alternative version:

Extract 4-C (three lines different in meaning from the four lines quoted in 4-B)

|603 A huge crowd stood around the place of the song-and-dance [khoros] that rouses desire, |604 and they were feeling delight [terpesthai]; in their midst sang-and-danced [melpesthai] a divine singer [aoidos], |605 playing on the special lyre [phorminx]; [15] two special dancers [kubistētēre] among them |606 were swirling as they led [ex-arkhein] [16] the singing-and-dancing [molpē] in their midst.

Iliad XVIII 603–606 [17]

Special note: as in the other ten passages in the sequence of Extracts 4-A through 4-K, I highlight here the context of terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ at line 604.

4§19. A part of the wording here—the part that I indicate with a double strikethrough—is not attested in the medieval manuscript tradition: ‘|604 and they were feeling delight [terpesthai]; in their midst sang-and-danced [melpesthai] a divine singer [aoidos], |605 playing on the special lyre [phorminx]; two special dancers [kubistētēre] among them |606 …’. [18] This missing part in Iliad XVIII 603–606 {179|180} was restored by Friedrich August Wolf in his 1804 edition of the Iliad, and the relevant line-numbering 604–605 in current editions of the Iliad reflects that restoration, going back to the edition of Wolf. [19] The restoration, as I call it, is based on what we read in a source that dates back to the late second century CE, Athenaeus (his relevant text can be found at 5.180c–e, 181a–f). [20] From this source, we learn about the treatment of Iliad XVIII 603–606 in the Homeric text edited by Aristarchus, whose editorial work can be dated to the middle of the second century BCE. As we learn from Athenaeus (5.181c), Aristarchus rejected as un-Homeric the part of the wording that I have translated this way: ‘|604 … in their midst sang-and-danced [melpesthai] a divine singer [aoidos], |605 playing on the special lyre [phorminx] … |606 …’. [21] But, as we also learn from Athenaeus (again 5.181c), Aristarchus did not reject the same wording in another Homeric context, at Odyssey iv 17–18, where we read once again: ‘|17 … in their midst sang-and-danced [melpesthai] a divine singer [aoidos], |18 playing on the special lyre [phorminx] … |19 …’. [22] And, in fact, this wording is preserved for Odyssey iv 17–18 in the medieval manuscript tradition.

4§20. I quote here the full context of the passage I just cited from the Odyssey:

Extract 4-D

|15 So they feasted throughout the big palace with its high ceilings, |16 both the neighbors and the kinsmen of glorious Menelaos, |17 and they were feeling delight [terpesthai]; in their midst sang-and-danced [melpesthai] a divine singer [aoidos], |18 playing on the special lyre [phorminx]; two special dancers [kubistētēre] among them |19 were swirling as he led [ex-arkhein] [23] the singing-and-dancing [molpē] in their midst.

Odyssey iv 15–19 [24]

Special note: as in the other ten passages in the sequence of Extracts 4-A through 4-K, I highlight here the context of terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ at line 17. {180|181}

4§21. I just quoted the reading ‘as he led’ (ex-arkhontos), indicated by Athenaeus (5.180d, 5.181d) both for this line, at Odyssey iv 19, and for the line at Iliad XVIII 606. [25] With regard to this reading, Athenaeus (5.180d) also indicates that the editor Aristarchus and his followers had accepted an alternative reading ‘as they led’ (ex-arkhontes) at Odyssey iv 19—as also in Iliad XVIII 606. [26] In fact, it is this alternative reading (ex-arkhontes) that we find preserved in the medieval manuscripts of both the Iliad and the Odyssey. Still, as the wording of Athenaeus indicates further, his own preferred reading ‘as he led’ (ex-arkhontos) existed in ancient times as a textual variant that had been noted by Aristarchus—even though that editor preferred the alternative textual variant ‘as they led’ (ex-arkhontes).

4§22. I focus here on the methodology of Aristarchus in making these judgments. Here was a scholar whom the ancient world generally acclaimed as the greatest of all experts in the editing of the Homeric texts. His working procedure was to track variations in the Homeric textual tradition by collating manuscripts that were available to him—and then to publish in his hupomnēmata or ‘commentaries’ his scholarly judgments in choosing which textual variants were authentically Homeric and which ones were supposedly not. [27] In the case of line 606 in Iliad XVIII, I argue, we are dealing with two textual variants that were known to Aristarchus, ‘as he led’ (ex-arkhontos) and ‘as they led’ (ex-arkhontes); in his commentaries, he evidently expressed his judgment that the second of these variants was authentically Homeric while the first was supposedly un-Homeric. [28]

4§23. Then, about 350 years later, Athenaeus seized an opportunity to show off his own learning by criticizing this particular judgment of Aristarchus about the two textual variants, arguing that the authentically Homeric version is really the first one, ‘as he led’ (ex-arkhontos) and not the second one, ‘as they led’ (ex-arkhontes).

4§24. In the larger context of the passage where line 606 occurs, that is, in lines 603–606 of Iliad XVIII, Aristarchus had evidently found a related textual variation, in the form of a longer four-line version as quoted in Extract 4-B and a shorter three-line version as quoted in Extract 4-C. In the case of these lines 603–606 of Iliad XVIII, Aristarchus judged the shorter three-line textual variant of this passage to be the authentically Homeric one. And the three-line variant requires the reading ‘as they led’ (ex-arkhontes), since there exists in this version no singular referent to which the alternative reading ‘as he led’ (ex-arkhontos) {181|182} could refer. Only in the case of the four-line variant could there be room for allowing either the reading ‘as they led’ (ex-arkhontes), with the plural referent, or the reading ‘as he led’ (ex-arkhontos), with the singular referent. In this case, it all depends on whether the leading of the chorus is ascribed respectively to the one singer or to the two dancers.

4§25. And, here again, Aristarchus is criticized for his judgment by Athenaeus, who argues on the basis of comparable contexts that only a singer can lead off a choral performance, not dancers. In terms of this criticism, only the longer four-line version could be authentic, and, even in this case, such a longer version would require the reading ‘as he led’ (ex-arkhontos), which refers to the singer, since the reading ‘as they led’ (ex-arkhontes) would be simply wrong.

4§26. In terms of my argument, however, the authenticity of the longer version does not rule out the possibility that the shorter version is also authentic. As we will see, both versions can be authenticated. And what really matters, I argue, is that Aristarchus in the course of his collating Homeric manuscripts could verify here the existence of both a longer and a shorter textual variant, and that he makes note of the variation itself in his commentaries. [29] What Athenaeus is criticizing here is simply the judgment of Aristarchus in preferring one textual variant instead of another. But the fact is, if Aristarchus had not mentioned two variants in this case, Athenaeus would have had nothing to criticize.

4§27. More important for now, both of the textual variants at line 606 of Iliad XVIII, ‘as he led’ (ex-arkhontos) and ‘as they led’ (ex-arkhontes), can be shown to be formulaic variants as well. [30] To say it more forcefully, the existence of these forms as textual variants was determined by their pre-existence as formulaic variants.

4§28. Here is what I mean. The form and the meaning of both variants can be explained in terms of variations that existed in the formulaic system of the Homeric language, which stemmed from an oral poetic tradition and thus did not depend on the technology of writing for either the composition or the performance of Homeric poetry. Just as any language is a system, so also the special language of Homeric poetry was a system, albeit a specialized one, and therefore this special language has to be analyzed as a system in its own right. The basic formal components of this system are known as formulas, and that is why I describe Homeric poetry in terms of a formulaic system. In using these terms formulas and formulaic system, I follow the lead of Milman Parry and {182|183} Albert Lord, who perfected a methodology for analyzing the textual tradition of Homeric poetry in terms of the formulaic system underlying the textualization of this poetry. [31]

4§29. So, applying the approach of Parry and Lord, I am arguing that the variants ‘as he led’ (ex-arkhontos) and ‘as they led’ (ex-arkhontes), attested in Odyssey iv 19 and in Iliad XVIII 606, are independent of the Homeric textual tradition and depend instead on pre-existing variations that derive from the formulaic system of Homeric poetry. [32]

4§30. These two variants, I will now go on to argue, stem from two different narrative scenarios corresponding to the longer and the shorter versions of the wording transmitted for lines 603–606 of Iliad XVIII. According to the shorter version as signaled by ‘as they led’ (ex-arkhontes) at line 606, which is the reading I quote in Extract 4-C, it is the two individuated dancers whose performance leads into the choral singing-and-dancing. According to the longer version as signaled by ‘as he led’ (ex-arkhontos), which is the reading I quote in Extract 4-B, the individuated singer combines his performance with the corresponding performance of two individuated dancers who flank him as he leads into the choral singing-and-dancing.

4§31. These two scenarios both resemble, in different ways, what happens in Odyssey viii when Demodokos the blind singer performs the second of his three songs:

Extract 4-E

|250 [Alkinoos is speaking.] “Let’s get started. I want the best of the Phaeacian acrobatic dancers [bētarmones] |251 to perform their sportive dance [paizein], [33] so that the stranger, our guest, will be able to tell his near-and-dear ones, |252 when he gets home, how much better we (Phaeacians) are than anyone else |253 in sailing and in footwork, in dance [orkhēstus] and song [aoidē]. |254 One of you go and get for Demodokos the clear-sounding special lyre [phorminx], |255 bringing it to him. It is in the palace somewhere.” |256 Thus spoke Alkinoos, the one who looks like the gods, and the herald [kērux] got up, |257 ready {183|184} to bring the well carved phorminx from the palace of the king. |258 And the organizers [aisumnētai], the nine selectmen, all got up |259 —they belonged to the district [dēmos]—and they started arranging everything according to the rules of the competition [agōn]: |260 they made smooth the place of the singing-and-dancing [khoros], and they made a wide space of competition [agōn]. |261 The herald [kērux] came near, bringing the clear-sounding phorminx |262 for Demodokos. He [= Demodokos] moved to the center [es meson] of the space. At his right and at his left were boys [kouroi] |263 in the first stage of adolescence [prōthēboi], standing there, well versed in dancing [orkhēthmos]. |264 They pounded out with their feet a dance [khoros], a thing of wonder, and Odysseus |265 was observing the sparkling footwork. He was amazed in his heart [thūmos]. |266 And he [= Demodokos], playing on the phorminx [phormizein], started [anaballesthai] singing beautifully |267 about [amphi] the bonding [philotēs] of Ares and of Aphrodite, the one with the beautiful garlands [stephanoi], |268 about how they, at the very beginning, [34] mated with each other in the palace of Hephaistos, |269 in secret. [The story that has just started at line 266 now continues, ending at line 366.] |367 These things, then, the singer [aoidos] was singing [aeidein], that very famous singer. As for Odysseus, |368 he felt delight [terpesthai] in his heart as he was listening—and so too did all the others feel, |369 the Phaeacians, those men with their long oars, men famed for their ships.

Odyssey viii 250–269, 367–369 [35]

Special note: as in the other ten passages in the sequence of Extracts 4-A through 4-K, I highlight here the context of terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ at line 368. {184|185}

4§32. I paraphrase what we have just seen narrated here, in the larger context of Odyssey viii 248–380. [36] To start, a special lyre called the phorminx is brought to Demodokos (lines 254, 257), and then he proceeds es meson ‘to the center’ (262) of the space where the performance is to take place; that space is a khoros ‘chorus’ (260)—and we have already seen that this word can refer both to a singing-and-dancing group and to the place where the group performs. This space has been smoothed over (260), and it is enveloped by a wider overall space that is marked out for accommodating a vast assembly of people attending what is described here as a competitive event. The one word that is used in this context to express two meanings, both ‘assembly of people’ and ‘competitive event’, is agōn (259 and 260). Participating in this competitive event of choral performance are the young men of the Phaeacians, who are described as specially skilled performers at such events (248–253); among the words that we see in this description are khoroi ‘choruses’ (248), orkhēstus ‘dancing’ (253), and aoidē ‘singing’ (253). Also participating in this competitive event is the singer in the center, Demodokos himself. When this singer makes his way es meson ‘to the center’ (again, 262) of the space set aside for the performance, he is surrounded by kouroi ‘boys’ (262) whose nimble feet are already pounding out the rhythm of the song on the surface of the space set aside for singing-and-dancing. And the word for this space here again is khoros (264). Meanwhile the singer starts ‘singing’, aeidein (266), while accompanying himself on the special lyre called the phorminx (266). His song, about the love affair of Ares and Aphrodite, is now retold, and the retelling takes one hundred lines exactly within the framing narrative of the Odyssey: he starts at 266 and ends at 366. So, what is the reaction of the disguised Odysseus, who is the primary character attending this performance of Demodokos? The answer is, as we see in the text as I quoted it here in Extract 4-E, Odysseus terpeto ‘felt delight’ (368), and the same delighted reaction was experienced, it is said, by everyone else attending the performance (368–369). Then the virtuoso song of this individuated singer Demodokos leads into a virtuoso performance by two individuated dancers (370–379). Responding to these dancers in choral performance are the rest of the kouroi ‘boys’ (379–380).

4§33. So, in the formulaic wording that I have just paraphrased from Odyssey viii, we find a wealth of free-standing comparative evidence that I can cite in support of authenticating both the longer and the shorter versions of lines 603–606 in Iliad XVIII, as quoted respectively in Extract 4-B and Extract 4-C. These two different versions, I argue, would have suited two different eras in the evolution of Homeric poetry as a formulaic system. In an earlier era, Homer would have been appreciated as a lead singer who could interact with choral {185|186} singing-and-dancing; in a later era, by contrast, he would be a solo singer, and so he could no longer fit into a festive scene of choral performance.

4§34. For the moment, I highlight one detail that stands out in the longer and older version of lines 603–606 in Iliad XVIII as quoted in Extract 4-B: there is an individuated lead singer here, flanked by two individuated dancers, and this picture matches closely what we see in Odyssey viii 370–379, which likewise shows an individuated lead singer flanked by two individuated dancers. Conversely, the focus on the two individuated dancers instead of the one individuated singer in this part of the description in Odyssey viii 370–379 is comparable to what we see in the shorter and newer version of lines 603–606 in Iliad XVIII, quoted in Extract 4-C, where the figure of the lead singer is occluded—and thus excluded from any possibility of interacting with the choral performance that is being described.

4§35. Pursuing further my argument that the Iliad, like the Odyssey, shows a lead singer whose performance interacts with choral singing-and-dancing, I now come to a new piece of evidence. We see it in Odyssey xiii, where the singer Demodokos performs one last song before Odysseus leaves the land of the Phaeacians. The occasion is most festive, marking the conclusion of the overall festivities that had started in Odyssey viii—and had continued ever since then. Bringing these festivities to a spectacular close, Alkinoos the king of the Phaeacians slaughters a sacrificial ox to the god Zeus, and this animal sacrifice is the cue for Demodokos to emerge once again as the lead singer in the midst of a festive crowd:

Extract 4-F

|24 On their [= the Phaeacians’] behalf Alkinoos, the one with the holy power, sacrificed an ox |25 to Zeus, the one who brings dark clouds, the son of Kronos, and he rules over all. |26 Then, after burning the thigh-pieces, they feasted, feasting most gloriously, |27 and they were feeling delight [terpesthai]; in their midst sang-and-danced [melpesthai] the divine singer [aoidos], |28 Demodokos, honored by the people.

Odyssey xiii 24–28 [37]

Special note: as in the other ten passages in the sequence of Extracts 4-A through 4-K, I highlight here the context of terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ at line 27. {186|187}

4§36. We see here in line 27 of Odyssey xiii exactly the same wording that we saw in line 17 of Odyssey iv, quoted in Extract 4-D. More important, we see the same wording also in line 604 of Iliad XVIII, quoted in Extract 4-B and already in Extract 4-A, that is, in the line that shows a part of the longer version of Iliad XVIII 603–606 as restored by Wolf. In each one of these three lines that I just listed, Odyssey xiii 27 and iv 17 and Iliad XVIII 604, a solo singer is shown, but the individuated soloist is leading into a choral song combined with dance, as signaled by the word melpesthai in all three contexts. This word, as we have seen, combines the idea of singing with the idea of dancing—that is, choral dancing. That is why I have translated melpesthai all along in a hyphenated format, ‘singing-and-dancing’.

4§37. The passage I have just quoted in Extract 4-F from Odyssey xiii 24–28 is a most decisive piece of comparative evidence validating the authenticity of the corresponding passage in the longer version of Iliad XVIII 603–606, quoted earlier in Extract 4-B and even earlier in Extract 4-A. Both of these two passages show an individuated lead singer in the midst of a festive crowd surrounding a choral performance that brings delight to all. Both in Odyssey xiii 27 and in Iliad XVIII 604, the decisive word that shows the interaction of the individuated lead singer with choral performance is melpesthai ‘sing-and-dance’. [38] But the passage in Odyssey xiii 24–28 occludes any direct mention of dancers, thus differing from the corresponding passage in the longer version of Iliad XVIII 603–606, which highlights two individuated dancers as well as a chorus. Conversely, the passage in the shorter version of Iliad XVIII 603–606, quoted earlier in Extract 4-C, occludes any direct mention of a singer, thus differing from the corresponding passage in Odyssey xiii 24–28, quoted just now in Extract 4-F, which highlights Demodokos as an individuated lead singer.

4§38. The decisive evidence of this passage in Odyssey xiii 24–28 is missing from the reportage of Athenaeus (5.181c) about the editorial decisions of Aristarchus concerning Odyssey iv 15–19 and Iliad XVIII 603–606. And it is missing also from the argumentations of those who build theories about various kinds of textual interpolation; according to one such theory, for example, the longer version of Iliad XVIII 604–605 results from some kind of “rhapsodic intervention,” which supposedly happened at some undetermined stage in the history {187|188} the Homeric textual tradition. [39] The problem with this kind of theorizing is that it fails to account for the formulaic nature of such an “intervention.” [40] As we have seen by now, the evidence of the wording in Iliad XVIII 604–605 indicates that both the shorter and the longer versions result from formulaic variation. [41]

Homer as the lead singer of the Homeric Hymn to Apollo

4§39. So far, I have highlighted three Homeric passages, two of them in the Odyssey and one in the Iliad, where we see a lead singer interacting with the performance of a choral group. Now we turn to the Homeric Hymn (3) to Apollo, where we are about to see once again a lead singer in the act of interacting with a choral performance. And, in this case, we have evidence from the historical period that the lead singer was actually recognized as Homer himself, as we learn from the explicit testimony of the historian Thucydides:

Extract 4-G

|3.104.2 … After the ritual purification [of the sacred island of Delos], the Athenians at that point for the first time turned the festival known as the Delia into a quadrennial [instead of an annual] festival. |3.104.3 Even in the remote past, there had been at Delos a great [annual] coming together of Ionians and neighboring islanders [nēsiōtai], and they were celebrating [ἐθεώρουν ‘were making theōriā’] along with their wives and children, just as the Ionians in our own times come together [= at Ephesus] for [the festival of] the Ephesia. A competition [agōn] was held there [= in Delos], both in athletics and in mousikē (tekhnē), [42] and the cities brought choruses [khoroi]. |3.104.4 Homer makes it most clear that such was the case in the following verses [epos plural], which come from a prooimion [43] of Apollo: {188|189}

[[beginning of quotation by Thucydides]] |146 But when, O Phoebus [Apollo], in Delos more than anywhere else you feel delight [terpesthai] in your heart [thūmos], |147 there the Ionians, with tunics [khitōn plural] trailing, gather |148 with their children and their wives, along the causeway [aguia], [44] |149 and there with boxing [pugmakhiē] and dancing [orkhēstus] and song [aoidē] |150 they have you in mind and make you feel delight [terpein], whenever they set up a competition [agōn]. [[end of quotation by Thucydides, who now resumes his own comments]]

|3.104.5 That there was also a competition [agōn] in mousikē (tekhnē), [45] in which the Ionians went to engage-in-competition [agōnizesthai], again is made clear by him [= Homer] in the following verses, taken from the same prooimion. [46] After making the subject of his hymn [humnos] the Delian chorus [khoros] of women, he was drawing toward the completion [telos] of his song of praise, drawing toward these verses [epos plural], in which he also makes mention of himself—

[[beginning of further quotation by Thucydides]] |165 But come now, may Apollo be gracious, along with Artemis; |166 and you all also, hail [khairete] and take pleasure, all of you [Maidens of Delos]. Keep me, even in the future, |167 in your mind, whenever someone, out of the whole mass of earthbound humanity, |168 comes here [to Delos], after arduous wandering, someone else, and asks this question: |169 “O Maidens, who is for you the most pleasurable of singers |170 that wanders here? In whom do you take the most delight [terpesthai]?” |171 Then you, all of you [Maidens of Delos], must very properly respond [hupokrinasthai], without naming names [aphēmōs]: [47] |172 “It is a blind man, and he dwells in Chios, a rugged land.” [[end of quotation by Thucydides, who now resumes his own comments]] {189|190}

|3.104.6 So much for the evidence given by Homer concerning the fact that there was even in the remote past a great coming together and festival [heortē] at Delos; later on, the islanders [nēsiōtai] and the Athenians continued to send choruses [khoroi], along with sacrificial offerings, but various misfortunes evidently caused the discontinuation of the things concerning the competitions [agōnes] and most other things—that is, up to the time in question [= the time of the ritual purification] when the Athenians set up the [quadrennial] competition [agōn], including chariot races [hippodromiai], which had not taken place before then.

Thucydides 3.104.3–6 [48]

Special note: as in the other ten passages in the sequence of Extracts 4-A through 4-K, I highlight here the contexts of terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ at lines 146 and 170 of the Homeric Hymn as quoted here.

4§40. The two sequences of verses here, as quoted by Thucydides and as attributed by him to Homer himself as the speaker of these verses, correspond to the following sequences of verses transmitted by the medieval manuscript traditions of the Homeric Hymn (3) to Apollo:

Extract 4-H

|146 But you, O Phoebus [Apollo], in Delos more than anywhere else feel delight [terpesthai] in your heart [ētor], |147 where the Ionians, with tunics [khitōn plural] trailing, gather |148 with their children and their {190|191} circumspect wives. |149 And they with boxing and dancing [orkhēthmos] and song [aoidē] |150 have you in mind and make you feel delight [terpein], whenever they set up a competition [agōn].

Homeric Hymn (3) to Apollo 146–150 [49]

Special note: as in the other ten passages in the sequence of Extracts 4-A through 4-K, I highlight here the context of terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ at line 146.

Extract 4-I

|165 But come now, may Apollo be gracious, along with Artemis; |166 and you all also, hail [khairete] and take pleasure, all of you [Maidens of Delos]. Keep me, even in the future, |167 in your mind, whenever someone, out of the whole mass of earthbound humanity, |168 arrives here [to Delos], after arduous wandering, as a guest entitled to the rules of hosting, and asks this question: |169 “O Maidens, who is for you the most pleasurable of singers |170 that wanders here? In whom do you take the most delight [terpesthai]?” |171 Then you, all of you [Maidens of Delos], must very properly respond [hupokrinasthai] about me [aph’ hēmeōn]: |172 “It is a blind man, and he dwells in Chios, a rugged land.”

Homeric Hymn (3) to Apollo 165–172 [50]

Special note: as in the other ten passages in the sequence of Extracts 4-A through 4-K, I highlight here the context of terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ at line 170.

4§41. At line 171 of this version as we find it in the medieval manuscript tradition, I show the variant reading aph’ hēmeōn (ἀφ’ ἡμέων). There are other corresponding variant readings also attested in the manuscripts, but I single out this one because it is comparable in its formulaic function to the variant reading aphēmōs (ἀφήμως) that we have already seen in the version quoted by Thucydides. I translate the variant reading aph’ hēmeōn (ἀφ’ ἡμέων) as ‘about me’, to be contrasted with the variant reading aphēmōs (ἀφήμως), which I translated as meaning ‘without naming names’. As I will argue, both aph’ hēmeōn and aphēmōs are authentic formulaic variants, and both of them are relevant to the {191|192} role of Homer as lead singer. In both versions, as we will see, the context is opaque and riddling.

The riddling of Homer in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo

4§42. In the case of the variant aph’ hēmeōn at line 171 of the Homeric Hymn to Apollo in a version that survives in the medieval manuscript tradition, as we read it in Extract 4-I, my translation ‘about me’ is a cover for the deeper meaning of this expression, which is ‘by me’. As I will argue, the Maidens of Delos are being prompted ‘by me’ to respond dialogically to a question ‘about me’. [51] And the reference to ‘me’ here, as we will see, is a riddling way of referring to Homer himself. The wording of Homer is coming ‘from me’ and is thus worded ‘by me’ to become the wording ‘about me’.

4§43. Similarly in the case of the variant aphēmōs in the version of line 171 quoted by Thucydides, as we read in in Extract 4-G, the meaning ‘without naming names’ signals the fact that the Maidens are being prompted to identify Homer in a riddling way, without naming him directly. [52]

4§44. And who are these Maidens of Delos, so prominently featured here in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo? As I argue in the book Homer the Classic, the Hymn pictures the Maidens as the local Muses of Delos who sing-and-dance as a prototypical chorus, which is parallel to the picturing of Homer as a prototypical lead singer. [53]

4§45. In this context of choral performance, I highlight the fact that the Delian Maidens in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo are described as masters of mimesis or ‘re-enactment’ (verb mīmeîsthai at verse 163). [54] This reference is saying something that is fundamentally true about choral performance in general, which as we know from the surviving textual evidence is highly mimetic. A shining example is the extant body of choral “lyric” songs composed by Pindar in the fifth century BCE. [55]

4§46. At a later point in my argumentation, I will elaborate on the mimetic power of Pindar’s songs. For now, however, I extend the analysis from the {192|193} medium of choral performance to another medium. What I just said about choral performance applies to the medium of rhapsodic performance as well: this medium too is highly mimetic. A most striking example is the interaction of Homer with the Delian Maidens in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo. In this hymn, as we will now see, the rhapsodic medium is making a mimesis of the choral medium.

4§47. When I say rhapsodic here, I am referring to a non-choral medium of performance, which is a medium that is not sung-and-danced and not even sung—but recited. As I already noted in Part One, this medium of recitative performance was practiced by professional performers known as rhapsōidoi ‘rhapsodes’, who both competed and collaborated with each other in the performance of epic at Panhellenic festivals like the Panathenaia in Athens. I have studied this rhapsodic medium extensively in other projects, especially in the 2002 book Plato’s Rhapsody and Homer’s Music, and I present here only a brief summary of what is relevant to my ongoing argument. [56]

4§48. Presiding over the rhapsodic competitions at the festival of the Panathenaia, as we know from a fleeting reference in Plato’s Ion (Ion 530d), were the Homēridai, who were a corporation of epic performers stemming from the island of Chios and claiming to be descended from Homer himself. [57] These Homēridai, masters of rhapsodic performance, also performed hymns. Unlike other hymns, which were conventionally performed in a choral mode, the hymns of the Homēridai were composed as well as performed only in a rhapsodic mode, as characterized by a single meter known as the dactylic hexameter. And it is these hymns that have survived down to our time in a collection of hexametric hymns that we now call the Homeric Hymns. As for the choral mode of composing and performing hymns, it too has survived—in the form of choral “lyric” singing, characterized by a vast multiplicity of meters. I have already highlighted the example of choral “lyric” songs composed by Pindar in the fifth century BCE. As we will now see, the Homer of the Homeric Hymn to Apollo performs a mimesis of such a non-rhapsodic choral mode of singing when he interacts with the chorus of the Delian Maidens—though this interaction is composed in the rhapsodic medium of the dactylic hexameter.

4§49. In the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, Homer re-enacts the Maidens by quoting what they say, which is said not in their own choral medium but in the rhapsodic medium of the Hymn. [58] So the medium of rhapsodic performance shows that it can make a mimesis of the medium of choral performance as exemplified by the Delian Maidens, who are described as the absolute masters of choral {193|194} mimesis. This way, Homer demonstrates that he is the absolute master of rhapsodic mimesis. [59]

4§50. The argument can be taken further: the figure of Homer in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo is acting as a lead singer when he prompts the Delian Maidens to perform a response, in choral song-and-dance, to a question. As we will see, the question will be a perennial one, just as the response of the Maidens will be perennial.

4§51. To understand this question that is addressed to the Delian Maidens, we need to consider the entire context of the dialogue that takes place between them and Homer. The complete wording of this dialogue is not quoted by Thucydides, and we find it attested only in the medieval manuscript tradition of the Homeric Hymn to Apollo. I now quote here the complete wording as preserved in that textual tradition:

Extract 4-J (including lines 165–172 as quoted already in 4-I)

|165 But come now, may Apollo be gracious, along with Artemis; |166 and you all also, hail [khairete] and take pleasure, all of you [Maidens of Delos]. Keep me, even in the future, |167 in your mind, whenever someone, out of the whole mass of earthbound humanity, |168 arrives here [to Delos], after arduous wandering, as a guest entitled to the rules of hosting, and asks this question: |169 “O Maidens, who is for you the most pleasurable of singers |170 that wanders here? In whom do you take the most delight [terpesthai]?” |171 Then you, all of you [Maidens of Delos], must very properly respond [hupokrinasthai] about me [aph’ hēmeōn]: |172 “It is a blind man, and he dwells in Chios, a rugged land. |173 and all his songs will in the future prevail as the very best.” |174 And I [60] in turn will carry your fame [kleos] as far over the earth |175 as I wander, throughout the cities of men, with their fair populations. |176 And they will all believe—I now see— [61] since it is genuine [etētumon]. |177 As for me, I will not leave off [lēgein] making far-shooting Apollo |178 [the subject of] my hymn [humnos]—the one with the silver quiver, who was borne by Leto of the fair tresses.

Homeric Hymn (3) to Apollo 165–178 [62] {194|195}

Special note: as in the other ten passages in the sequence of Extracts 4-A through 4-K, I highlight here the context of terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ at line 170.

4§52. Our first impression is that the question addressed here to the Delian Maidens, as quoted directly at lines 169–170, is simple and straightforward: "'|169 O Maidens, who is for you the most pleasurable of singers |170 that wanders here? In whom do you take the most delight [terpesthai]?'" [63] And the response of the Maidens at line 172, as also quoted directly, seems likewise simple and straightforward: '"|172 It is a blind man, and he dwells in Chios, a rugged land.'" [64]

4§53. What complicates both the question and the answer, however, is that the person who originally asks the question seems at first to be distinct from Homer. Homer seems at first to be simply quoting the question. The original questioner is described at line 168 as some nameless wanderer who will come to visit Delos in the future. Let us consider again lines 167–168 in the medieval manuscript tradition, where the nameless wanderer who addresses the question to the Delian Maidens is described in this way: "'|167 … whenever someone, out of the whole mass of earthbound humanity, |168 arrives here [to Delos], after arduous wandering, as a guest entitled to the rules of hosting, and asks this question …'" [65] So, it is as if someone other than Homer were asking the question quoted by Homer.

4§54. This complication is what turns both the question and the answer into a riddle, since the nameless questioner is kept distinct here from Homer, even though the description of this nameless person as a wanderer who claims the right to be treated as a guest makes him look as if he were Homer himself. After all, Homer too is a wanderer, just as the nameless questioner is a wanderer. And Homer is a wandering singer who claims the right to be treated as a guest at whatever place he visits, as we see later on at lines 174–175, where he describes in his own words the fame that he will create for the Delian Maidens: "|174 And I in turn will carry your fame [kleos] as far over the earth |175 as I wander, throughout the cities of men, with their fair populations." [66] {195|196}

4§55. Homer will create fame for the Delian Maidens as an act of reciprocation for the fame that the Maidens will create for Homer when they respond to the question in the words quoted by Homer himself. The difference is, the Maidens create fame for Homer in their role as singers-dancers who are stationary, while Homer creates fame for the Maidens in his role as a lead singer who is mobile, a wanderer. And Homer is the best of all wandering singers, as predicted by the wording of the question directly quoted at lines 169–170, where we read: '"|169 O Maidens, who is for you the most pleasurable of singers |170 that wanders here?…'" [67] This question already presupposes that Homer is that wandering singer. So, now the meaning loops back again to lines 167–168, where the person who addresses the question to the Delian Maidens is described in this way: "'|167 … whenever someone, out of the whole mass of earthbound humanity, |168 arrives here [to Delos], after arduous wandering, as a guest entitled to the rules of hosting, and asks this question …'" [68] By now we see that this nameless wanderer, even though he seemed at first to be distinct from Homer, must be identical with Homer. And he is pictured as returning to Delos year after year to ask a question that requires the same answer year after year, and that answer is ‘Homer’.

4§56. Similarly, as I have argued in the book Homer the Classic, even the alternative wording of line 168 of the Hymn as quoted by Thucydides about the "other someone" who comes to Delos leaves open the option of imagining that the "other someone" who asks the riddling question could still be the same singer returning again and again to Delos, and this singer could still be Homer, not a substitute for Homer. [69] The "other someone" is an "other" only so long as the identification is not yet made, since this "other" is nameless. But Homer does have a name, which is ostentatiously not spoken. If that name were in fact spoken, however, then the identification of the ‘other’ as Homer himself could become clear. But Homer is here being identified without being named. That, I argue, is the force of the riddling expression aphēmōs at verse 171 of the Homeric Hymn to Apollo as quoted by Thucydides: as I already noted, this expression means ‘without naming names’. So, the Maidens are being prompted by Homer to identify Homer in a riddling way, without naming him directly. [70]

4§57. What makes the riddle work is that Homer remains unnamed, just as the wanderer who is quoted as asking the question is not named. But the response of the Maidens, about that blind singer who dwells in Chios, gives away the answer: this wandering singer must be Homer, who is known to be blind and {196|197} who claims Chios as his residence. As we know from the Life of Homer traditions, which preserve evidence that is independent of the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, the blind singer who once resided in Chios can in fact be identified as Homer. I refer here to a detailed study of this evidence in the book Homer the Preclassic, where I focus on the evidence we can find in the Herodotean Life of Homer. [71]

4§58. So, the response of the Maidens as quoted at lines 172–173 of the Homeric Hymn to Apollo can be seen as a mimesis of Homer by Homer about Homer; and, to complicate matters further, this mimesis is performed for Homer by the Maidens of Delos, whose existence in the song is a mimesis by Homer because it is Homer who quotes what they say. [72] In a sense, then, the whole performance originates from this lead singer. And that, I argue, is the force of the complex expression aph’ hēmeōn at verse 171 of the Hymn: the Maidens are prompted ‘by me’ to respond dialogically to a question ‘about me’, and the prompt originates ‘from me’. [73]

Homer’s eternal return to Delos in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo

4§59. The riddling dialogic response of the Delian Maidens to Homer is made perennial by their recurrent choral performance in response to the recurrent visit of Homer to Delos in his role as their lead singer. According to the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, the performance of Homer in choral interaction with the Maidens of Delos will become a perennial event. In terms of the myth that we see encapsulated in the Hymn, there will be an eternal return of Homer to Delos.

4§60. To back up this formulation, I will show that the Homeric Hymn to Apollo foretells in a riddling way a seasonally recurring re-enactment of the prototypical visit of Homer to Delos. The visit will be re-enacted year after year, in a loop that loops back eternally, so that Homer may forever interact with succeeding generations of young women who will re-enact in song-and-dance the prototypical Maidens of Delos in the act of chorally responding to Homer about Homer for Homer.

4§61. As we will now see, the occasion for Homer’s eternal return to Delos was the annual festival of the Delia, and the word that signals this festival in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo is agōn, which as I already noted means ‘competition’. {197|198}

Homer as the lead singer at an agonistic choral event

4§62. In Odyssey viii 250–269, quoted in Extract 4-E, we have seen the figure of Demodokos performing as a lead singer who interacts with a chorus that is singing-and-dancing at a competitive choral event, and the word for this event at lines 259 and 260 is agōn, meaning ‘competition’. Here again is the wording: "|259 … they started arranging everything according to the rules of the competition [agōn]: |260 they made smooth the place of the singing-and-dancing [khoros], and they made a wide space of competition [agōn]." [74] So too in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo we see the figure of Homer himself performing as a lead singer in his own right, and he too is interacting with a chorus that is singing-and-dancing at a competitive choral event called an agōn. That is what I will show here, arguing that the figure of Homer qualifies as a lead singer in the context of such an agōn. Or, to put it in terms of a modern word derived from agōn, Homer is a lead singer at the agonistic choral event of the Delia.

4§63. If we look back at the lengthy passage I quoted from Thucydides (3.104.3–6) in Extract 4-G, we can see that the historian uses this word agōn with reference to both choral and athletic competitions at the festival of the Delia (3.104.3 [choral], 3.104.5 [choral and athletic], 3.104.6 [choral and athletic]). As we can see further in Extract 4-G, Thucydides also quotes from the Homeric Hymn to Apollo a passage that features the same word agōn with reference to both choral and athletic competitions at the festival of the Delia: in one of the lines (149) quoted from the Hymn, the words orkhēstus ‘dancing’ and aoidē ‘singing’ indicate the choral competition, while the word pugmakhiē ‘boxing’ indicates one example of the various athletic competitions. The same three words, with one slight formal variation (orkhēthmos instead of orkhēstus for ‘dancing’), are also attested in the corresponding line (149) of the version found in the medieval manuscripts of the Hymn to Apollo and quoted in Extract Q. From here on, whenever I refer to competitive choral events, I will substitute the term agonistic for competitive in order to evoke the meaning of agōn as this word is used in the contexts we have just considered.

4§64. In the case of Odyssey viii, the agonistic choral event is ostentatiously festive, as we have already seen from my overall paraphrase of the relevant narrative, but it cannot be tied to any specific festival. In the case of the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, by contrast, the corresponding agonistic choral event is pictured as taking place on a very specific occasion, at the festival of the Delia in Delos. And the choral aspect of this agonistic event that took place at the seasonally {198|199} recurrent festival of the Delia is highlighted by Thucydides: he uses the word khoros ‘chorus’ in referring to female singers-and-dancers who performed at this festival (3.104.3, 3.104.5, 3.104.6). It is clear that Thucydides, in analyzing the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, imagined that Homer himself had once interacted with a prototypical khoros of these female singers-and-dancers (3.104.5), and it is also clear that he connected this prototypical khoros with the historical attestations of agonistic choral events that were taking place at the annual festival of the Delia (3.104.3, 3.104.6). This connection made by Thucydides is justified, since the Homeric Hymn in its own wording connects the Maidens of Delos with an agonistic choral event that is celebrated at the festival of the Delia in Delos. Highlighted in the Hymn, as I already noted, are the words orkhēstus/orkhēthmos ‘dancing’ and aoidē ‘singing’ (line 149). And here I return to a comparable highlighting in Odyssey viii, with reference to the skills of the Phaeacian youths in choral as well as athletic competitions (248–253): among the words that we see in this context are khoroi ‘choruses’ (248), orkhēstus ‘dancing’ (253), and aoidē ‘singing’ (253). And we have also seen the word khoros in the specific context of referring to the place of the singing-and-dancing (260).

4§65. In Odyssey viii, the reaction of all those who attend such an agonistic choral event is delight, as expressed by the verb terpesthai, meaning ‘feeling delight’, and such a reaction is best exemplified by the disguised Odysseus as the primary character attending the performance of Demodokos in concert with the choral singers-dancers: it is said that Odysseus, in reacting to this performance, terpeto ‘felt delight’ (368), and the same delighted reaction was experienced, it is also said, by everyone else attending the performance (368–369). Again in Odyssey xiii, where Demodokos is performing as a lead singer for the last time, the entire community is described as terpomenoi ‘feeling delight’ (27), as we saw in the passage I quoted in Extract 4-F.

4§66. And there is a comparable reaction in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo: at lines 146–150, which I have already quoted in Extract 4-G, the Ionian Greeks who celebrate the festival of the Delia, which is called an agōn here (150), are delighting Apollo himself: as Homer says to the god, these celebrants ‘give you delight’, terpousin (again, 150), precisely because they are celebrating the festival by way of both choral and athletic competitions (149). As the principal god who presides over the festival of the Delia, Apollo is told by Homer that ‘you feel delight’, epi-terpeo, at each recurring occasion when the festival is celebrated. Here again is the wording of the relevant lines 146–150 in the Hymn, which I quoted already in Extract 4-G: "|146 But when, O Phoebus [Apollo], in Delos more than anywhere else you feel delight [terpesthai] in your heart [thūmos], |147 there the Ionians, with tunics [khitōn plural] trailing, gather |148 with their children and their wives, along the causeway [aguia], |149 and there with boxing [pugmakhiē] {199|200} and dancing [orkhēstus] and song [aoidē] |150 they have you in mind and make you feel delight [terpein], whenever they set up a competition [agōn]." [75] The same wording, with minor variations, is attested in the corresponding text of the medieval manuscripts, and I have already quoted that text in Extract 4-H.

4§67. So the god Apollo, as a god, is the perfect model for everyone who attends the festival of the Delia: he reacts to the beauty and the pleasure of the Hymn to Apollo by feeling utter delight. We can see in this reaction another example of the theological principle of do as I do. [76] And the god’s reaction is re-enacted by the Delian Maidens when they identify Homer, without naming him, as the one who surpasses all other singers in making them too feel delight, just as Homer makes everyone feel delight. Already the question asked by the nameless singer makes it clear that the ultimate purpose of Homer is to give that feeling of delight to all: "'|169 O Maidens, who is for you the most pleasurable of singers |170 that wanders here? In whom do you take the most delight [terpesthai]?'" [77] That singer, as the response of the Delian Maidens indicates in its own riddling way, must be identified as Homer.

Homer and Demodokos as masters of hymnic singing

4§68. We have just seen, then, how the Homeric Hymn to Apollo idealizes the sheer delight that must surely be felt by all when they hear Homer himself singing at the agonistic choral event of Apollo’s festival, the Delia. In the Hymn, a clear signal of this idealization is the programmatic use of the word terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ (146, 150, 170) in describing the reaction to Homer’s song. Also in Odyssey viii, we have seen the same programmatic use of this word terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ in describing the reaction of all those who hear the song of Demodokos about Ares and Aphrodite (368–369). And the key word for referring to the form of singing that we see being performed in both these cases is humnos, which I have translated so far simply as ‘hymn’. As the argumentation advances, we will see that both Homer and Demodokos are masters of such hymnic singing.

4§69. Essential for my argument is an extraordinary single line, Odyssey viii 429, referring to the singing of a humnos by Demodokos. Nowhere else in the Odyssey—or in the Iliad, for that matter—is this word humnos attested. For the moment, I translate the line without translating the word humnos itself: {200|201}

Extract 4-K

… so that he [= Odysseus] may feel delight [terpesthai] at the feast [dais] and in listening to the humnos of the song.

Odyssey viii 429 [78]

Special note: as in the other ten passages in the sequence that comes to an end with this passage, Extract 4-K, I highlight here the context of terpesthai ‘feeling delight’.

An idealization of the delight experienced at a festival

4§70. The context of line 429 in Odyssey viii is this: at lines 424–428, Alkinoos is speaking of his plans for the further hosting of his guest Odysseus, who has not yet identified himself. As a gracious host, Alkinoos says that he wants to arrange for his guest to be bathed in a lustral basin and then to be clothed in luxurious new garments before they all sit down to dine together, at which occasion Odysseus will receive going-away presents. The syntax of the expression ‘so that he may feel delight [terpesthai] ’ at line 429 carries two levels of meaning here, since the host’s wish is both general and specific. Generally, the guest should be gratified by the good hosting. But there is also the specific gratification of dining well while hearing the performance of song. The idea of dining at line 429, as expressed by the word dais, meaning ‘feast’, is closely combined here with the idea of hearing the performance of ‘song’, as expressed by the word aoidē together with humnos, and this combination is viewed as the best of all gratifications. In this same line 429, such sheer gratification is signaled by the programmatic word terpesthai, ‘feeling delight’. As I will now argue, what we see here is an idealization of the experience of ‘feeling delight’ in the context of a dais ‘feast’, which in turn is an idealization of a festival.

4§71. As Odysseus himself says later on in Odyssey ix, when he finally identifies himself, there is in fact no greater gratification in the whole world than the combination of good feasting and good singing, and the model for the general reference to singing here is the singer Demodokos:

Extract 4-L

|3 This is indeed a beautiful thing, to listen to a singer [aoidos] |4 such as this one [= Demodokos], the kind of singer that he is, comparable to the gods with the sound of his voice [audē], |5 for I declare, there is no {201|202} outcome [telos] that has more pleasurable beauty [kharis] |6 than the moment when the spirit of festivity [euphrosunē] [79] prevails throughout the whole community [dēmos] |7 and the people at the feast [daitumones], throughout the halls, are listening to the singer [aoidos] |8 as they sit there—you can see one after the other—and they are seated at tables that are filled |9 with grain and meat, while wine from the mixing bowl is drawn |10 by the one who pours the wine and takes it around, pouring it into their cups. |11 This kind of thing, as I see it in my way of thinking, is the most beautiful thing in the whole world.

Odyssey ix 3–12 [80]

4§72. The feast that is going on here is a continuation of the feast that is already signaled by the word dais at line 429 of Odyssey viii, quoted in Extract 4-K, which basically means ‘feast’. In that context, dais refers short-range to an occasion of communal dining (dorpon ‘dinner’: 395), which will take place after sunset (417). The intended guest of honor at this feast will be Odysseus. This occasion of communal dining leads into the third song of Demodokos (484–485). But this same word dais at line 429 of Odyssey viii is also making a long-range reference: it refers metonymically to a stylized festival that has been ongoing ever since an earlier occasion of communal dining (71–72), which actually led into the first song of Demodokos (73–83). And let me go even further back in time. Leading up to the communal dining, there had been an animal sacrifice (as expressed by the word hiereuein ‘sacrificially slaughter’: 59). Then, the meat of the sacrificed animals (twelve sheep, eight pigs, and two oxen: 59–60) had been prepared to be cooked at the feast (61). And I stress that the word at line 61 for ‘feast’ is once again dais.

4§73. The noun dais ‘feast’ is derived from the verb daiesthai in the sense of ‘distribute’, which is used in contexts of animal sacrifice in referring to the ‘distribution’ of cooked meat among the members of a community (as in Odyssey xv 140 and xvii 332). Then, by way of synecdoche, the specific idea of distribution extends metonymically to the general idea of feasting and further to the even more general idea of a festival. Following the logic of this sequence of meanings, we see that the animal sacrifice in Odyssey viii (59) had led to the cooking and {202|203} the distribution of the meat (61), which had led to the communal dining (71–72), which had led to the first song of Demodokos (73–83), and so on. In terms of this logic, the metonymic use of the word dais ‘feast’ marks a whole complex of events that are typical of festivals: animal sacrifice, communal feasting, singing as well as dancing at the feast. [81]

4§74. Besides these events in Odyssey viii, we find another set of events that are likewise typical of festivals. Right after the first song of Demodokos has come to an end (83), the king of the Phaeacians announces that there will now be a pause in the eating and the drinking, to which he refers generally as a dais ‘feast’ (98 and 99), and the pause extends to the singing that has so far accompanied the dais (99). The time has come for athletic contests, that is, aethloi/aethla (100), to be held outside the palace, in the public gathering space of the Phaeacians (100–101, 109). The king refers to boxing, wrestling, jumping, and footracing (103). The first athletic event turns out to be the footrace (120–125), followed by wrestling (126–127), jumping (128), discus throwing (129), and boxing (130). The general term that refers to the occasion of all these events is agōn, meaning ‘competition’ or ‘place of competition’ (200, 238).

4§75. There is a striking parallel to be found in a passage we have already examined in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo (146–155), describing a festival of all Ionians gathered on the island of Delos. In this case as well, the occasion of that Delian festival is described as an agōn ‘competition’ (149). The competitive events at that festival include athletics—boxing is the example that is highlighted—as well as dancing and singing (149). Similarly in Odyssey viii, the competition includes singing as well as athletics, as we see from the fact that the three songs performed by Demodokos become a foil for the later performance of Odysseus starting in Odyssey ix. And the occasion for the singing of Demodokos in Odyssey viii, as we have already seen, is the ongoing dais ‘feast’ (429), which is a stylized festival—and which continues to be the occasion for the competitive performance of Odysseus in Odyssey ix. [82]

4§76. For the moment I concentrate not on the singing but on the athletics. As in the case of singing, athletics too can be seen as a source of ‘feeling delight’, terpesthai, to be experienced at a festival. I cite yet again the relevant lines 146–150 in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, as quoted in Extract 4-G, concerning the festival of the Delia: ‘|146 But when, O Phoebus [Apollo], in Delos more than anywhere else you feel delight [terpesthai] in your heart [thūmos], |147 there the Ionians, with tunics [khitōn plural] trailing, gather |148 with their children and their wives, along the causeway [aguia], |149 and there with boxing [pugmakhiē] {203|204} and dancing [orkhēstus] and song [aoidē] |150 they have you in mind and make you feel delight [terpein], whenever they set up a competition [agōn]’. [83]

The relevant etymology of a Hittite word

4§77. The idea of ‘feeling delight’ on a festive occasion, as expressed by the Greek verb terpesthai, is built into a related form that we find attested in the Hittite language. It is the noun tarpa -, attested in a Hittite text dating from the second millennium BCE. This particular text (Keilschrifttexte aus Boghazköi XXIII 55 I, 2–27), analyzed by Jaan Puhvel, is describing a festive occasion. There is to be an animal sacrifice (four rams and an unspecified number of bulls), and there are athletic events, which include boxing and wrestling. As Puhvel notes, “a military gathering in the iconic presence of the solar deity seems to be the occasion.” [84] And the word that refers to this occasion is tarpa-. This word, Puhvel suggests, “would then be the ‘pleasure part’ of the event, the distribution, celebration, and enjoyment of winnings, perhaps even etymologically cognate with the Greek terp[esthai], ‘to delight’, which crops up so often in the Homeric vocabulary of sports.” [85]

4§78. In making this argument, Puhvel cites a number of Homeric lines that feature this word terpesthai, and among them is line 131 of Odyssey viii, where the Phaeacians are said to be ‘feeling delight’ in response to the spectacular aethloi/aethla or ‘contests’ that are then taking place. These contests are athletic competitions, which as we have just seen are imagined as part of the ongoing festivities that are narrated in Odyssey viii. At line 131, the word terpesthai ‘feeling delight’ focuses on athletics as one particular aspect of the festivities, whereas later on at line 429, as quoted in Extract 4-K, the same word focuses on another aspect, which is the singing of Demodokos. In both lines, the overall context is a stylized festival.

The festive context of hymnic singing

4§79. I now turn to the humnos that Demodokos is singing at line 429 of Odyssey viii. As we have just seen in the same line, the overall context for this singing is a stylized festival, signaled by the word dais ‘feast’. This festive context, as we will now see, is the key to understanding what the word humnos means here. {204|205}

4§80. As I showed in the book Homer the Classic, this word humnos fits all the forms of singing performed by Demodokos at the ongoing festival narrated in Odyssey viii, including the song that he finishes performing at line 367, which is a story about Ares and Aphrodite. [86] As I also showed in that book, the morphology of this particular song is cognate with the morphology of the so-called Homeric Hymns, including the Homeric Hymn to Apollo. [87] And, as we will see, many of the Homeric Hymns actually refer to themselves in terms of humnos. This is not to say, however, that the translation of humnos as ‘hymn’ is sufficient for helping us understand the combination of this noun with the genitive of the noun aoidē at line 429 of Odyssey viii, where Alkinoos expresses the wish that Odysseus ‘may feel delight [terpesthai] at the feast [dais] and in listening to the humnos of the song [aoidē]’. We are still left with the problem of translating humnos in the actual context of a ‘humnos of the song [aoidē]’. Here is where I shift from the figure of Demodokos as a master of hymnic singing to the figure of Homer as represented in the Homeric Hymns, especially in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo. Homer too, as we will now see, is a master of hymnic singing.

A metonymy of hymning

4§81. The English words hymn/hymnic/hymning derive from the programmatic use of the Greek word humnos in poetry as exemplified by the Homeric Hymns. Each one of these Hymns is addressed to a god or goddess who notionally presides over the performance of the hymn, and this link to divinity is in fact the key to the meaning of humnos. As we will see from attestations of this word in the Hymns, a humnos is seen as a perfect beginning of a perfect song. And the beginning is perfect if the divinity to whom the song is addressed favors the performance of the beginning. But the humnos is not just a perfect beginning. It is also the signal of a perfect transition to the rest of the performance. By metonymy, the humnos includes the rest of the performance, proceeding sequentially all the way to the conclusion of the whole performance. If the performance is sequential, consequential, you know it was started by a humnos and you know it is really a humnos. [88]

The hymnic subject

4§82. To analyze further the programmatic use of the word humnos in the Homeric Hymns, I find it useful to introduce a relevant term, the hymnic subject. In the Homeric Hymns, the invoked divinity who presides over a given festival is the {205|206} hymnic subject of the hymn. In the language of the Hymns, however, the divinity who figures as the subject of any hymn is normally the grammatical object of the verb of singing the hymn (as at the beginnings of Homeric Hymns 2, 4, 6, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21, 23. 26, 27, 28, 30, 31, 32). In the logic of the Hymns, the hymnic subject is the divinity that presides over the occasion of performance and becomes continuous with the occasion and thus becomes the occasion. [89]

A theology of perfection in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo

4§83. The occasion of a humnos is notionally perfect because the divinity who is the occasion is perfect. The theological notion of such perfection is expressed by way of the word eu-humnos (εὔυμνος) ‘good for hymning’, as in the sublime aporetic question that is asked twice in the Homeric Hymn (3) to Apollo (verses 19 and 207): [90]

Extract 4-M

For how shall I hymn you, you who are so absolutely [pantōs] good for hymning [eu-humnos]?

Homeric Hymn (3) to Apollo 19 and 207 [91]

4§84. The theological rationale of this aporetic question can be formulated this way:

Faced with the absoluteness of the god, the performer experiences a rhetorical hesitation: how can I make the subject of my humnos something that is perfect, absolute? The absoluteness of this hymnic subject is signaled by the programmatic adverb pantōs ‘absolutely’, which modifies not only the adjective eu-humnos ‘good for hymning’ but also the entire phrasing about the absoluteness of the subject. The absoluteness of the god Apollo is continuous with the absoluteness of the humnos that makes Apollo its subject. This Homeric Hymn is saying about itself that it is the perfect and absolute humnos. As such, it is not only the beginning of a composition but also the totality of the composition, authorizing everything that follows it, because it was begun so {206|207} perfectly. And the source of the perfection is the god as the subject of the humnos. [92]

4§85. The naming of the divinity as the subject of the humnos, together with the initial describing of the divinity, is the notionally perfect beginning of the humnos, and this beginning is the prooimion. We have already seen in Extract 4-G that Thucydides refers to the Homeric Hymn to Apollo explicitly as a prooimion (3.104.4, 5).