-

Gregory Nagy, Masterpieces of Metonymy: From Ancient Greek Times to Now

Acknowledgments

List of Extracts

Introduction

I: Making metonyms both naturally and artistically

II: Interweaving metonymy and metaphor

III: Masterpieces of metonymy on the Acropolis

IV: The metonymy of a perfect festive moment

Epilogue without end: A metonymic reading of a love story

Bibliography

Part Three: masterpieces of metonymy on the Acropolis

3§01. By now we have seen many times and in many ways how the act of narrating the myth of the cosmic battle between the Olympians and the Giants was intrinsic to and inextricable from the seasonally recurring ritual of pattern-weaving the sacred robe or Peplos of Athena in Athens. To narrate the sacred myth was to pattern-weave it into the sacred Peplos. [1] This seasonally rewoven Peplos, as I will argue here in Part Three, was meant to be the re-enactment of a perfect sacred model, which was the original work of pattern-weaving performed by the goddess Athena herself. The myth about that original pattern-weaving is highlighted in Iliad V 734–735, which I already quoted in Extract 2-R of Part Two. In that context, I described Athena’s masterpiece of pattern-weaving as a perfect masterpiece of metonymy, and I must review here why I said it that way. It is because, as I argued in Part Two, the mechanical process of pattern-weaving a peplos was actually driven by a metonymic way of thinking, and so the pattern-weaving of the Peplos of Athena by Athena would surely have resulted in something that is considered to be absolutely perfect—a perfect masterpiece of metonymy.

3§02. Here in Part Three, I will argue further that this original Peplos of Athenian myth, this masterpiece of metonymy, actually became a model for the marvels of visual art that honored the goddess Athena in her sacred space situated on top of the Acropolis in Athens. In making this argument, I will correlate the physical evidence of such marvels with the actual myth about the making of the Peplos of Athena by Athena. What will stand out, I say already now, is the visual testimony of the sculptures adorning that ultimate marvel of the Athenian Acropolis, the Parthenon. On the basis of that visual testimony, I will argue that the Parthenon itself is in its own right another ultimate marvel—a perfect masterpiece of metonymy. {135|136}

Starting over with the robe woven by Athena

3§1. I return here to the two lines of Iliad V 734–735 that I quoted in Extract 2-R of Part Two. As we learned when we first looked at those two Homeric lines, the wording there says explicitly that the goddess Athena herself pattern-wove with her own hands the Peplos that she herself was wearing at the exact moment when she entered the war between the Achaeans and the Trojans in the Iliad.

3§2. Now the time has come for me to consider the larger context of the Homeric passage that frames these two lines, and I will argue that this framing passage, extending from verse 733 to verse 747 in Iliad V, combines the fundamental idea that Athena wove her own peplos with a further fundamental idea, that she actually narrated the Gigantomachy by way of pattern-weaving her narration into her peplos. And, as I will also argue, the poetic combination of these two fundamental ideas leads to the artistic creation of a Homeric masterpiece of metonymy that matches the Peplos itself as a metonymic masterpiece in its own right.

3§3. I now quote, in its entirety, the Homeric passage:

Extract 3-A (including the full text of the two lines 734–735 quoted in 2-R)

|733 As for Athena, daughter of Zeus who has the aegis, |734 she let her woven robe [peplos] slip off at the threshold of her father, |735 her pattern-woven [poikilos] robe, the one that she herself made and worked on with her own hands. |736 And, slipping into the tunic [khitōn] of Zeus the gatherer of clouds, |737 with armor she armed herself to go to war, which brings tears. |738 Over her shoulders she threw the aegis, with fringes on it, |739 —terrifying—garlanded all around by Fear personified. |740 On it [= the aegis] are Strife [Eris], Resistance [Alkē], and the chilling Shout [Iōkē, as shouted by victorious pursuers]. |741 On it also is the head of the Gorgon, the terrible monster, |742 a thing of terror and horror, the portent of Zeus who has the aegis. |743 On her head she put the helmet, with a horn on each side and with four bosses, |744 golden, adorned with pictures showing the warriors [pruleis] of a hundred cities. |745 Into the fiery chariot with her feet she stepped, and she took hold of the spear, |746 heavy, huge, massive. With it she subdues the battle-rows of men— |747 heroes against whom she is angry, she of the mighty father.

Iliad V 733–747 [2] {136|137}

3§4. I begin my analysis of this Homeric passage by highlighting two moments. One of these moments is when Athena is seen slipping out of her peplos or ‘robe’, and the other moment is when she is then seen slipping into a khitōn or ‘tunic’, which now becomes the undergarment for the suit of armor that she proceeds to put on her divine body. [3] But there is yet another moment, and it comes between these two delimiting moments. In that intervening moment, as I observed in an earlier analysis of this passage featuring Athena’s arming scene, “there is room for the thought—if not the image—of the goddess in the nude.” [4] In that analysis, I went on to compare the thinking of Friedrich Nietzsche when he speaks ‘about that one nude goddess’, um jene eine nackte Göttin, who is somehow the essence of Wissenschaft or ‘learning, knowledge’. [5] Even if Nietzsche may not have in mind the Homeric context that I am analyzing here, it seems to me that his wording is a perfect fit for the goddess Athena as we see her in this one truly singular moment.

3§5. That fleeting thought about the goddess in the nude can be connected, as we will see later, to a detail we find embedded in Athenian myths and rituals linked with Athena—a detail that I will introduce at a later point here in Part Three. For now, however, I focus on the actual moment that intervenes between the earlier moment when the goddess slips out of her peplos and the later moment when she slips into her khitōn—into that divine tunic that now becomes the undergarment for her suit of armor. In my earlier analysis, I had this to say about that singular intervening moment:

Even as the thought [of a nude goddess] flashes by, the Homeric picturing of Athena in motion moves on, without a blink, from a vision of the goddess in a peplos to a vision of the goddess in a khitōn. So there is a complementarity in Athena’s wearing a peplos at one moment and in her wearing a khitōn at the next moment. [6]

3§6. The peplos that Athena takes off in Iliad V 734 ‘at the threshold of her father’ connects her to her identity as a model weaver, since the wording here {137|138} says explicitly that she wove this robe herself, while the khitōn that she puts on her divine body as she readies herself to engage in war at V 736–737—a khitōn that belongs to her father Zeus, as the Homeric wording says explicitly—connects her to her identity as a model warrior. [7] As we will now see, this complementarity of the peplos and the khitōn worn by Athena from one moment to another in Athena’s arming scene at Iliad V 733–747 is matched by the complementarity of her two roles in the myths and rituals of the city of Athens. And these two roles are linked with the two primary statues of Athena that were housed on top of the Acropolis of Athens in the classical period of the mid-fifth century BCE, that is, in the age of Pheidias the sculptor. I now offer a brief description of these two statues of the goddess.

3§7. On the one hand, there was the classical statue of Athena the Virgin, the Parthénos, sculpted by Pheidias himself, which was housed in the classical temple known as the Parthenon. We have an eyewitness description of the statue, dating back to the second century CE, from the traveler Pausanias. As we will see from his wording, which I am about to quote, the appearance of this statue corresponds closely to the Homeric vision of Athena as a model warrior. As we saw in Iliad V 733–747, quoted in Extract 2-A, Athena at line 736 wears the khitōn or ‘tunic’ of his father as an undergarment for her suit of armor. So also, as we are about to see, the statue of Athena in the Parthenon was wearing her armor over an ankle-length khitōn. And, likewise corresponding to the Homeric description of Athena’s arming scene, the statue as described by Pausanias showed Athena carrying a spear and wearing both a helmet and the feared aegis, which featured the head of the Gorgon Medusa. I quote here the description of Pausanias:

Extract 3-B

The statue [agalma] itself is made of gold and ivory. In the middle of the helmet is placed a likeness of the Sphinx. [Pausanias here gives a cross-reference to an excursus of his, deployed at a later point in his work, about the Sphinx.] On each side of the helmet there are griffins worked in. […] |7 […] The statue [agalma] of Athena is standing, wearing a tunic [khitōn] that extends to her feet. On her chest is the head of Medusa, made of ivory. She has [in one hand] a [figure of] Nike, around four cubits in height, and she holds in her [other] hand a spear. A shield [aspis] is positioned at her feet. And near the spear is a serpent [drakōn]. Now this serpent [drakōn] would be Erikhthonios. And on the surface of the base of the statue is a relief of the genesis of Pandora. The story of {138|139} the genesis of this first woman Pandora is told by Hesiod in his poetry as well as by others.

Pausanias 1.24.5–7 [8]

3§8. So much for the statue of Athena Parthénos, housed in the Parthenon. On the other hand, there was the preclassical statue of Athena Polias, the ‘goddess of the city’, which was housed in the old temple of the goddess. Whereas the statue of Athena Parthénos in the Parthenon was shown wearing a khitōn, the statue of Athena Polias was associated with a peplos. But the peplos of this preclassical Athena Polias residing in the old temple, unlike the khitōn of the classical Athena Parthénos residing in the Parthenon, was not sculpted into her own statue. As we have already seen, the peplos of Athena Polias was instead pattern-woven for her, year after year, [9] and the pattern that was woven into this peplos of the goddess was a narration of the Gigantomachy, which was a charter myth for the Athenians. [10]

3§9. Here I return to the complementarity of the peplos and the khitōn worn by Athena from one moment to the next in Athena’s arming scene at Iliad V 733–747, as quoted in Extract 3-A. As we can see by now, this complementarity is matched by the complementarity of Athena’s two roles in the myths and rituals of the city of Athens. As the resident of the old temple, on the one hand, the goddess was connected with the weaving of the peplos—for her to wear. As the resident of the new temple, on the other hand, she was connected with the wearing of a khitōn under her divine armor.

3§10. This match in complementarity does not mean, of course, that the Homeric passage we have read was somehow based on the myths and rituals of Athens as they existed in the classical era, that is, in the fifth century BCE, when the new temple of the Parthenon and the new statue of Athena Parthénos as its resident virgin warrior goddess were inaugurated. After all, the very idea of Athena as a warrior goddess was clearly preclassical: it was older, far older, than the classical statue that became the definitive visual realization of the goddess housed in the Parthenon. And the idea of Athena Polias was likewise preclassical, just as the statue of Athena Polias housed in the old temple was preclassical. {139|140}

3§11. On the other hand, the match in complementarity between Iliad V 733–747 and the realia of Athenian myths and rituals does in fact indicate that this Homeric passage reflects at least a preclassical Athenian phase in the evolution of Homeric poetry. The argument for the existence of such an earlier phase, dating back to the sixth century BCE, has been laid out in my twin books Homer the Classic and Homer the Preclassic. Already during the preclassical phase of Homeric poetry, in terms of my argumentation, Athenians would be attending performances of the Iliad and the Odyssey at the festival of the quadrennial Panathenaia, and a Homeric reference to the charter myth of the Panathenaia in Iliad V 733–747 would be seen by them as a ringing validation of their all-important festival.

A Homeric masterpiece of metonymy

3§12. Having noted the preclassical Athenian agenda at work in the Homeric passage I quoted from Iliad V 733–747 in Extract 3-A, I return to my focus on the complementarity of the two aspects of Athena in classical as well as preclassical Athens: on the one hand, we have seen the goddess as the recipient of the Panathenaic Peplos for her to wear, and, on the other hand, we have seen her as the model warrior wearing her suit of armor. Such a complementarity, I will now argue, is accurately re-enacted in Iliad V 733–747. And the re-enactment, in terms of my present argumentation, is not only accurate but also artistic—so artistic, in fact, that it qualifies as a masterpiece. In what follows, I will analyze the artistry as well as the accuracy of this Homeric passage. And the artistry, as we are about to see, has produced here a Homeric masterpiece of metonymy.

3§13. Before I proceed, however, I need to highlight a heretofore missing piece in my analysis of the Athenian ritual of reweaving the Peplos of Athena every year for the occasion of celebrating her birthday at the festival of the Panathenaia. In the logic of that ritual, someone in the world of myth must have woven a peplos as a model, an absolute model, and it was this prototypical Peplos that was destined to be ritually rewoven forever, year after year, by the Athenians on each seasonally recurring occasion of the Panathenaia. In the logic of the charter ritual, that prototypical someone who wove the prototypical Peplos in the world of myth must surely have been the goddess Athena herself, and she must surely have woven the Peplos for herself to wear.

3§14. This logic, as I have called it, is an example of a theological way of thinking that is well known to researchers in comparative religion. On the basis of comparative studies centering on the interactions of myth and ritual in a wide variety of cultures, I can formulate in the following words such a theological construct: A divinity in the world of myth can be seen as the prototypical performer {140|141} of the rituals that mortals perform to worship that divinity. [11] This way, a divinity can be seen as a prototypical performer of worship or sacrifice or prayer, so that human performers of worship or sacrifice or prayer may follow the lead of the divinity, do as I do. [12] In terms of this formulation, then, the charter ritual of the Athenians in reweaving, year after year, the prototypical Peplos of Athena for her to wear all over again, year after year, is motivated by a prototypical act of weaving performed by the goddess herself in the world of myth.

3§15. That said, the missing piece in my analysis is now in place. The goddess Athena herself must have woven the prototypical Peplos that the Athenians rewove every year to worship her.

3§16. Such a prototypical Peplos, made by Athena in the world of myth, makes sense only if we keep in mind the historical context, which is the seasonal reweaving of the Peplos by the Athenians in the world of ritual. The setting for such a reweaving was the Panathenaia, that all-important festival celebrating not only the victory of Athena over the Giants but also the day of her birth—which as we have seen was the same sacred day as the day of her cosmic victory. And this prototypical act of weaving performed by Athena, just like the recurrent acts of weaving performed by the Athenians, would have included not only the pattern-weaving of the Peplos as a web but also the pattern-weaving of the story that was woven into that web.

3§17. In further analyzing the Athenian charter ritual of weaving a yearly Panathenaic Peplos for Athena, I have by now reconstructed a piece of the picture that was missing in my earlier analysis. That missing piece, as we have already seen, is the mythological detail about the weaving of the Peplos by the goddess Athena herself. And now we will see that this same piece fits perfectly into the overall picture that is being narrated in Iliad V 733–747, quoted in Extract 3-A. After the first mention of the peplos, at line 734, the wording at line 735 goes on to say that Athena herself had once upon a time woven this robe with her own hands. This peplos, woven by Athena in the world of myth, could be seen as the prototype of the Panathenaic Peplos, rewoven every year by the Athenians in their seasonally recurring world of ritual. The prototypical Peplos, as made by Athena herself in Iliad V 734–735, and the recurrent Peplos, as made by the Athenians for the Panathenaia, could be seen as one and the same sacred thing from the standpoint of the Athenians. Further, this prototype and all its recurrences were the same sacred thing not only in form but also in content. In other words, just as the pattern-weaving of each new Peplos for each new celebration of the Panathenaia was a seasonally recurring narration of the Gigantomachy, {141|142} so also the pattern-weaving of the prototypical Peplos made by the goddess Athena herself was a prototypical narration of the same Gigantomachy.

3§18. Here we encounter an internal contradiction that seems at first to be unfathomable. The myth that is retold here in Iliad V 734–735 about the prototypical pattern-weaving by and for Athena contradicts the world of time. The contradiction is built into the very core of the myth, which says explicitly that Athena wove the Peplos—while saying implicitly that she narrated the Gigantomachy by way of pattern-weaving the myth into the fabric. If this were so, of course, it should also be said that the Gigantomachy must have happened before the weaving—in the world of time. But the opposite could also be said: in the same world of time, the Gigantomachy must have happened after the weaving. That is because Athena was born fully-armed on the day of the Gigantomachy, and so the goddess could not have woven the Peplos before she was born.

3§19. Such contradictions in temporality, however, are neutralized by the myth. And that is because this myth is timeless. It operates on a principle of metonymical combinations that are sequenced in a timeless circle, not along a timeline. In this sequence, the Gigantomachy is followed by the weaving is followed by the Gigantomachy and so on, in an endless circle. In the circular timelessness of such a rewoven story, a poetic picturing of the Gigantomachy could be followed by a signal indicating that the ring-composition has come full circle, this is what happened in the Gigantomachy, followed by a signal that indicates a recircling, this is the story that Athena wove into her Peplos, followed again by this is what happened in the Gigantomachy, and so on.

3§20. But the Homeric reference to the Peplos made by Athena replaces such circularity with a linearity. From the standpoint of Athenians attending the quadrennial Panathenaic performances of Homeric poetry in the preclassical period and hearing the narration of Iliad V 733–747 about Athena and how she waged war against the Trojans, the sequence of events in this mythological narrative is linear, veering from the circular sequence of their charter myth about Athena and how she waged war against the Giants. And that is because Homeric poetry has replaced the circularity of timeless sequencing as we saw it at work in the myth of the Gigantomachy, substituting a linearity that follows a sequence controlled by time.

3§21. Here is how the substitution works in the narration of Iliad V 733–747. We see here a metonymic series of moments that combine with each other in a temporal sequence. But the first moment of this series of moments is not even mentioned in the narrative. That moment is when Athena is born wearing a suit of armor and getting ready to wage war on the Giants. Then, at that moment, after the war is won, Athena weaves her Peplos. And here is the first moment {142|143} that is actually noted in the metonymic series of moments narrated in Iliad V 733–747. After that, Athena puts on the Peplos and wears it. But this moment in the narration, when Athena actually puts on the Peplos, is not noted. After that, sometime after Athena puts on the Peplos, she takes it off and puts on her suit of armor as she gets ready to wage war on the Trojans. This later sequence of moments, as we have seen, is closely tracked in the narration of Iliad V 733–747.

3§22. So, in the linear logic of the timeline in this myth as retold in the narration of Iliad V 733–747—and as understood by the Athenians in the preclassical period and thereafter—the Gigantomachy happens before Athena’s weaving of the Gigantomachy into her Peplos. Then, since the weaving of the Peplos is a narration of the Gigantomachy, the goddess gets into her own story. But, once she is already inside her story, she can no longer wear the Peplos, since the story that is woven into her Peplos shows her wearing her armor, which is what she wore on that primal day when she was born and defeated the Giants. So, in the transition from the outer story, which is about the weaving, into the inner story, which is about the Gigantomachy, Athena takes off the Peplos she was wearing in the outer story and puts on the armor she will be wearing in the inner story told by way of weaving the Peplos.

3§23. Of course, those who heard the words of Iliad V 733–747 performed at the festival of the quadrennial Panathenaia in the preclassical and the classical eras of Athens would not get to hear the inner story of the Gigantomachy that was pattern-woven into the Panathenaic Peplos. That story, which Athena wove with her own hands, would have shown Athena at the timeless moment of her birth, fully armed and preparing to fight the Giants. That story would have visualized what had once been a timeless stop-motion picture of a fully-armed Athena stepping into her fiery chariot. Instead, after mentioning the Peplos that Athena has woven for herself to wear, Homeric poetry proceeds to show a woven picture in motion. The poetry now sets in motion what had once been that timeless stop-motion picture of a fully-armed Athena stepping into her fiery chariot. Unlike the metonymic sequence of the Gigantomachy that the goddess herself has woven into her Peplos, which circles back eternally, back to the re-weaving of the stop-motion picture, the motion picture of Homeric narrative moves the action forward in the linearity of time, so that the fiery chariot of the goddess will now move forward in time. So, in this motion picture, Athena will be attacking not the Giants in the Gigantomachy but the Trojans in the Trojan War that is being narrated by the Homeric Iliad. And that is because the metonymic sequence here is no longer circular. The sequencing has now become linear. And, in its new linearity, the metonymic sequence can now move forward in time. No longer does it have to circle back into the reweaving of the Gigantomachy. {143|144}

3§24. For Athena to join the Achaeans in their war against the Trojans in Iliad V 733–747, she must wear her armor. So, if we continue to follow the logic of the myth as retold here in the Iliad—and as understood by the Athenians—Athena must take off her Peplos—and then she must put on the armor that she wore once upon a time when she was born fully-armed from the head of Zeus.

3§25. The actual weaving of the Peplos, as a performance of a narrative, can be seen metonymically as the primordial act that arms the body of Athena in the newer myth about her joining the war against the Trojans, just as the older myth about her joining the war against the Giants—a war that is woven into the Peplos—arms her divine body from the very start.

3§26. To narrate the arming of Athena is to arm Athena. In other words, the narration about the arming is the same act as the arming itself. And, to take it further, the process of weaving the narration into the Peplos that Athena wears is the same thing as the process of arming Athena.

3§27. Viewed in this light, the transition that we see taking place in Homeric poetry from the moment when Athena weaves her Peplos to the moment when she arms herself is achieved by way of coordinating metonymy with metaphor. Here is what I mean. There is a sequence of metonymic combinations that drives the narration of Iliad V 733–747 from the moment when Athena weaves her Peplos to the moment when she puts it on, and from there to the moment when she takes it off, and from there to the moment when she puts on her armor. At the final moment of this metonymic sequence, there is a metaphoric substitution. A new moment, when the goddess puts on her armor to fight the Trojans in the Trojan War, is being substituted here for the old moment when she is already wearing this armor to fight the Giants in the Gigantomachy. And this substitution moves the action forward in the story of the Trojan War, thus preventing the arming scene from circling back to the reweaving of the story of the Gigantomachy.

3§28. In the circular timelessness of such a rewoven story, to repeat what I said before, a poetic picturing of the Gigantomachy could be followed by a signal indicating that the ring-composition has come full circle, this is what happened in the Gigantomachy, followed by a signal that indicates a recircling, this is the story that Athena wove into her Peplos, followed by this is what happened in the Gigantomachy, and so on. In this kind of endless circle, Athena would be seen weaving again and again the Peplos that she weaves for herself when she weaves the story of the Gigantomachy into her robe. But she does not have to wear this Peplos, since she is wearing the armor in the arming scene while she is telling the story of that arming scene. By contrast, in the linear timeline of the story as retold in the Homeric narrative of Iliad V 733–747, Athena must stop wearing the Peplos in order to start wearing the armor in her own story. And here is where we see that moment of nakedness between the moment when the {144|145} goddess slips out of her robe and the moment when she slips into the tunic that becomes the undergarment for the armor she will now wear in a new war. So, in the linear logic of Homeric narrative, the goddess must have already worn the Peplos that she once made when she pattern-wove her own story about the Gigantomachy, and it is this story that Homeric poetry now recombines by way of its own pattern-weaving. This recombining of the metonymic sequence by way of metaphorically substituting the Trojan War for the Gigantomachy is what leads here to the creation of a masterpiece of metonymy.

3§29. Such a coordination of metonymy with metaphor, achieved by way of recombination, brings me back to my initial formulation about masterpieces of metonymy in pattern-weaving. I will now repeat it here in the context of arriving at the core of my argumentation for Part Three:

A masterpiece of metonymy requires a kind of artistry that is not—and cannot be—restricted to metonymy. Instead, the artistry coordinates metonymy with metaphor.

3§30. To say it another way, a masterpiece of metonymy in pattern-weaving actually coordinates the process of making metonymic combinations on a horizontal axis, which is the primary process, with the secondary process of making metaphoric selections on a vertical axis. The actual coordination of a horizontal axis of combination and a vertical axis of selection is what produces the kind of variation that is so prized in the art of pattern-weaving. In terms of this medium of art, then, a masterpiece of metonymy is really a masterpiece of metonymy coordinated with metaphor.

3§31. In the luminous Homeric passage that we have just finished studying, Iliad V 733–747, we can see in action such a masterpiece of metonymy. And I now add the word perfect in describing this masterpiece, since the poetic virtuosity of Homeric poetry itself in picturing the robe of Athena is in its own turn pictured here as an absolutely perfect work of art, created by the divine hands of the immortal goddess herself, who is the all-powerful embodiment of Athens. Such absolute perfection is truly a perfect masterpiece.

A vision of Athena’s robe sculpted into the Parthenon Frieze

3§32. In my commentary on the text of Extract 2-U, where I quoted from the poem Ciris a lengthy description of Athena’s sacred robe, the Peplos, as it was paraded along the Sacred Way for all to see at the Panathenaic Procession, I briefly expressed a view about a folded robe that we see pictured in the relief {145|146} sculptures of Block 5 of the east side of the Parthenon Frieze. In my view, this robe is the same sacred Peplos of Athena. To back up this view, I start by showing what is being pictured. Here is a line drawing:

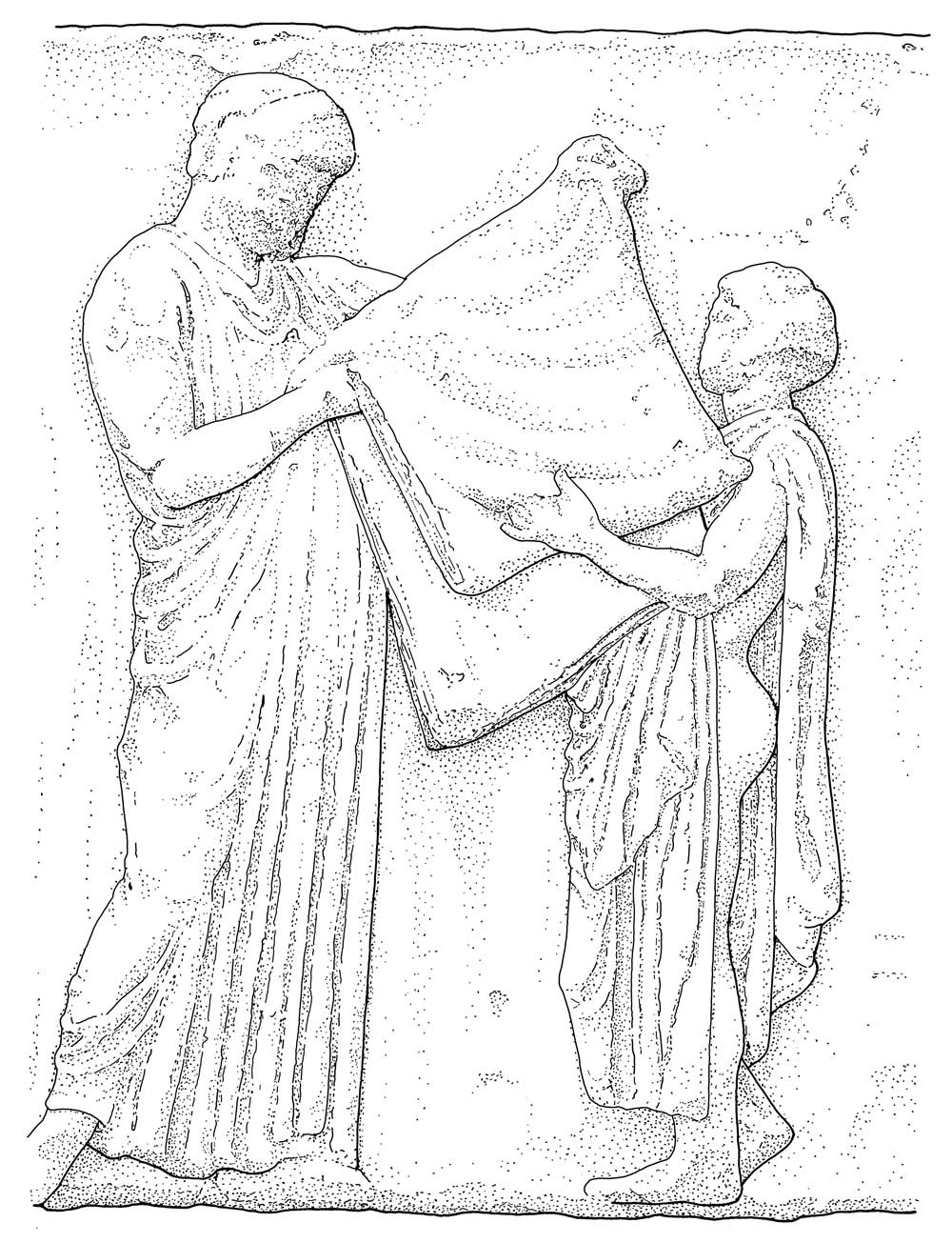

Extract 3-C

Relief sculpture: Folding of the Peplos of Athena. Block 5, east side of the Parthenon Frieze, Athens. Now in the British Museum. Drawing by Valerie Woelfel.

3§33. This relief sculpture is carved into a block (often called instead a “slab”) occupying the most prominent space of the Parthenon Frieze. This {146|147} block, “Block 5,” features a sculpted scene picturing five human figures in all. The two figures that I show in the line drawing are situated on the right side of Block 5, and there are also three other figures on the left side—to be described at a later point. Framing both sides of Block 5 are the sculpted figures of seated gods, larger in size than the five humans. On our left, in Block 4, the gods Zeus and Hera frame these humans, while in Block 6, on our right, the framing gods are Athena and Hephaistos. At a later point, I will have more to say about these larger-sized divine figures framing the five smaller-sized human figures.

3§34. One expert, Jennifer Neils, has aptly described the scene picturing the five human figures in Block 5 as “the high point” of the overall narrative of the Parthenon Frieze, “framed between the central columns of the temple façade,” [13] and “[i]t was here that the design [of the frieze] must have begun and for which an exceptionally long block [= Block 5] was ordered, quarried, and set into place.” [14] The expert whom I have just quoted about Block 5 goes on to describe the narrative sculpted into this “exceptionally long block” as “important enough to dictate the layout of the entire frieze” into “two processional files” that converge on this narrative. When she says “two processional files” in her description, she makes it clear that she has in mind the overall narrative of the Parthenon Frieze, which she sees as a representation of the Panathenaic Procession at the festival of the Panathenaia.

3§35. Earlier in my argumentation, I have already noted the importance of this procession as the setting for the ritual presentation of the Peplos. I will soon have more to say about the ritual presentation, as experts call it, but for now I concentrate on the Panathenaic Procession itself, as represented on the Parthenon Frieze.

3§36. In emphasizing the importance of the narrative carved into Block 5 at the east side of the Frieze, Neils is saying that the overall representation of the Panathenaic Procession converges on this one single narrative. In her wording, as we just saw, the Procession splits into “two processional files” proceeding eastward from the north and from the south sides of the Parthenon Frieze and then converging at the “high point” featuring the five human figures carved into Block 5 of the east side.

3§37. But the narrative of this “high point” is problematic, since experts have till now been unable to shape a consensus about what it all means. From the standpoint of a casual viewer’s first impression, the five human figures of Block 5 could understandably be described as “this unimpressive quintet.” [15] But I think that all five of these human figures are in fact all-important. {147|148}

3§38. To back up this line of thinking, I start by concentrating on the two human figures positioned on the right side of Block 5, as shown in the line drawing. These two figures are pictured here in the act of holding on to a fabric as they face one another, and I agree with those who think that the two of them are participating in a ritualized act [16] —an act that I have been describing up to now as the presentation of the Peplos. [17] In comments that I have published in the past about this “Peplos Scene,” however, I have consistently avoided asking myself this fundamental question: who is “presenting” the Peplos to whom? [18] In what follows, I will formulate an answer.

3§39. As we can see from the line drawing that I just showed, the figure on our left is a male adult, and the figure on our right is an adolescent, shorter than the corresponding adult by well over a head’s length. The gender of the adolescent is no longer clearly distinguishable, partly because the surface of the relief sculpture has been so massively eroded. While I agree, as I said a minute ago, with those who think that this scene, as sculpted into Block 5 of the east side of the Parthenon Frieze, is picturing some kind of ritual presentation involving a peplos, I also agree with Joan Connelly’s interpretation of the male figure as the prototypical Athenian king Erekhtheus and of the adolescent figure as the king’s youngest daughter. [19] Here we come to a point of controversy, since some experts do not accept Connelly’s interpretation—even if there is general agreement about what we see being depicted in this scene, which is, some kind of a ritualized presentation. [20] In my case, I do accept Connelly’s argument for identifying the figures in question as Erekhtheus and his youngest daughter, and I will now explain why.

3§40. In terms of Connelly’s argumentation, the stop-motion picture of the narrative we see recorded here in the relief sculpture corresponds to a climactic moment that takes place in a charter myth of the Athenians. Traces of this charter myth have been preserved primarily in the fragmentary tragedy Erekhtheus, composed by Euripides and initially staged sometime in the late fifth century BCE, as also in a scattering of other ancient sources. The myth, which is evidently older than the tragedy derived from it, told about the victory of the people of Athens, led by their king, Erekhtheus, over an invading horde of Thracians led by the king of Eleusis, Eumolpos, in a war that almost resulted in {148|149} the capture of Athens. [21] The historian Thucydides (2.15.2) makes an overt reference to the myth, treating it as if the war between Erekhtheus and Eumolpos had really taken place in prehistoric times.

3§41. This particular charter myth about Erekhtheus, even if it is older than the tragedy named after this hero, may not have been as old as another charter myth we have already considered, which centered on the victory of the goddess Athena and the other Olympians over the Giants, but it was still old enough to be integrated into the overall mythological narrative conveyed by the vast array of sculpted images built into the Parthenon—specifically, into the continuum of relief sculptures that we know today as the Parthenon Frieze. Angelos Chaniotis has argued most effectively for the historical reality of such an integration of this charter myth into the Parthenon Frieze. [22]

3§42. According to the myth, it had been divinely ordained that Eumolpos and his horde would succeed in capturing the city of Athens and its inhabitants unless the Athenian king Erekhtheus slaughtered a daughter of his as the virginal victim of a human sacrifice. One of the daughters responded to the crisis by volunteering to serve as the victim, and so she was the first to die, though in the end two other daughters also gave up their lives. In Apollodorus Library 3.15.4, it is said that Erekhtheus slaughtered the youngest daughter first, and that the older daughters responded to this death by killing themselves in their own turn. [23] In the wording of the drama Erekhtheus, it is clear that there were three virginal daughters in all, zeugos triparthenon ‘the yoking of three virgins’ (Euripides F 47.1 ed. Austin). [24] In the Athenian charter myth about this set of three daughters, as we know from ancient lexicographical sources, no names were given to the girls, and, in line with sacred protocol, the Athenians referred to them simply as the Parthénoi or ‘Virgins’:

Extract 3-D

Parthénoi: this is how they [= the Athenians] called the daughters of Erekhtheus, and this is how they worshipped them [= gave them tīmē ‘honor’]. [25]

Hesychius s.v. Παρθένοι [26] {149|150}

3§43. There is a parallel pattern in a Theban myth, as reported by Pausanias (9.17.1), about two female heroes named Androkleia and Alkis, who killed themselves as ritual substitutes for their father Antipoinos, whose death, as ordained by an oracle, was a precondition for making his people victorious over the people of Orkhomenos (the name Anti-poinos means, aptly, ‘the one who is connected with a substitute ransom’): in compensation for their self-sacrifice, the bodies of the girls were buried within the sacred precinct of Artemis Eukleia, where they received tīmai ‘honors’ from their worshippers. [27]

3§44. There is yet a parallel pattern in an Athenian myth about a female hero called Makaríā, virgin daughter of Herakles who willingly offered herself as a human sacrifice to save Athens and her own siblings. The myth about these children of Herakles, taking refuge in Athens after fleeing from their persecutor, Eurystheus, is attested in a drama by Euripides, The Sons of Herakles, featuring explicit references to the sacrifice of the virgin sister, daughter of Herakles (especially at lines 502, 550–551, 558–562, 574–596). The euphemistic title of the virgin, Makaríā, meaning ‘the Holy One’, is not even spoken in this drama as we have it: instead, she is simply the parthénos (as at lines 489, 535, 567, 592), and we know of her title Makaríā only from the testimony of later sources. [28]

3§45. That said, I return to the myth about the Parthénos who was the daughter of Erekhtheus. In terms of Connelly’s interpretation, the moment that is sculpted into Block 5 of the east side of the Parthenon Frieze shows Erekhtheus in the act of preparing for the sacrificial slaughter of this Parthénos, and that is why he is dressed as a priest, wearing an ankle-length short-sleeved beltless khitōn or tunic. [29] At this precise moment of preparation, according to Connelly, the father is handing over to his virginal daughter a peplos.

3§46. In terms of my own interpretation, the Parthénos herself would have originally woven the peplos, and, after the original weaving, this precious heirloom would have been stored in her father’s residence until the daughter was ready to wear it as her wedding gown. But now—here I return to my tracking of Connelly’s interpretation—the father is handing over the peplos to the Parthénos in preparation for a different occasion. The Parthénos will now be wearing this peplos not for her wedding but instead for her ritual slaughter as a willing virginal sacrifice.

3§47. As Connelly observes, there are myths about virginal sacrifices that actually show the victim wearing a peplos for the occasion of her ritual slaughter. [30] A shining example is the virgin heroine known euphemistically as Makariā. {150|151} I have already noted the references to this parthénos, this virgin daughter of Herakles, in the drama by Euripides, The Sons of Herakles. In the wording of this drama, the doomed girl herself declares that her sacrificer must cover her, at the moment of the sacrificial slaughter, within the folds of a peplos, as we see at line 561 (πέπλοις). Another example is the heroine Iphigeneia, as we see from wording that refers to her virginal sacrifice in the Agamemnon of Aeschylus: at line 233, it is said explicitly that Iphigeneia is covered within the folds of a peplos at the moment when she is ritually slaughtered (πέπλοισι). [31] In both these two contexts, the use of the plural form of the word, peploi, is apt. As we saw earlier in Extract 2-U (Ciris 30), which shows another context involving a plural form of peplos (Latin pepla), the basic idea of ‘foldings’ is actually built into the meaning of this word. This emphasis on the multiple folds of the peplos leads me to think that my use of the word wear is not suitable for describing the function of the peplos: as we will see later, the word wrap is a better fit.

3§48. I must add, in the case of Iphigeneia, that this virginal heroine is a surrogate of the virginal goddess Artemis. Surveying the traditional myths and rituals connected with Iphigeneia, I have found a version of the myth, as retold in the epic Cycle (plot-summary by Proclus of the Cypria by Stasinus p. 104 lines 12–30), where the goddess Artemis miraculously substitutes a deer for Iphigeneia at the sacrificial altar, and this substitution takes place at the exact moment when Iphigeneia is about to be slaughtered (lines 19–20). So, in this version of the myth, a deer is killed instead of Iphigeneia, and, in the meantime, Artemis transports the girl to a remote place named Tauris, where Iphigeneia is immortalized as a theos or ‘goddess’ in her own right (lines 18–19). So, the virgin Iphigeneia as the mortal surrogate of Artemis is transformed into the goddess Artemis herself, who can now be seen in her own specialized role as an immortal virgin.

3§49. In the myth as retold in the Agamemnon of Aeschylus, by contrast, this salvation of Iphigeneia is not made explicit, and her story stops when she dies—not when she is rescued from death and becomes the goddess Artemis in her divine role as an immortal virgin.

3§50. It is relevant here, as I have argued in another project, that the drama of Aeschylus highlights the anger vicariously felt by Artemis on behalf of her surrogate—anger against Agamemnon and Menelaos for their willingness to sacrifice Iphigeneia. Artemis is angry at them even though it was she who ordained the sacrifice of her own surrogate as a precondition for her releasing the winds that blew eastward and made it possible for the Achaeans to sail off to Troy. [32] In the epic Cycle as well, the anger of Artemis is highlighted, and the {151|152} word for this anger is mēnis (Cypria p. 104 lines 14, 16); in that context, the word refers to the anger of the goddess at Agamemnon for boasting that he is a better hunter after he shoots down a deer. It is no coincidence that the sacrificial substitute for Iphigeneia is likewise a deer, as we just saw (Cypria p. 104 lines 19–20). [33]

3§51. Similarly, I will now argue that the virginal heroine known simply as the Parthénos is a surrogate of the virginal goddess Athena in the myths and rituals pictured on the Parthenon Frieze.

3§52. Here I return to my starting point concerning the scene that we see sculpted into Block 5 on the east side of the Parthenon Frieze. In terms of my interpretation, as I noted from the start, this scene refers to the moment when the presentation of the Peplos is performed at the Panathenaia. But now I need to make a distinction between the Peplos that was seasonally rewoven in the world of ritual and the peplos that was originally woven in the world of myth. In the world of ritual, as we saw many times already, the Peplos was seasonally rewoven by the Athenians and presented by them to the goddess Athena on the occasion of the Panathenaic Procession, which took place at the seasonally recurring festival of the Panathenaia. In the world of myth, on the other hand, there was a peplos originally woven by the Parthénos or ‘Virgin’, and this peplos was later presented to her by her own father—for her to wear in preparation for her ritual slaughter on the occasion of the original Panathenaic Procession, which was the climax of the original festival of the Panathenaia.

3§53. But I stop myself when I say wear here. As in the case of other virginal sacrifices that we have already noted, the word wrap would be a better fit. I will now explain why.

3§54. The multiple folds that are featured in the sculpted representation of the peplos indicate a fabric of relatively huge proportions, evoking the image of the gigantic peplos that used to be presented to the goddess herself at the climax of the Panathenaic Procession. The gigantic proportions of the peplos in the ritual of this procession seem at first ill suited for the small girl in the myth as represented in the sculpted image. Seen through the bifocal lenses of myth and ritual combined, however, the image is smoothed out: the sacrificial death of the mortal little girl in the myth points to her role as the sacred surrogate of the biggest of all girls, the immortal Parthénos, in the ritual of the Panathenaic Procession.

3§55. I will have more to say in a minute about the corresponding myth of an original Panathenaic Procession, which supposedly took place at an original festival of the Panathenaia. For now, however, I will simply continue to focus on the idea that the little mortal Parthénos, in weaving her peplos, is a surrogate {152|153} of the great immortal Parthénos, the goddess Athena herself. And this idea is correlated with the further idea that Erekhtheus, figured as both king and chief priest of the Athenians, is a surrogate of Zeus himself.

3§56. To back up these two correlated ideas, I return to lines 734 and 736 of Iliad V, quoted in Extract 3-A. At line 734, we saw the goddess Athena in a primal moment, when she takes off the peplos that she had woven for herself with her own hands, and, at line 736, we saw her in another primal moment that happens seconds later, when she puts on a khitōn or ‘tunic’ as an undergarment for the armor she will wear in war. When I analyzed these two lines, I highlighted a third primal moment that comes between the two moments when the goddess slips out of the peplos and when she slips into the khitōn. In this intervening moment, I noted, the goddess must be in the nude. Now I highlight two details that I have not yet noted in these same two lines.

- At the moment in line 734 when the goddess takes off her peplos, it is said that she does so ‘at the threshold of her father’.

- At the following moment in line 736 when she puts on the khitōn, it is said that this tunic actually belongs to her divine father.

3§57. In the myth of the Gigantomachy, as viewed in the temporal linearity of Homeric poetry, it would have been this same khitōn that the goddess was already wearing underneath her armor when she was born fully formed and fully armed from the head of Zeus. That is why Homeric poetry can refer to this khitōn as belonging not to the goddess but instead to her divine father. As for the peplos that Athena leaves ‘at the threshold of her father’, it now appears that this peplos too belongs to the divine father, to be left behind in his residence, as if Zeus were the father of a future bride.

3§58. I see comparable details in the relief sculpture of Block 5. Here too, the Parthénos is about to leave the residence of her father. And, although she is about to put on her peplos instead of taking it off, she is seen in an intervening moment of changing her dress, just as the goddess Athena is changing her dress in Iliad V 734–735. In this intervening moment, as sculpted into Block 5 at the east side of the Parthenon Frieze, the Parthénos is practically in the nude. Connelly gives a lively description:

She is about to be sacrificed at the hand of her father, who is dressed as a priest for the event. […] The girl’s dress is, very conspicuously, opened at the side, revealing her nude buttocks. It would be unthinkable for a historical girl, an arrhēphoros from an elite family, to be portrayed with backside casually exposed during the most sacred moment of the Panathenaic ritual. […] I would argue that the girl’s nudity is not {153|154} accidental. Her garment is open to communicate that she is in the process of changing clothes. [34]

3§59. I agree with Connelly’s argument that this scene, as represented in the relief sculptures of the Parthenon Frieze, is happening not in the world of ritual as current in Athens at the time of the building of the Parthenon in the middle of the fifth century BCE. [35] Granted, in terms of the ritual world as it existed in that historical period, we might expect elite girls known as the Arrhēphoroi to be the chosen handlers of the Peplos. But the scene sculpted into Block 5 of the east side of the Parthenon Frieze is happening not in the historical world of Athenian ritual but in the prehistorical world of a charter myth telling about the time when Eumolpos and his horde of Thracians were attacking Erekhtheus and his fellow Athenians.

3§60. So, in terms of Connelly’s argument, the peplos that is pictured in this scene was woven not by the young girls known as the Arrhēphoroi in the world of Athenian ritual in historical times. Instead, the weaving of the peplos as shown in Block 5 happened in the world of Athenian myth, and the weaver was a virgin known simply as the Parthénos, the Virgin. After the Parthénos wove her peplos, this most precious heirloom would have been stored in the residence of her father until it was time for her to become a bride, ready to be given away in marriage. At the time of the wedding, the father would have handed over to the Parthénos this peplos that she herself had pattern-woven with her own hands while residing in her father’s residence. Then, taking this peplos off her father’s hands, the Parthénos would now slip into it and wear it for her wedding. [36] But, tragically, the presentation of the peplos in this special case would be followed not by a wedding. Instead, what awaits the Parthénos is an act of ritual slaughter. So, the peplos that she receives in this scene of presentation is not exactly the kind of pretty dress that is made ready for a pretty girl to wear, tailor-made, fitting perfectly the contours of her beautiful body. She would not be wearing a peplos that fits her that way. Rather, she would be wrapped into the many folds of the massive peplos that we see represented in the sculpture.

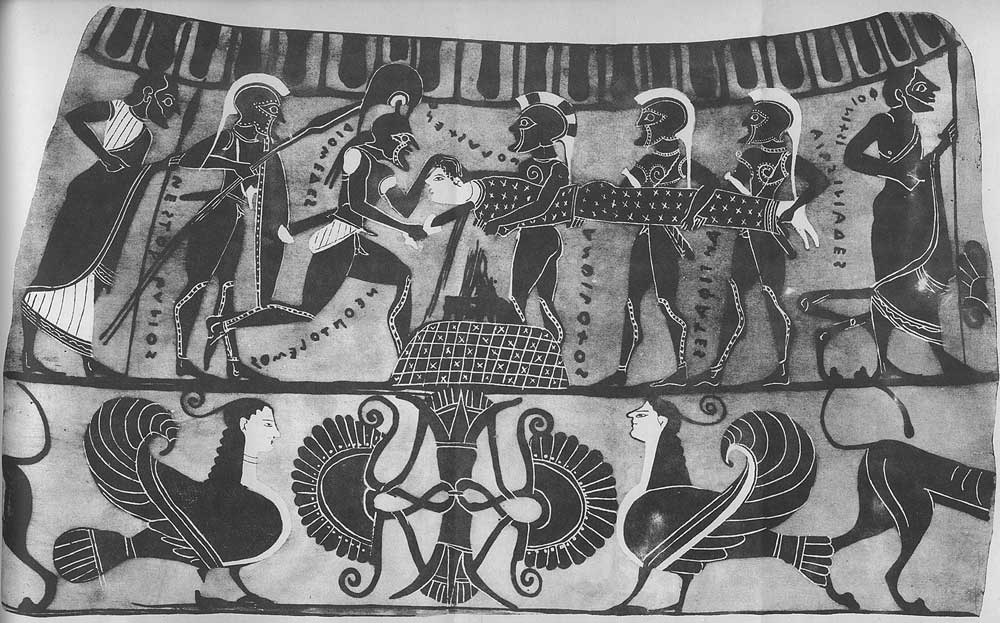

3§61. For a parallel, I cite the picturing of the Trojan princess Polyxena in a vase painting that shows how the Achaeans slaughter this virgin after they capture Troy, sacrificing her at the tomb of Achilles. The picture captures {154|155} the moment when the girl’s throat is slit and her blood gushes forth, pouring down upon a sacrificial altar positioned on top of the hero’s tomb. And, at that moment of sacrificial slaughter, the girl is all wrapped up inside the folds of a massive peplos. Here is the picture:

Extract 3-E

London, British Museum. Tyrrhenian amphora, Attic Black Figure. Date: ca. 570–560 BCE. Side A: sacrifice of Polyxena. Primary citation: ABV, 97.27; Para. 37. Beazley number 310027. Line drawing from Plate XV in Walters 1898.

3§62. Using the comparative evidence of this picture, Connelly reasons that the peplos presented by the father to the Parthénos in the scene of presentation sculpted into the Parthenon Frieze could be seen as a shroud. [37] As I have been arguing here, however, this peplos could just as easily be seen as a wedding dress—even if the many folds of this massive fabric will cover the girl’s body not for a wedding but for a human sacrifice.

3§63. The Parthénos, as she leaves the residence of her priestly father, could be getting dressed in her peplos as a bride who is getting married to a bridegroom. In a sense, the father is giving away the bride. But the destiny of this virgin is not to be married off but rather to be killed off. And, just as the bride is for the father to give away, the peplos that the Parthénos had woven is now for him to give to her to wear as she prepares to leave his residence. There is a comparable situation in {155|156} Iliad V 734–735, where Athena is pictured as leaving the residence of her father when she slips out of her peplos and slips into the khitōn that she wears as an undergarment for her suit of armor. In this case, however, the change of clothes is in reverse: she is slipping out of the peplos and slipping into the khitōn.

3§64. Viewing the scene sculpted into Block 5 on the east side of the Parthenon Frieze as a ritual where the father is giving away the bride, I find it most useful to paraphrase the anthropological perspective of James Redfield in analyzing the myths and rituals concerning the Locrian Maidens. [38] The basic details of these myths and rituals, originating from a variety of populations who described themselves as Locrians, are attested primarily in Lycophron’s Alexandra (1141–1173) together with the accompanying scholia, where we see that the idea of killing the Locrian Maidens on the level of myth is correlated with the idea of marrying them off on the level of ritual. According to one particular Locrian tradition, reported by Polybius (12.5.7), only those girls who were descended from the most prestigious families of Locris, known as the Hundred Houses, were eligible for participating in the ritual of surrogacy that re-enacted the experiences of the prototypical Locrian Maidens. [39] Redfield has this to say about the sacrifice experienced by the Locrian Maidens in myth as correlated with ritual:

Only in the mythical version of the ritual were they [= the Locrian Maidens] actually sacrificed; in the actual version they went through an experience of sacrifice [emphasis mine] and came out the other side enriched. The two versions, in fact, represent the doubleness of the Greek wedding, as transfer (by and for males) and as transformation (of and for women), as sacrifice and initiation. [40]

3§65. So, to sum it all up, my interpretation of the scene that is sculpted into Block 5 on the east side of the Parthenon Frieze supports the central theory of Connelly, who argues that this scene features Erekhtheus in the act of preparing his virginal daughter—known to Athenians simply as the Parthénos—for a human sacrifice. I find it apt to quote here the anthropological perspective of Redfield on ancient Greek wedding rituals in general: he speaks of “the wedding as the father’s sacrifice of his daughter, and as requiring the bride’s consent.” [41] {156|157}

A prototypical Panathenaic Procession

3§66. So far, I have focused on one single scene that is pictured in the relief sculptures of the Parthenon Frieze. And I have interpreted this scene, sculpted into Block 5 on the east side of the Parthenon Frieze, as the climactic moment of a charter myth that centers on a prototypical presentation of a prototypical peplos to the Parthénos, the virgin daughter of Erekhtheus. But now I propose to consider the Frieze in its entirety, ready to embrace the idea that the visual narrative of the Frieze is picturing a prototype of the entire ritual that is aetiologized by the charter myth. And this ritual is the Panathenaic Procession. The idea, then, is that the Parthenon Frieze, considered in its entirety, pictures a prototypical Panathenaic Procession.

3§67. I start by quoting Joan Connelly’s description of the Parthenon Frieze as it fits into the overall structure of the Parthenon:

[It is] a band of sculptured relief showing 378 human and 245 animal figures and running some 160 meters (525 feet) around the top of the cella wall within the colonnade. Set at a height of 14 meters, or about 46 feet, and deeply shaded under the ceiling of the peristyle for most of the day, the frieze measures just over 1 meter from top to bottom, or roughly 3 feet 4 inches in height. […] Truth be told, the frieze would have been difficult to see from ground level. The earth-bound Athenian would, of course, have made out the profiles of figures set against the frieze’s deep blue painted background. Skin pigments of reddish brown for men and white for women would have made the sexes distinguishable at a distance. […] But viewers would have already known the subject matter, thus easily recognizing the figures glimpsed between the columns. Still, to peer straight up at the frieze from thirty to forty feet below would have required an inordinate amount of squinting and neck craning. [42]

3§68. I agree with Connelly when she concludes:

In fact, the primary intended viewers of the Parthenon frieze were not mortal visitors to the Acropolis but the gods eternally gazing down upon it. [43]

3§69. So, in terms of this argument, we can say that the story of the Parthenon Frieze, presented here as an ultimate spectacle for the divine gaze, is the story of the Panathenaic Procession. But the story depicts not the current {157|158} version of the procession, as it took place at the seasonally recurring festival of the Panathenaia in the era when the Parthenon was built. Rather, the story depicts the supposedly original version. That is what Connelly argues, and what I argue as well.

3§70. In order to grasp the narrative logic of the Parthenon Frieze in picturing this supposedly original procession, I start again with that singular picture that has been the focus of attention up to now. In that picture, replicated in the line drawing that I showed when I started my analysis, we see the climactic moment when Erekhtheus is presenting to the Parthénos the peplos that this virginal girl had once woven—and that she will now be wearing for her virginal sacrifice.

3§71. That picture, as I indicated from the start, is situated on the right side of Block 5 on the east side of the Parthenon Frieze. Zooming out from that picture, we now see on the left side of Block 5 three other human figures. Moving our view from right to left, we start with the first of these three figures. She is a grown woman, to be identified with Praxithea, the wife of Erekhtheus, and we know her name from a variety of ancient sources (including Lycurgus Against Leokrates 99). [44] Moving further to the left, we see sculpted into the same Block 5 the other two Parthénoi who will be killed in the virginal sacrifice. They are taller than the Parthénos who is receiving the peplos on the right side of Block 5, and this detail on the corresponding left side matches those versions of the myth that describe the sacrificed virgin as the youngest of the three daughters of Erekhtheus. Moving our view further to our left, we see sculpted into Block 4 of the east side of the Parthenon Frieze two seated figures, larger in size than the five human figures representing the holy family of Erekhtheus and Praxithea and their three daughters. These two larger figures are the gods Zeus and Hera. Symmetrically, in Block 6 all the way across to our right, we see two other seated figures, again larger in size than the human figures, and these larger figures are the gods Athena and Hephaistos.

3§72. Having by now seen four of the twelve Olympian gods, we are ready to look at the other eight. Zooming further out, we get to see these gods as well. Their outer positioning frames the inner positions of Zeus and Hera on our left and of Athena and Hephaistos on our right—while the inner positioning of these four Olympian gods frames the innermost positions of the Parthénos and Erekhtheus and Praxithea and the two other Parthénoi. [45] {158|159}

3§73. And, zooming still further out, we see figures of humans and sacrificial animals processing toward the assembly of gods from the other three sides of the Frieze. These figures, Connelly argues, are processing in a prototypical Panathenaic Procession, which marks the victory of the Athenians in their battle against the invading horde led by Eumolpos:

This procession brings animal offerings for the post-battle, thanksgiving sacrifice that follows the Athenian victory. The Parthenon frieze can thus be understood to show not just some historical Panathenaia but the very first Panathenaia, the foundational sacrifice upon which Acropolis ritual was based ever after. The offerings of cattle and sheep, of honey and water, as shown on the north and south friezes, are all made in honor of the king and his daughters as described in Euripides’s Erekhtheus. The cavalcade of horsemen is the king’s returning army, back from the war just in time to join the procession celebrating their victory. [46]

3§74. Such a picturing of a prototypical Panathenaic Procession seems to include details that go beyond the context of a formal procession—as we would expect such a procession to occur in the historical era of the Panathenaia. For example, in the formulation I have just quoted from Connelly, the cavalcade could be seen as part of the military action in the charter myth about the war waged by the Athenians against Eumolpos and his Thracians—not only as part of the procession itself. I would add that the picturing of men riding on horses in the relief sculptures of the Frieze could also be referring to aspects of the overall festival of the Panathenaia, which featured athletic competitions in equestrian events. [47] And the picturing of such equestrian competitions in the Parthenon Frieze could merge with the picturing of a parade of participants in these competitions. This way, the equestrian competitions could be seen as part of the Panathenaic Procession. In other words, the procession could include metonymically the athletic competitions that culminated in the procession.

3§75. Most experts think that the equestrian scenes of the Parthenon Frieze are in fact representations of horse-riders parading in the Panathenaic Procession. [48] I argue, however, for a combined perspective. In terms of my argument, the cavalcade pictured on the Frieze could be seen as a set of events that are simultaneously processional and athletic. And the athletic events, from the {159|160} standpoint of the corresponding charter myth, could be re-enacting wartime events that happened in the mythologized age of heroes.

3§76. A related set of events that we see pictured in the relief sculptures of the Frieze involves charioteering. There are twenty-one chariot teams represented on the Frieze, with eleven chariots featured on the north side and ten on the south side; in each case, the chariot is shown with four horses, a driver, and an armed rider, who is wearing a helmet and a shield. [49] In the case of the armed rider, as we know from a variety of ancient sources, the word for such a figure standing on a chariot was apobatēs, which means literally ‘he who steps off’. [50] The Parthenon Frieze shows these armed riders in a variety of maneuvers directly involved with the chariots in which they are riding: the riders are shown stepping into the chariot, riding in the chariot, stepping out of the chariot, and running alongside the chariot; in two cases, the apobatai are evidently wearing a full set of armor. [51]

3§77. In another project, I have studied at length the bits and pieces of surviving evidence about a most prestigious athletic event, held at the festival of the Panathenaia, involving a competition in apobatic charioteering. [52] In that project, I already argued that the chariot scenes of the Parthenon Frieze are picturing not only a parade of participants competing in the apobatic chariot races held at the festival of the Panathenaia. More than that, much more, these same scenes are simultaneously picturing some of the greatest imaginable moments that could ever be experienced in the course of actually competing in these apobatic chariot races. In addition, just as the cavalcade that is pictured on the Frieze could refer to the mythological war waged by the Athenians against Eumolpos and his horde of Thracians, so also the chariot scenes could refer in part to that same war. In other words, the stop-motion picturing of apobatic chariot scenes in the Parthenon Frieze captures not only moments of participation in the Panathenaic Procession but also moments of actual engagement in apobatic chariot racing—and even in the warfare of chariot fighting. That kind of warfare, of course, would be happening in a heroic era, not in the era when the Parthenon was built.

3§78. So, as in the case of the cavalcade that is pictured on the Frieze, the chariot scenes could be seen as referring to events that are simultaneously processional and athletic. And the formulation that I applied in the case of the {160|161} cavalcade can apply here as well: the athletic events of apobatic charioteering, from the standpoint of the corresponding charter myth, could be re-enacting wartime events that happened in the mythologized era of heroes.

3§79. I highlight here a contrast between the perspectives of ritual and myth in Athenian traditions. In the world of ritual, the Panathenaic Procession is followed by the presentation of the Peplos at the seasonally recurring festival of the Panathenaia. In the world of myth, by contrast, we cannot say that the procession happens before or after the presentation of the peplos. We see here once again a theological way of thinking about prototypical events, comparable to what we saw earlier when we considered the metonymic sequence of the myth about the Gigantomachy, which is followed by the narrating of the Gigantomachy by way of weaving the narration into the Peplos woven by Athena: in that case, the Gigantomachy is followed by the weaving is followed by the Gigantomachy and so on, in an endless circle. So also in the myth about the presentation of a peplos to be worn by the Parthénos, we can say that the original presentation is followed by the original Panathenaic Procession is followed by the presentation and so on, in an endless circle. Such is the logic of the prototypical Panathenaic Procession.

The defining moment in the Panathenaic Procession

3§80. Before I proceed, I stop here to take a closer look at the defining moment of the Panathenaic Procession as sculpted into the Parthenon Frieze—the moment that I have been describing as the presentation of the Peplos. In the book Homer the Classic, I had this to say about the Panathenaic Frieze as the defining context of that all-important moment:

The ritual drama of the Panathenaic Procession, as represented on the Parthenon Frieze, is central to the whole Panathenaic Festival, central to Athena, central to Athens. It is an ultimate exercise in Athenian self-definition, an ultimate point of contact between myth and ritual. The dialectic of such a Classical Moment has us under its spell even to this day. And it is precisely the anxiety of contemplating such a spellbinding moment that calls for the remedy of objective observation, from diachronic as well as synchronic points of view. [53]

3§81. In using the terms synchronic and diachronic in this formulation, I was following a linguistic distinction made by Ferdinand de Saussure. [54] For Saussure, {161|162} synchrony and diachrony designate respectively a current state of a language and a phase in its evolution. [55] Applying this terminology to the language, as it were, of the Parthenon Frieze, I was arguing that the visual narrative of the Frieze show shifts in meaning—once we view it not only synchronically but also diachronically.

3§82. That said, I focus here again on that Classical Moment. This is the moment, as I just said, when the Peplos is presented. But whose peplos is it? From a diachronic point of view, as we will now see, it is the Peplos of Athena, and that is why I just formatted the word as “the Peplos,” not “a peplos.” From a synchronic point of view, however, the referent here is not the Peplos of the goddess Athena but a peplos woven by a heroine known simply as the Parthénos or ‘Virgin’, who is the youngest daughter of the hero Erekhtheus, king and high priest of Athens. This moment, as I just narrated it, is a reconstruction, painstakingly put together on the basis of synchronic analysis. From this synchronic point of view, then, Erekhtheus and the Parthénos are father and daughter. From a diachronic point of view, however, the relationship is different—and far more complex.

Diachronic Athena

3§83. As Douglas Frame has argued at length—and most persuasively so—a prehistoric phase of Athenian mythmaking pictured the hero Erekhtheus as both the son and the consort of Athena herself, who was formerly not a divine virgin but a mother goddess, and who became an exclusively virgin goddess only in the era of Solon, around 600 BCE. [56] At a later point, we will consider a further argument, that an older form of the goddess Athena was formerly both a virgin and a mother, like the goddess Hera, recycling from mother to virgin to mother in an endless cycle. For now, however, I simply offer a working formulation about the theological essence of the goddess Athena as she was worshipped by the Athenians in the classical era when the Parthenon Frieze was created. My formulation is shaped by a diachronic point of view that links the goddess Athena, as a former mother, to the mortal Parthénos as a permanent virgin. From this point of view, the Parthénos who died a virgin is the daughter that Athena never had, making it possible for Athena to become an immortal virgin who forever replaces her mortal surrogate. Similarly, as I have already argued, Artemis is the immortal virgin who forever replaces her own mortal surrogate, who is Iphigeneia in some versions of the myth. {162|163}

Back to the defining moment in the Panathenaic Procession

3§84. I return to the moment when the Peplos is presented in the scene sculpted into Block 5 on the east side of the Parthenon Frieze. By now we see that the recipient of this presentation is really the goddess Athena from a diachronic point of view, though she seems to be the mortal Parthénos from a purely synchronic point of view. Either way, what strikes the eye at this defining moment is the artistry of the sculpture in representing the Peplos itself, with its folds and its selvedge still clearly visible despite the massive erosion in the stonework. [57] The sculpting of this Peplos, I will now argue, is a shining example of a special kind of metonym—what we have been calling a synecdoche—for the sculpting of the Panathenaic Frieze in its entirety.

3§85. In making this argument, I find it relevant here to repeat the term story-frieze, as we saw it used before with reference to the narrative technique of pattern-weaving in the process of narrating myths, including the myth of the Gigantomachy as woven into the Peplos presented to Athena at the festival of the Panathenaia. [58] This term story-frieze, as a metaphor, is good to think with, provided we keep in mind that the creation of notional “friezes” in weaving cannot be derived from the creation of real friezes in sculpting. The direction of derivation was actually the reverse, as we can see from the fact that the pattern-weaving of stories like the myth of the Gigantomachy was an old tradition going back to prehistoric times, whereas the sculpting of a continuous narrative sequence like the Parthenon Frieze was an innovation of the classical period, concurrent with the time when the Parthenon was built. That said, I stress the intuitive appeal of comparing the artistry of sculpting a story into a frieze with the artistry of pattern-weaving a story into a fabric.

3§86. Returning to the argument, then, I find it relevant to apply this term story-frieze in the context of the Parthenon Frieze, since the artistry of this frieze exemplifies a cross-over from the craft of weaving to the craft of sculpture. And a signature of this cross-over, I argue, is the sculpting of the Peplos of Athena at the defining moment of its presentation to the goddess. In other words, the sculpting of the Peplos—and, by extension, the sculpting of the Panathenaic Procession in its entirety—is inspired by the pattern-weaving of the Peplos of Athena. [59] {163|164}

Linking the robe of Athena to her bronze shield in the interior of the Parthenon

3§87. The cross-over extends further. [60] The artistry of the craft of pattern-weaving crosses over also into the craft of metalworking. A prime example is a masterpiece of metalwork that was once housed in the interior of the Parthenon, abode of the statue of Athena Parthénos, made by Pheidias. Positioned next to this colossal gold-and-ivory statue of Athena Parthénos was the colossal bronze shield of the goddess, likewise made by Pheidias—and this sacred shield showed a complex metalworked narrative on its concave interior as also on its convex exterior. [61]

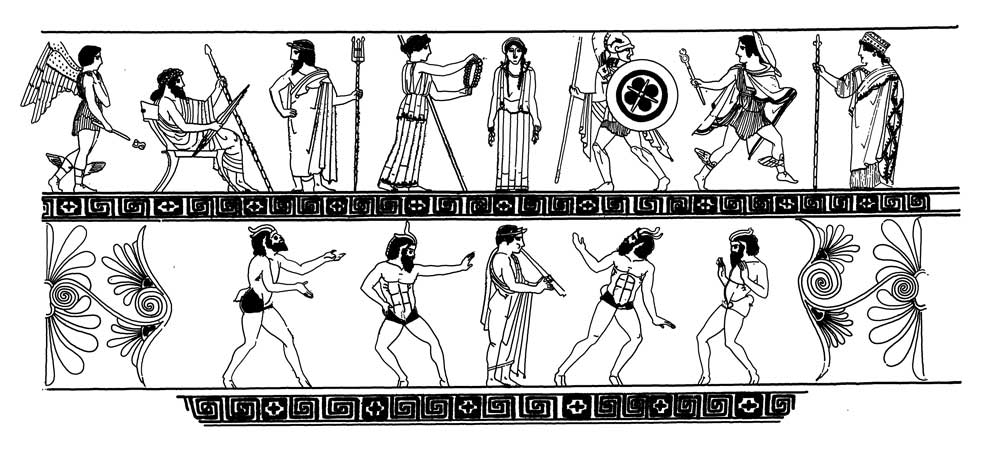

3§88. We find the essential facts about this bronze shield of Athena in a description by Pliny the Elder, which I am about to quote. As we will see, the convex exterior of the Shield featured a metalworked narrative of the Amazonomachy (Amazonomakhiā), that is, the primal conflict between the Athenians and the Amazons (Amazones); as for the concave interior, it featured a likewise metalworked narrative of a corresponding primal conflict. In this case, the narrative was none other than the Gigantomachy (Gigantomakhiā), that primal conflict between the gods and the giants (gigantes). Here, then, is the exact wording of Pliny’s description:

Extract 3-F

On her [= Athena’s] Shield he [= Pheidias] chased [caelāre] the Battle of the Amazons in the convex part, while he chased in the concave part of the same shield the Conflicts of Gods and Giants.

Pliny Natural History 36.18 [62]

3§89. The wording of Pliny here makes it explicit that Pheidias was metalworking (verb caelāre ‘chase’) this visual narrative, not painting it. [63] And we see metalworked into the interior of this bronze shield the selfsame narrative that was pattern-woven into the fabric of the Peplos, namely, the myth of the Gigantomachy. From the evidence of ancient imitations of this metalworked narrative, one expert has pieced together a most vivid description: {164|165}

Particularly stressed [in the narrative of the Gigantomachy as metalworked into the bronze shield of Athena] is the presence of Zeus in the centre top of the heavenly arch: other gods converge toward him symmetrically from either side. [Pheidias] seems to announce in this way to the spectator that Zeus is not only in the centre of the battle but also at its culminating point. The same conception is found on the Panathenaic [F]rieze where the human procession, starting from the south-west corner, proceeds in two directions along the north and south sides of the temple to converge over the east end where the gods are assembled to witness the culmination of the ceremony. [64]

3§90. The comparison here with the point of convergence in the narrative of the Parthenon Frieze is most apt. It is at this point in that narrative, as I have noted all along, that we find its defining moment, which is, the presentation of the Peplos.

Linking the robe of Athena to the sculptures on the exterior of the Parthenon

3§91. By now we have seen two links to the Peplos of Athena in the visual art of the Parthenon. In one case, the pictorial narrative that is sculpted into Block 5 on the east side of the Parthenon Frieze in the interior of the Parthenon refers to the form of the woven Peplos. In the other case, the pictorial narrative that is metalworked into the bronze interior of the Shield of Athena is a myth that matches the content that is pattern-woven into the Peplos of Athena, that is, the myth of the Gigantomachy. [65] And now we will see a third link to the Peplos, sculpted into the exterior of the Parthenon.

3§92. I quote from a relevant formulation that I presented in the book Homer the Classic, where I highlighted this third link in the overall context of all the sculptures adorning the exterior of the temple:

On the surface of this exterior [of the Parthenon] are the grand relief sculptures of the pediments and the metopes, featuring a set of connected mythical and ritual themes. The east and the west pediment show respectively the birth of Athena and her victory over Poseidon in their struggle over the identity of Athens; the metopes show the battle of the gods and giants on the east side, the battle of the Athenians and {165|166} Amazons on the west, the battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs on the south, and the battle of the Achaeans and Trojans on the north. So once again we see a sculpted narrative that matches the woven narrative of the Peplos of Athena: it is the myth of the Gigantomachy, sculpted into the east metopes, featuring Athena herself battling in the forefront […]. In this case, the Gigantomachy balances the Amazonomachy that is sculpted into the west metopes. Similarly, the Gigantomachy that is metalworked into the concave interior of the Shield of Athena balances the Amazonomachy that is metalworked into the convex exterior. So the contents of the east and the west metopes of the Parthenon’s exterior correspond respectively to the contents of the concave interior and convex exterior of the Shield of Athena. [66]

Linking the robe of Athena to the Pandora Frieze

3§93. There is a fourth link to the Peplos of Athena in the narratives of visual art adorning the Parthenon. It is the Pandora Frieze, a creation by Pheidias, which he metalworked into the base of the statue of Athena Parthénos. [67] In order to appreciate the significance of this fourth link, I propose that we take the perspective of a viewer standing before the entrance to the temple:

Facing the east side of the temple and looking for highlights that catch the eye, starting from the top, we would first of all see the birth of Athena sculpted into the pediment on high; next, looking further below, we would see the battle of the gods and giants sculpted into the metopes; next, looking even further below and into the interior, we would see the presentation of the Peplos of Athena sculpted into the Parthenon Frieze that wraps around this interior above the columns of the porch. [68]

3§94. What do we see, then, after experiencing these three spectacular views, that is, after beholding (1) the birth of Athena as sculpted into the pediment above, (2) the Gigantomachy as sculpted into the metopes below, and (3) the prototypical Panathenaic Procession as sculpted further below into the Parthenon Frieze? Ascending the steps of the temple and entering its open {166|167} doors, we now behold the most spectacular sight of them all—the gigantic figure of Athena Parthénos standing on top of a commensurately gigantic base. And, at the same time, we also behold, metalworked into the surface of this base, the Pandora Frieze.