-

Manuela Pellegrino, Greek Language, Italian Landscape: Griko and the Re-storying of a Linguistic Minority

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. In the Land Between the Seas

2. “The World Changed”: The Language Shift Away from Griko

3. The Reappropriation of the Past

4. From “the Land of Remorse” to ‘the Land of Resource’

5. Debating Griko: The Current Languagescape

6. “Certain Things Never Change and Those Sound Better in Griko”: Living with the Language

7. The View from Apénandi: Greece’s Gaze on Grecìa Salentina

Conclusion. Chronotopes of Re-presentation

Bibliography

5. Debating Griko: The Current Languagescape

In 1992 the European Council adopted a European Charter of Regional and Minority Languages, which then came into force in 1998. The charter intends “to protect and promote regional or minority languages as a threatened aspect of Europe’s cultural heritage” (European Charter Guidance 2004:3); being the first international instrument focused solely on language, its symbolic contribution cannot be underestimated. Indeed, Italian Law 482 is to be considered one of its important outcomes. Significantly, the Charter represents a shift from previous legal measures supporting linguistic tolerance and protection to linguistic promotion. Through this ideological shift, which sits in the context of burgeoning rights discourses, Europe’s cultural wealth and linguistic diversity becomes “one of the main sources of the vitality, richness and originality of European civilisation” (Ó Riagáin 2001:36). Such celebration of the common European heritage would seem to provide a way to overcome the nineteenth-century linguistic and cultural nationalisms that formed the basis for the establishment of nation-states. Moreover, the emphasis on ‘diversity’ as a symbol of Europe’s richness, and the discourse of ‘unity in diversity,’ have been further promoted by international agencies such as Unesco, and have permeated everyday discourses.

As Susan Gal (2006b:167) notes, however, the emphasis on linguistic diversity is deceptive; the European Charter recognizes “named languages, with unified, codified norms of correctness embodied in literature and grammars”—that is, in order for minority languages to be recognized as languages in their own right, they have to go through a standardization process. Speakers of minority languages are therefore confronted with the expectation to reproduce the dominant ideologies that inform the construction of national languages—together with the attendant challenges—and also to conform to the old ‘romantic/romanticized’ expectations which rely on the same ideological tropes that match ‘a language’ to ‘a people.’ In the case of Griko, the lack of a standard generates multiple ‘language ideological debates’ (Blommaert 1999), which are more recurrent than the use of Griko itself. As typical of a metalinguistic community such as this, locals participate actively in them, and by discussing how to transcribe and teach Griko or how to enrich its limited vocabulary, they reveal their experiential perceptions and ideological projections of the role of Griko in the past-present-future.

By considering in depth locals’ ideologies with respect to Griko’s authenticity, I therefore fill out the cultural temporality of language through which perceptions of morality and aesthetics intermingle with affect, which poses constant challenges to language standardization, change, and to sporadic attempts at renewal. My claim is that for many locals Griko has ultimately become a metalanguage to talk about that past in order to position themselves in the present; moreover, according to the criteria through which locals evaluate the authenticity of language, they also determine who can claim authority over it—and vice versa. The analysis of the current languagescape reveals the repercussions of these debates on community dynamics, and the power struggles that have intensified through the current revival.

The (Non-)Standardization of Griko

According to Bahktin (1981) language standardization goes against the natural tendency towards diversification; it becomes an ideology in itself. Moreover, as in the case of national languages, the standardization of minority languages leads to the stigmatization of certain forms, as certain other forms are valued more and elevated to the status of standard (Gal 2006b:171). This process creates heterogeneity and hierarchy rather than the expected uniformity, Gal continues, and this may lead speakers to question or reject the authenticity of the form chosen as the standard, or to consider their own linguistic forms less adequate and even less authentic by comparison. [1]

Griko does not have a standard; moreover, Law 482 does not distinguish it from Calabrian Greek. Despite considerable differences, Griko and Greko are nevertheless joined under the label of ‘the Greek linguistic minority’ on Italian soil. Griko itself is, in fact, characterized by internal lexical and phonetic variation among the villages of GS—what in technical terms is called diatopic variation, and which applies also to Calabrian Greek. This means that several variants of the same word may exist, or that the same variant may be pronounced—and thus become written—differently while remaining, by and large, mutually intelligible. When in the late 1970s the linguist Alberto Sobrero investigated the diachronic transformation of Griko by comparing his data with those provided by Morosi in 1870, not surprisingly he noted the influence of the Romance dialect and Italian at the lexical level. More interestingly, he pointed out that words reported by Morosi as being used in only one village were then also used in other villages ( gruni, ‘pork,’ was used only in Corigliano and now also in Castrignano and Calimera). Moreover, what Morosi had indicated as a characteristic form of a specific village was no longer to be attested there, but elsewhere: magrà, ‘far,’ was used in Sternatia and larga elsewhere, whereas in the late 1970s the latter form prevailed in every village except Soleto. These linguistic shifts do/did not depend on the influence of the Romance dialect or Italian; rather, Sobrero argued, they attest to the erosion of the linguistic system due to the fact that each village reacted differently and at different times to its isolation from the Greek spoken around Greece (Sobrero 1979). If the absence of a hegemonic center explains historically the absence of a ‘standard’ Griko, today, locals’ resistance to the standardization of Griko assumes a new significance, as I move to discuss.

***

It was a rather chilly Wednesday afternoon in early November. Adriana and I had arranged to meet at her place to then go for a walk through the village, but because of the tramontana —the northern wind—the temperature had dropped considerably. We decided instead to stay in. Adriana from Corigliano was one of my first informants who soon turned into a friend. She is in her early 50s, and unusually, given her age, a mother-tongue Griko speaker—she had grown up in a Griko-speaking environment and would always hear her mother communicating in Griko with their neighbors. To her, in contrast, her mother would speak Griko only in specific contexts and for specific reasons. “She would use it when she didn’t want us to understand and always when she had to reproach me and my sisters. And that often happened … It worked with us, so I use my mom’s methods with my nephews too to transmit the language” (see Chapter 2), she explained on another occasion with a laugh. At the beginning of our frequentations, we would switch between Italian and Salentine; as I improved my Griko, she used it with me more and more often.

As she handed me a cup of coffee she had just made, I thanked her saying, “ Kalì sorta ”—literally “Have a good destiny”— sorta being a borrowing from Salentine (Italian: sorte). “That’s how you say it?”, she asked me, “I hear it here too sometimes, or people may just say ‘Grazie’ [Italian]. When I go to the gas station, I always thank the guy saying, ‘ Na stasì kalò’ [literally ‘May you be well’].” The conversation about the different ways to say ‘thank you’ kept us busy for the next ten minutes. Kalì sorta apparently was meant to be used only by someone older to thank someone younger; in some villages, such as Sternatia, people tend to use Charistò. I commented that I found it hard at times to memorize the lexical differences characteristic of the various villages, and the preferred the choices of the villagers; that’s when she suddenly exclaimed, “This is a language which has been transmitted orally. Its variation is its richness; is there anything nicer than this? I am going to find the script of Loja Americana [American Words], and you will see what I mean.”

A few years earlier Adriana had gotten involved in the performance of this hilarious play, which builds on a number of misunderstandings arising from the use of a couple of English loanwords. It was by Prof. Tommasi—a retired teacher and one of the most respected local Griko scholars—in an alternation of Griko, Salentine, and Italian. I could guess what she meant before she went on to explain, as I had already viewed the tape of the performance: in it, every actor used their own language variety, effectively creating a polyphonic performance. I had also met with Renato from Calimera, who directed it; he was very enthusiastic about his accomplishment, and proud of having involved amateur actors from various villages in Grecìa Salentina: “I think it is right to respect the local variants; it is more popular and democratic. So, I say kecci [small], but you say minciò ? Say minciò then!”, he had remarked.

“Playing in Loja Americana was real fun, Manu!” Adriana said, giving up looking for the script, “I will find it though, and you can photocopy it” (and she did, a few weeks later). Her mobile phone rang; it was her sister, who asked Adriana to collect her son from his soccer training. As we were leaving the house to fetch her nephew we commented on how cold the weather had turned. So I said, “ Pao na piako t'asciài atti' màkina, kajo ”—“I’d better take the hat from my car”. She immediately intervened in Salentine, “You say kajo [better]—that’s right. Here we say kaddhio.”

Like Adriana and Renato here, locals generally value the richness of Griko that comes from its internal variation and often comment upon those variations, at times at the expenses of the communication itself. The frequent interruptions to highlight and/or clarify differences often put a conversation in Griko on hold, turning Griko itself into the topic of the conversation, as I have argued elsewhere (Pellegrino 2016b). [2] Pronunciation is always noticed—as Adriana did a few times that afternoon too—since it indexes the village of origin: apart from the ‘smaller detail’ mentioned above (kajo / kaddhio) the major differences refer to the Greek letters ψ (ps) and ξ (ks); these are pronounced differently in the various villages (e.g., fs, sc, ss, ts); so, for instance, the Greek ψωμί, or psomì, (bread) is pronounced sciomì in Zollino and Castrignano, and tsomì in most of the other villages; similarly, the Standard Greek ξέρω (to know) is pronounced scero and tsero, etc. As I can attest first-hand coming from Zollino, the pronunciation used is this village is often a source of comment, and is occasionally the target of humorous remarks, indexing a minority within the minority, so to speak. [3] Speakers often recognize and may even use (jokingly or accommodatingly) a lexical or phonetic variant from another village, while making the point that ‘that’ variant is not ‘theirs.’

Indeed, while we were getting in her car, Adriana recalled another project she was involved in that had been carried out in my home village; this was about the Easter tradition I passiùna (see Chapter 3). She found it hard to sing using Zollino pronunciation, she explained, and so she sang in ‘her’ Griko from Corigliano. She is not the only one, of course. “There is no way I can put something different in my head from what I’ve always said and heard. Never and never (Italian: Mai e poi mai),” she firmly concluded. Locals’ attachment to their own variety, to a specific pronunciation and/or lexical choice, is indeed widespread, rendering ‘language standardization’ something of an off-limits topic. It could be argued that this stems from a form of ‘linguistic campanilism’, with a village’s campanile (bell tower) being emblematic of the smallest discrete unit of social/linguistic identification. [4] There is, however, more to it.

As she drove through the village she passed near the house of an elderly lady she was close to while growing up: “When I went to visit her she would always say, ‘ Na, irte o ijo-mu essu ’ [The sun arrived in my house],” Adriana remembered, moved. Then she pointed out to me the neighborhood where she grew up, commenting that she has nice memories of her childhood, although her father had migrated to Switzerland and spent over twenty years there. “We used to live in a casa a corte (see previous chapter) also with Nunna ’Ndata. She was a widow; her husband died at war,” she said, using the typical way of referring to older women one is close to as nunna, which conveys a sense of familiarity as well as respect. She then continued to recount details of this neighbor’s life with particular accuracy; with the same attention to detail and affection she also recalled how in the evenings, together with her sisters, she would sit by Nunna ’Ndata's door step: “The light was always off!”, she emphasized as if she were trying to recreate that scene, “and she would tell us stories [Salentine: ci cuntava li fatti] and often in Griko; she did not have TV and she didn’t want one until she died.”

As we were approaching the spot where her nephew was waiting for us, she shifted to comment on how well the heating system of her old car still worked. I agreed, and added that the tramontana wind had been giving me a headache all day. She teasingly asked me, “Do you have rheumatisms in your head?”—“ Echi reuma so kòkkalo? ” That led her to mention an anecdote about her grandfather, who once jokingly complained about his wife talking too much by saying, “ Eh ’Ntogna! Echi reuma ses anke, reuma sa chèria, reuma so kòkkalo, ce si' glossa 'e' s'orkete mai? (Greek)—“You have rheumatisms in your legs, hands, head and it never affects your tongue?” Adriana had inherited his sense of humor; we meanwhile collected her nephew and were heading back to my car.

As we see with Adriana here, specific words and expressions are not ‘just words,’ nor ‘simple expressions,’ but become images of and from the past, which are linked to locals' personal memories of language use. Each word chosen, each sound reproduced, is an echo of someone else or of a specific moment in time—Bahktin (1981) indeed had it right a long time ago. Locals hang onto these, as they evoke the memory of others who had uttered them, connecting them across time and beyond phenomenological distance, mobilizing vivid emotions. This way the ‘textures of Griko’ become palpable; indeed, its materiality made up of both sounds and images reveals itself as it engages people in recalling a story linked to a specific word or expression, which in turn elicits an anecdote from their past. I have witnessed this countless times. Keeping that specific word, using that specific expression, and pronouncing a word in one particular way or another become therefore ways to keep the past alive, together with the memory of the people who inhabited it. If today Griko is no longer used primarily as a language of daily exchange, memories of language use are ‘alive’ and contribute to shaping its use up to the present, as I also show in the next chapter. In this sense, the material presence of Griko is all around through its sounds and forms. This may also explain, I contend, why no village variety has so far prevailed over the others, and also why attempts to standardize Griko have always been challenged in the name of the local declination of ‘unity in diversity.’

This applies also to the local language teachers—who are referred to as ‘language experts’ (Italian: Esperti di Griko)—and to local Griko scholars. A few years later Adriana and I would get involved in a project called Pos Màtome Griko (How We Learn Griko); it was financed by the European Commission, and aimed at the development of teaching materials for Griko as a way to address the lack of dedicated textbooks. Having taken part in the project I can attest that it was fraught by various challenges, to which I will return. [5] Tellingly, however, the possibility of creating a standard was briefly mentioned and soon collectively dismissed on the basis that “it would be detrimental to Griko’s richness and historical development,” to use Prof. Tommasi’s words. He was involved in the project, together with Giorgio from Sternatia and Sandra from Corigliano, while Adriana acted as a consultant in her capacity as a mother-tongue speaker. Indeed, the outcome of this project differed from the original vision: each of us compiled the various CEFR competency levels (A1, A2, B1, B2, etc.) drawing on our own village variety. The resulting polyphonic structure may create difficulty for new learners and readers, as the critique goes.

Yet what prevails is the view that “No local Griko has, or should claim any superiority over the others. No Griko speaker can presume to teach Griko to another speaker,” as Paolo from Martano phrased it. There are also pockets where it is still believed that “the Griko from Calimera is more correct” based on the misplaced assumption of its stronger affinity with the Greek spoken in Greece. Such comments also originate in the prestige associated with intellectuals’ activities within the ‘philhellenic circle of Calimera’ (see Chapter 1). Largely, however, locals do not rank Griko’s variation internally. By valuing it and Griko’s ‘unity in diversity,’ locals ultimately resist language standardization, and will likely continue to resist it as long as experiential memories of language use persist. Yet, while the Pos Màtome Griko project received a mixed reception, it was appreciated that it involved local Griko teachers. One of my informants pointed out to me, “At least you avoided cold interventions from external language experts, linguists, or ‘aficionados’ (Italian: appassionati) of Griko who don’t really know us and expect to come and teach us our own language.” On the one hand this highlights how the latter are perceived as lacking the experiential, material and affective dimension of the lived use of the language, which is itself embedded in time and memory; on the other hand, it points to intellectual property issues and the power struggle over who retains authority over Griko and cultural heritage more broadly, which I introduced in the last chapter, and to which I will come back.

The Limits of ‘unity in diversity’: The teaching of Griko

The teaching of Griko in schools is a highly contested matter. It is also the language domain that faces the biggest challenges, and where the limits of the ideology of ‘unity in diversity’ reveal themselves. At a discursive level, Griko’s unity in diversity would seem to find support in the school setting. This is how the then-schoolmaster of Castrignano, Professor Nucita, phrases it in one of her articles:

However, in practice, the limits of applying these views soon emerged. Prof. Greco from Sternatia indeed complained openly that, at the moment, the reality is rather different than the theory: If for the current academic year a teacher from Calimera is appointed, she would teach the Griko of Calimera; the following year, however, a teacher from Corigliano might be appointed, and she would teach the Griko of Corigliano. “Children therefore find enormous difficulties” in learning the language, Prof. Greco said. Indeed, the teacher’s variety of the language almost inevitably becomes the default standard for each classroom, at times provoking reactions from parents, while teachers are not necessarily nor equally competent in every village variety, and their mobility from one village to another according to the school year complicates things further. [7]

We overcame the dilemma of the variants that our language shows … We agreed that ‘diversity’ keeps enriching ‘diversity,’ as every community, through its specific language expresses its own social and evolutionary history. The phonetic and graphic diversity of the lexicon of every village is certainly linked to the evolutionary history of the specific territory … We adopted a diversified method: to introduce children to the variants of other villages, comparing them to the variant of their own village. [6]

In order to grasp these intricacies, I undertook participant observation of weekly Griko classes at primary schools, rotating through the villages of Grecìa Salentina over a two-month period. What immediately became evident was that Griko was not taught in the old normative scholastic way. Giovanna, for instance, would resort to teaching her own poems—which were beautiful, I might add—in her classrooms. Sandra and Maria would translate contemporary songs into Griko, such as ‘YMCA.’ Ivana would use Pantaleo—a rabbit she would create on the spot from a handkerchief, as grandparents used to do—who would then interact with the children in Griko. Giorgio, instead, experimented with teaching Griko and Modern Greek comparatively in collaboration with the MG teacher sent by the Greek Ministry of Education; at times he would use articles written in Griko from the local journal Spitta.

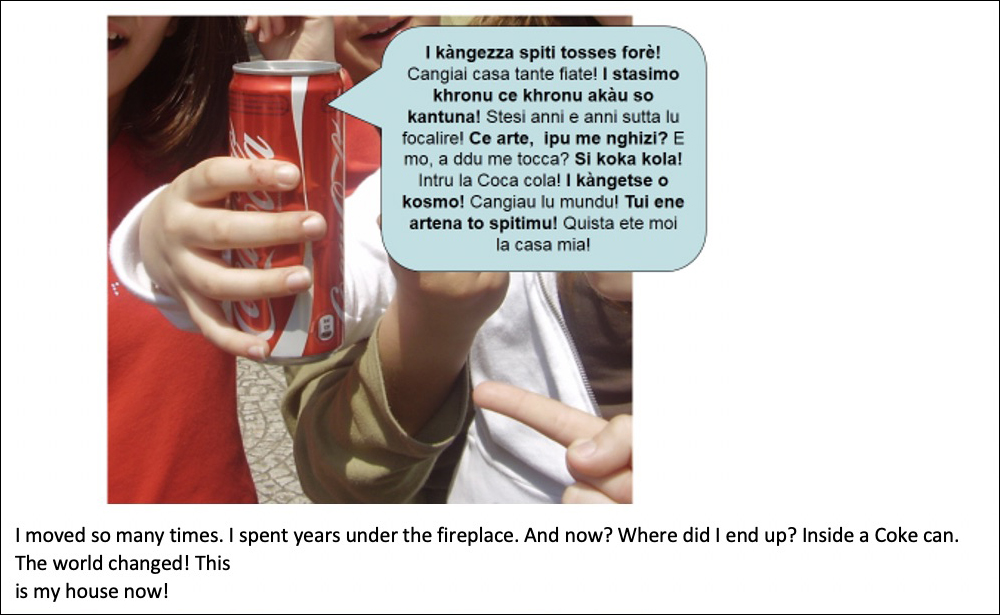

When I first interviewed Griko teachers they constantly mentioned the lack of a standardized Griko orthography, and of dedicated teaching material (at the time) as the biggest issues they had been encountering. Interestingly, however, even after the publication of Pos Màtome Griko, this has not been adopted as a textbook by all Griko experts, and even Giorgio and Sandra make partial use of it. Indeed, Griko teachers often privilege teaching schoolchildren poems, songs, and popular rhymes in Griko, while the wider repertoire of popular culture and the importance of the language, its history, its traditions tend to be presented discursively. At the end of the school year, each school often organizes initiatives such as theatrical or musical performances, in which the children are the protagonists, and ‘perform’ using the knowledge of Griko they had acquired during the classes. In other words, the teaching of Griko in school is not aimed at the production of new speakers but rather at conveying and replicating past cultural and linguistic artifacts. Figure 22 below is a good example to this effect and is taken from the teaching material provided by Sandra.

Figure 22: Teaching material. Photograph courtesy of Sandra Abbate

The text provided here alternates between Griko and Salentine. It makes reference to the goblin of popular tradition—the Sciakùddhi—who, in order to adjust to modern times, migrates from living in the fireplace to living inside a can of Coke. Griko experts therefore continue to draw on the wider repertoire of popular culture (see Chapter 3), but they purposively ‘adapt’ it to contemporary life, trying out innovative ways of presenting Griko—in dialogue with the past, but recontextualized in the present. This was indeed Sandra’s aim, she said.

Sandra has been teaching Griko since 2002, and when I asked her to tell me which of the projects carried at school she considered most successful, without hesitation she mentioned the Orchestra Sparagnina (Italian). The Sparagnina Orchestra involved about thirty schoolchildren—now young adults—from the school of Corigliano, who, over the course of ten years, learned to play instruments such as accordion, tambourine, guitar, and percussion, and to sing the traditional repertoire of songs in Griko, learning fragments of the language along the way. We see here the relevance of music in the transmission of language—however partial—and how they are mutually supportive: playing/singing the Griko repertoire enhances language learning, and is also fun; by learning, Griko students can fully appreciate its musical/performative expressions. Sandra has successfully dragged her entire family into singing and playing Griko at cultural events dedicated to Griko, and she is proud that she managed to transmit to her eldest daughter a passion for the language. Sandra’s daughter Tina now teaches Griko to children as part of a project funded through the regional law. “As long as we pass on the love for the language, we fulfill our task. Anyone who teaches knows that the results come with time; some of these kids may get involved with Griko in a few years, when you least expect it,” Sandra added.

As for the popular reception to the teaching of Griko, if we compare the finding of the Lecce Group in the late 1970s with a recent sociolinguistic survey by Alberto Sobrero and Anna Rita Miglietta (2010) and Miglietta (2009), we read that 45 percent of the sample in Sternatia and 42 percent in Corigliano consider it an effective way to preserve the language. However, there have been instances in which parents rejected the teaching of Griko, as happened in Soleto in 2005; indeed, Article 4 of Law 482 states clearly that the teaching of minority languages depends “also on the basis of the request of the children’s parents.” According to the schoolmaster, this instance might be singled out, since Soleto (together with Melpignano) is a village where the language shift away from Griko happened towards the end of the nineteenth century; parents’ cold reception toward teaching Griko could be linked to a lower sensitivity to the topic, he argued. Percentages and villages aside, there is certainly a wide divide, as there are parents who show personal attachment to Griko and welcome its transmission—albeit through the teaching of its cultural heritage. At the opposite end, there are parents who instead lament that Griko takes up time that could be more fruitfully spent teaching children English. Indeed, the teaching of Griko in school would seem to confer the minority language the same symbolic capital as Italian—or English, for that matter. However, by striving to reproduce the dominant language ideology, Griko may keep losing out and being perceived as a ‘recreational’ subject, depriving it therefore of the ‘seriousness’ of other languages and subjects. It seems that Griko does not mix well with the normative monolingualism historically dominant in such an institution, and that locals at large do not challenge that assumption. Rocco phrases it differently: “The death of a language is the school. When you impose a language in the school, it means that it is dead. No one learns a language at school.”

The ‘politics of orthographic representations’

Although Griko lacks a ‘standard,’ in recent years it has interestingly been enjoying a renewed life in its written form, thanks to the activity/contribution of local scholars and laypeople alike. The journal Spitta (Spark), written in Griko and published since the end of 2006, is a typical example. Giuseppe from Martano, a retired schoolteacher, is one of the editors and a passionate activist for Griko. As is often the case among those belonging to the ‘in-between generation,’ he is a Griko ‘semi-speaker’ who was not taught Griko as his mother tongue, and who has been increasingly engaging with the Griko cause; for over a decade he has also tenaciously been compiling and curating a website which includes grammatical tables, as well as recordings of elderly speakers, their transcriptions and translations into Italian.

Commenting on this initiative he pointed out that how to transcribe Griko was one of the first and largest issues Spitta encountered. This shift from the traditional oral use of Griko to its current and predominantly written use poses its own challenges. Indeed, if until the fifteenth century the Greek alphabet was utilized (see Chapter 1, especially the activity of the Monastery of Casole), since contact between Salento and Greece receded, Griko survived predominantly as an oral language; this was the case until the end of the nineteenth century, when the exponents of the circle of Calimera started writing again, mostly utilizing a transliteration in Latin characters (see Chapter 1). A proposal to go back to using the Greek alphabet has been put forward, but so far it has not found many advocates on the grounds that this would alienate the speakers themselves, becoming a language only for experts and aficionados. Not surprisingly, there is still no local consensus on how to transcribe it, while, interestingly, all activists claim they aim to ‘facilitate’ the reading of Griko; this is the principle on which they base their choice of the orthographic conventions adopted—however different they may be. [8]

Figure 23: The Journal Spitta

Indeed, Giuseppe knows that one of the strongest criticisms raised against Spitta relates to orthography, as the articles published do not conform to the same conventions and present a wide variation. As seen in Figure 23, on the right-hand side, the sound of the Greek ‘χ’ is represented as ‘ch’ (as in chrono), mirroring the most commonly used transliteration of Greek. The language reference here is Standard Modern Greek. On the left-hand side, it is instead represented as ‘h’ (as in eho), whereas ‘ch’ stands for ‘k’ (as in checci), taking as reference the Italian language. Significantly, the very choice to refer to the Italian or Greek alphabet to write Griko reveals different ideological alignments and projections; it ultimately indicates how writers have in mind a different set of final readers: the Italian or Greek audience—or people who know or have studied Greek. While in the first case Griko speaks for locality, in the second case it is projected as one of the languages of Hellenism in the world, so to speak. Apart from the ideological and political implications of these choices, the reader is put into distress.

Daniele from Calimera is one of the most refined connoisseurs of Griko, and feels strongly about these issues: “It seems absurd to me to write in the Greek alphabet; we shouldn’t do it because we have a whole series of palatal, semi-consonants and one cacuminal sound that you can’t reproduce with it. Language is a protocol.” Because of its hybridity, Griko requires a phonetic transcription for which both the Greek and Italian alphabets are insufficient or inadequate, Daniele argues. Advocating coherency and simplicity, he has proposed a writing system that addresses the multiple local pronunciations by using the Latin symbols xi and psi to reproduce the letters ψ (ps) and ξ (ks) of the Greek alphabet, going back the origin of the words that contain them. For instance, the Greek ξέρω (to know) is written xero instead of scero / tsero / ssero ; the Greek word ψωμί (bread) is written psomì instead of sciomì / tsomì / ssomì. This would provide a standardized approach “which overcomes localisms and aims to write Salentine-Greek in a way in which everyone can recognize themselves, including the Greeks” (Palma 2018:109). [9]

This debate is not confined to culturi del Griko, or language activists and experts; it permeates and reaches literate Griko speakers, becoming a topic of concern and dispute in which they passionately participate in conversations and in online forums. “Everyone writes as he pleases,” one informant told me, on the grounds of either simplicity or closeness to the oral form. “Everyone writes as he hears it, or as he can,” he then added. The result is an appreciable range of orthographic variation among the written texts that circulate, also due to the fact that even the same individual may at times be inconsistent with his own criteria or change them over time. Meanwhile, as Alexandra Jaffe (2003:521) notes for Corsican, “in the absence of any kind of recognized language academy able to impose one official orthography, the orthography debate stands as a conventionalized public discourse used by people to express their views about the nature or the state of the language.”

Giuseppe humbly acknowledges the limitations of the journal Spitta : for those who write, the stumbling block is indeed the orthographic representation. As for the reading audience, there are two issues, he says: “Elderly Griko speakers often cannot even read; if they can, they find huge difficulties in reading Griko. Those who can read but do not master Griko have difficulties too.” Certainly, elderly literate Griko speakers struggle to read this journal. This may be in part linked to their limited exposure to the practice of reading in general; or the difficulty may lie in the very practice of ‘visualizing’ what they have only ‘said or heard.’ Add to this issue that reading is not an interactional practice that presupposes a human encounter, as they are used to: the result is that elderly literate Griko speakers may find reading Spitta a lonely enterprise, alienating and frustrating at times, leading some of them to argue that “This is not Griko.”

Ideological debates about Griko

The Kaliglossa (Good Language) cultural association from Calimera is particularly linked to the Griko–Hellenic Festival, an annual initiative that first took place in 2007 and went on for a few years; the inaugural festival, as well as that of the following year, centered on a poetry, music, and theater contest in Griko, while an Ancient and Modern Greek language contest was incorporated from year three onward. The following is excerpted from the association’s website:

The contest’s regulations, interestingly, make it clear from the outset that,

These words reveal clearly that the association’s activism is not aimed at language revitalization as such, which would upgrade Griko and render it again a language of common use and communication, as it were. The association instead fosters its knowledge by promoting the written production of an ‘authentic kaliglossa,’ aiming more at language restoration. Language shift has indeed led to further linguistic erosion and to the impoverishment of Griko’s vocabulary, as speakers have ‘forgotten’ words and replaced them with borrowings from Salentine and Italian, although grammatically adapting them to Griko. As Grazio from Sternatia characteristically put it, “ To griko ka kuntème àrtena? Durante sti strada fìkamo tossa loja ka ’e tâchume pròbbiu stennù plèo’ ” (Griko)—“The Griko we speak today? Along the way we abandoned so many words and we don’t remember them any more.” These dynamics have not surprisingly led to the emergence of a personalized and ‘intimate’ vocabulary unique to the speaker—what in linguistics is labeled idiolect.

[The association] is aware of the difficulty of proposing the Griko of today as a language of common use and communication. Yet it tries to foster its knowledge through adequate acquisition strategies and through the circulation of written texts. In this regard, it strives to stimulate and encourage the writing of new texts (poetry, music and theatre) with the aim of enriching the already notable literary repertoire in this language. (my emphasis)

The jury will select those compositions which follow the spirit of an authentic kaliglossa [good language] and will take into account how the authors use the lexical repertoire of each language, limiting to the minimum the recourse to foreign words. It is furthermore requested an accurate and coherent phonetic transcription of Griko. (my emphasis)

The linguistic recovery of forgotten forms therefore becomes one of the issues debated locally; it regularly emerges in my encounters with Daniele, who used to be a member of the Kaliglossa association. This is how he addressed it: “The Griko we speak in Calimera lacks a word for ‘feast’ for example, so we use festa [Italian/Salentine loanword]. In Sternatia, however, they use jortì, which coincidentally corresponds to MG too. Well, in such cases, I propose to use the Greek-deriving word if this is present in neighboring villages.” These constitute, he argued, instances of linguistic recovery. Similarly, Gianni De Santis from Sternatia purposely used, in his songs, Griko words that had fallen into disuse, but which he learned from his grandmother, thus enacting instances of linguistic recovery. How far back in time to go to restore Griko and retrieve words of Greek origin is another matter altogether; when the topic arose it initiated debates about whether to resort to oral memory—as Gianni did—or whether to use the written material starting from the nineteenth century onward. This would effectively mean resorting to the pioneering work of the linguist Morosi, and to the collection of oral tradition provided by early cultori del Griko at the turn of the twentieth century—which in turn opens up discussions about the kind of sources to use and their scientific reliability. [10]

The Griko–Hellenic Festival contest’s regulations interestingly embed an explicit invitation to authors to avoid resorting to foreign words in the name of an authentic kaliglossa. Daniele often reiterates, “The authenticity of Griko is my obsession, to use a language as pure as possible and as purified as possible from dialect and Italian.” More than once he poignantly commented, “Let’s keep at least what we had!” For instance, once he heard me using the expression ‘ kàngesce o kosmo,’ as I do quoting my elderly friends (see Chapter 2). He reacted by saying I should use the Griko verb “ addhàsso,” mostly fallen into disuse, instead of “ kangèo,” which is an adaptation from the Salentine “ cangiare ”—and thus to say “ èddhasse o kosmo.” Linguistic recovery is hence also a way to ‘purify’ Griko. Not incidentally, Daniele used this very verb; this indicates how he rests on and reproduces the language ideology promoted by the philhellenic circle of Calimera (see Chapter 1). The use of adaptations and/or borrowings from the Romance dialect or Italian to compensate for forgotten terms, and/or to implement Griko’s restricted vocabulary, therefore should be/is scrupulously avoided.

In such instances we see at play the legacy of the old-fashioned ideology of the past, which saw Griko as a ‘bastard language,’ as a ‘contaminated language,’ because of the presence of Salentine borrowings or adaptations. Metalinguistic practices such as these highlight an underlying ‘purist language ideology’ that considers Salentine as an agent of contamination of the perceived original ‘purity’ of the language pre-contact. Here authenticity is defined on a temporal scale; the further back in time you go, as it were, the less contaminated, thus the more authentic, Griko you will find. The ‘authentic’ Griko is therefore defined based on its distance from Salentine/Italian interferences.

The internalization of this ideology is indeed nothing new; what is new is that speakers, activists, and cultori del griko are now metalinguistically aware of it. They ‘police,’ as it were, the linguistic boundary with Salentine/Italian, and tend to highlight and sanction each and every word in Griko, which they readily recognize as adapted from them—again at the expense of the conversation itself. This folk appropriation of the ideology of ‘purity,’ has led to what Deborah Cameron (1995) has defined as ‘verbal hygiene,’ leading some speakers to even apologize when using words borrowed or grammatically adapted from Salentine or Italian; they feel uncomfortable when they cannot meet the expectations to speak a ‘pure’ Griko. This discomfort can also happen in interaction with Greek tourists visiting Salento, or with linguists conducting research in Grecìa. This phenomenon has, in fact, interested mainly those speakers who have followed and participated in the revival mechanism more closely. My informants from Sternatia, for instance, are very self-conscious about this ideology, partly because they attend Modern Greek classes in the Chora-Ma association and have been learning some MG, partly because Sternatia is the village most visited by Greek tourists. These dynamics, in turn, have important implications for the future envisaged for the language and the community’s self-representation.

Another language ideological debate that engages activists and speakers is whether and how to implement a language that lacks a ‘vocabulary of modernity’. This is often the case with minority languages whose communicative functions have diminished over time due to language erosion and shift. Since the severing of contacts with Greece, Griko was progressively excluded from various linguistic domains and came to be increasingly associated with the rural world, while speakers have kept creatively incorporating Salentine and Italian resources to fill its gaps. Daniele told me that there had been internal discussions among the members of the Kaliglossa association about the proposal to replace borrowed or adapted Romance words with standard Greek words, but that no agreement had been reached. He pointed out his personal doubts that recourse to Greek would be a good solution: “I fear Greek could kill Griko, but not everyone agrees with me,” he added (to be sure, scholars such as Rohlfs and Karanastasis argued against the use of Modern Greek, which would de-historicize the language, a view that is still common among Greek linguists). Instead, Daniele was very pleased to point out that one of the editions of the Festival contest was won by an entrant from Sternatia who had inserted in his poem the term jinekosìni, a neologism that contains the word jinèka (woman) and the suffix sìni (the quality of); that is, ‘femininity.’ Neologisms of this kind, he argues, respect Griko without altering it.

Daniele ultimately argued that in order to preserve the authenticity of Griko, any MG term should be avoided; introducing them, he explained, would be “an artificial intervention.” Renato from Kaliglossa equally pointed out that they make the effort to use the existing terms in Griko as much as possible, but he added, “If Griko does not have a word for something, you cannot invent it.” Referring to such a practice, he concluded emphatically, “This way they create a fake Griko because when Griko lacks a word, they insert it from MG. It’s not right! It’s like when you restore a painting; if a piece of it has disappeared and you paint over it, you are creating a fake. Instead you should leave a blank spot there, that’s all.” Tellingly, Silvia from Calimera, rather uncomfortably confessed to me: “I sometimes use Modern Greek, especially when returning from Greece I end up getting confused for a while, but I feel I betray Griko this way.” Her metalinguistic comment about “betraying” Griko when/if using MG borrowings or adaptations reveals an implicit moral judgment.

Indeed, we see how what is considered ‘authentic’ and ‘fake’ becomes a matter of what is ‘right’ and ‘wrong’, highlighting the moral dimension in which debates about Griko are embedded. MG ironically might end up reclaiming the unfortunate definition of ‘agent of corruption,’ of ‘contamination’ of Griko, just like Salentine, and it is morally sanctioned for potentially ‘killing Griko.’ Just like with Salentine, the linguistic boundaries between Standard Greek and Griko are indeed watched over; also those cases in which the confusion with/interference of Greek is momentary are promptly noticed and commented upon, and often sanctioned, thus calling into question the competence and also the authority of the speaker. I personally witnessed a Griko speaker from Zollino, who also knows Modern Greek, being harshly criticized for having ‘mistakenly’ used the standard Greek term paraskevì (Friday) instead of the Griko equivalent parassekuì / parasseguì. I was also personally reproached for getting confused and using the Greek proì (morning) instead of the Griko pornò.

To be sure, conscious attempts to integrate Griko with Modern Greek have occurred in the past. One example is Cesarino De Santis’s literary production in the 1970s, in which some poems make extensive use of it; or Domenicano Tondi from Zollino, who in the 1930s wrote a Griko grammar heavily influenced by MG, with the aim of creating a Griko koinè. Both of them are criticized for creating an ‘abstract’ language. Prof. Sicuro, instead, did not share fears about the impact of MG on Griko. He insisted on the importance of MG, and would summarize effectively his position by saying that, “Griko has no future. The future of Griko is Modern Greek.” Griko on its own, he argued, would bring only isolation; his wish was therefore to project Griko as a language which could enable global connections. Indeed those who share an ideological fascination with ‘all things Greek’ look at MG as a reference, considering it not only as a source of prestige but also an agent of the renewal of Griko and hence a source of inspiration to create neologisms by resorting to Greek calques. Antonio from Zollino exemplifies this position. He has been attending MG classes at Chora-Ma for the last ten years and vehemently supports his proposal to introduce into Griko the MG term àniksi (spring) due to the presence in Griko of the verb anìo (open). This reasoning provokes the reaction of Mimmo, who does not agree with the introduction/creation of terms such as spring and autumn, since this would go beyond “the Griko temporal rhythm,” as he put it, which was characteristically set by only two seasons (winter and summer, to scimòna, to kalocèri). Antonio is also among those who advocate the use in Griko of the term biblio for ‘book’ instead of libro, a term that speakers borrow from Italian and adapt grammatically to Griko; he further supports this choice by referring to the fact that, even in Italian, we use the word biblioteca for library. In this respect, the intensification of contact with Greece, the availability of MG courses provided by the Greek Ministry of Education, and the interest shown by Greek aficionados of Griko who have visited the area since the 1990s have all contributed to this. These contributions have indeed impacted the language ideologies and practices of those who have been involved more closely in the dynamics of Griko’s revival, further influencing their language choices and ‘tastes.’

Interestingly, Griko mother-tongue speakers from Sternatia who have attended Modern Greek classes also tend to resort to Modern Greek, particularly when meeting Greek tourists. Here, however, the use of MG is conscious and not due to extemporaneous confusion, as was the case of Silvia from Calimera above: it simultaneously becomes a way to ‘show off’ their knowledge of MG and a way to facilitate conversation with Greek visitors—here what takes precedence is the value of language as medium of communication (see also Chapter 7); in contrast, they do not resort to MG when speaking among themselves, or to other Griko speakers from nearby villages.

Figure 24: The sign of a bakery shop, Martano. Credit: Theodoros Kargas

The constant search for the Greek flavor of Griko may also create funny examples (see Figure 24). Panetteria is the Italian word for ‘bakery,’ while artopoieío in MG means literally ‘the place where bread is baked.’ The story goes that the owner of this bakery in Martano wanted to use Griko in his shop’s sign, and asked Prof. Sicuro for help. As Griko lacks such a word, Prof. Sicuro suggested the word artopoleío, an MG word that means ‘the place where bread is sold.’ He pointed out, however, that this term would not be understood by Griko speakers—and, I will add, they would not be able to read it, as it is written using the Greek alphabet. What Prof. Sicuro probably ignored is that the word artopoleío is seldom found on shop signs in Greece. The common term is, rather, artopoieío, or praktorío ártou or furno, the final one curiously being borrowed and adapted from Italian!

Between the Past and the Future: Stuck in the Present

In one of my first encounters with Giuseppe, he defended the initiative of the journal written in Griko by stating that, “ Spitta represents the only testimony of the real Griko—of today’s Griko, I mean (emphasis and reiteration in the original). Although there are many publications of poems in Griko, in these instances the language is sought and refined; in a word, it is artificial, hence not the spontaneous spoken language.” By stressing that Spitta exemplifies the ‘real Griko,’ he accuses of ‘artificiality’ those initiatives that privilege and foster the ‘poetic’ written modality, such as that proposed by the Griko–Hellenic Festival, although he did not specifically refer to it. What these initiatives have so far shared is the view that integrating Griko’s vocabulary with MG terms “would contaminate and denaturalize our language,” as one of Spitta ’s founding members stated.

Giuseppe in fact follows a sort of fieldwork strategy in writing his articles, recording elderly mother-tongue speakers narrating an event, then reporting the narrations faithfully. “Whichever its limitations, Spitta is a snapshot of Griko!”, Giuseppe emphasized. He therefore defines Griko’s ‘authenticity’ not by the ‘notable written production’ of scholars, but by its closeness to the contemporary language, proposing it in a prose modality. This presents hybrid linguistic forms, mixing Griko with Salentine (and Italian), but such a hybridity is perceived as a form of continuity with past practices, and this is what renders the language ‘authentic’ in its own right. The attempt of the Spitta initiative is backed up theoretically, as linguistic compromise and the acceptance of hybrid forms enhances the language’s survival chances. [11] This has indeed contributed to the ‘survival’ of Griko up to the present; in fact, Griko speakers from Sternatia—which is popularly held as the village with the highest percentage of Griko speakers—characteristically rely more heavily than nearby villages on hybrid forms and borrowings from Salentine/Italian; this allows them to speak fluently also about the themes of the present. By contrast, as linguist Nancy Dorian argues, puristic attitudes may “create problems for efforts to support minority languages” (1994:480).

In the linguistic continuum from more purist towards more accommodating language ideologies, Giuseppe and the contributors to the journal are among those who are more acceptive of hybrid forms, neologisms and calques, as Spitta’s articles show. The journal’s aim, as the title itself declares, is to make Griko ‘sparkle’ instead of linking it to and segregating it from an ideal and/or pre-contact past. Indeed, he is proud that the journal engages with contemporary topics, in this way embracing a language ideology that links Griko to the ‘present’ and thus projects it into the future. Giuseppe’s personal aspiration is to act as a connector among generations and inspire young people to learn and speak Griko, providing them the tools to do so. Those enthusiastic about this initiative proudly claim that Spitta is proof that Griko is ‘alive,’ expressing their animosity towards those who did not believe it would ‘survive,’ including the scholars who had predicted its death and the politicians who had long not invested in it. Popular reception of this journal, however, ranges from enthusiasm to open criticism, revealing the multiplicity of language ideologies in interaction and the deriving tension stemming from the polysemic local understandings of what ‘authentic’ Griko stands for. Giuseppe has grown increasingly disappointed, and feels lonely in this enterprise since his extemporaneous attempts or ‘timid’ actions towards language renewal/revitalization often soon die out of lack of generalized local consensus. Commenting on the Spitta initiative, Rocco from Sternatia, told me,

Luigi from Martano is harsher: “This experiment is odious. Griko is a language to use for poetry, for songs; otherwise it is nothing.” Roberto from Calimera makes a similar point: “Griko is the expression of nostalgia, it is surely not something modern.” Prof. Tommasi echoes them:

Prof. Tommasi has always stated explicitly that he does not foresee for Griko any future as a spoken language, but rather as a testimonianza, as ‘proof,’ of the cultural heritage to leave for posterity in the written form. Interestingly, while compiling the textbook Pos Màtome Griko (How We Learn Griko) that I mentioned above, he actually disagreed more tenaciously on the communicative situations to choose and describe in the various units of the book—among them, going to the airport, to the bank, going to school, etc.—arguing that there was no point in dealing with topics where Griko’s vocabulary lacks linguistic resources such as those above; his position was broadly shared. The creation of neologisms and/or the linguistic recovery of forgotten terms/verbs were not explicitly addressed, in fact, and thus not systematically covered in the book. The agreement reached was that we should use existing texts from the folklore collection of songs, poems, sayings, but also from recent publications or texts. [13]

Certainly it is a praiseworthy experiment; however, they want to write about modern topics, therefore their writing becomes unyielding, elementary and inevitably they must resort to Italian or Salentine. The traditional texts from the past such as songs, proverbs, poems, are highly poetic instead.

I like the idea, but they stretch the language by trying to write about current events; every ten words, five or six are not Griko words. The same goes for the news in Griko on TV: no one could understand anything. Griko was a folk language [lingua popolare]; so, either you use its own words, or you make no sense at all. [12]

The level A1 units for children covered basic and thus relatively uncontested topics such as greetings, the family, the weather, etc., but also physical descriptions of people, food, and leisure activities. Interestingly, as the level of proficiency required increases to B1 and B2, the topics covered increasingly relate to the past: songs of Grecìa Salentina, fairytales, popular beliefs, traditional crafts and customs, traditional recipes, etc. The very content of the units was heavily based on the descriptions of the past; also the more recent texts documented the traditional Griko life, as it were, building on the description of locals’ memories. Indeed, the past was ever present. [14]

The prevailing argument is, in fact, that Griko vocabulary is restricted to covering mainly the domains of the peasant world—and of family—and that this renders the language inadequate for the communicative domains of the ‘present,’ of the contemporary and modern world. For this reason the Spitta initiative receives a mixed reception, and this is also why an early initiative of broadcasting news in Griko on local TV—which goes back to 2005, and to which Prof. Tommasi refers above—was popularly highly criticized. Griko’s linguistic resources are considered instead more apt to be used in songs and poems, so the argument goes, and this is indeed reflected in locals resorting to Griko for performative purposes. This practice, as I show in the next chapter, has been increasing over time.

What emerges from my ethnography is how Griko is largely perceived as ‘a language of the past,’ which while being temporally close, points to a world and an experiential reality that do not exist as remembered despite being described by it. Griko, however, remains in context in that local chronotope; this way it is indexical of ‘that’ inevitable historicity, connecting it with ‘that’ past. When people look back at the past emotionally, with nostalgia, Griko becomes its representation, its expression, as Roberto stated above; it becomes an object of contemplation.

On the contrary, de-contextualizing Griko by ‘bending’ and ‘stretching’ it in order to write (or speak) about contemporary topics is largely considered as fake, even folkloristic—and attempts to this end are often silenced or marginalized. The majority of the locals seem indeed to be more concerned about Griko’s authenticity (however defined) than they are about its ‘death’ as a language of daily communication. Indeed, even when they ‘could’ speak Griko, they often do not; they tend to resist attempts to continue a conversation in the language beyond the ‘usual’ topics, switching to Salentine and/or Italian, and remarking it does not come ‘naturally’ to them—it is out of context, so to speak—or else that ‘that Griko’ is not the same language as the elderly would speak. While locals often metalinguistically comment with regret on Griko’s limitations in expressing the needs of the present, they ultimately resist language change and/or renewal, equating it to ‘decay.’ Similarly, they consider that leaving to posterity—in writing—an incorrect version of Griko would show a lack of respect towards both the language and the people who speak it. Characteristically, Gianni from Sternatia poignantly argued, “It is best to let Griko die with dignity than to humiliate it.” In other words, the prevailing view at present is that Griko should be kept ‘as it is.’

These dynamics, however, extend beyond concerns about language competence, accuracy, purism or compromise; it shows, I argue, how authenticity ultimately builds on locals’ perceptions of morality and aesthetics, which feed into each other. Locals, therefore, may rest on their own memories of the past, as discussed above, directing their preferences and attachments to a specific lexical choice, expression, and pronunciation, and thus linking Griko to a local chronotope. In such instances morality and aesthetics converge with affect. Being socially distributed, locals’ language ideologies may intermingle with projections of a temporally distant but glorious past, yet a past which connects contemporary Southern Italy and Greece; this in turn equally influences language choices and tastes, projecting Griko as a language which enables global connections—as one of the languages of Hellenism in the world. Hence, the moral drive to ‘keep Griko as it is’ translates into ‘purifying’ it aesthetically of Salentine/Italian borrowings, which would not be comprehensible beyond locality and would confine Griko to it.

By debating Griko, locals have certainly endured interest in the language; more to the point, the analysis of these multiple debates shows how they are not about language per se; often framed as debates over what counts as ‘authentic’ Griko, they are rather disputes about competing language ideologies, which are linked to different historicities. They ultimately unravel what I call the cultural temporality of language by revealing locals’ views and perceptions, about the role of Griko in the past-present-future. By celebrating Griko’s internal variation as richness and resisting standardization, by debating linguistic recovery and renewal, by contending the form in which it ought to be transmitted to posterity, locals express their moral alignments to the past as well as their projections to the future, which build on and recursively affect language ideology and practice. Such ideological debates ultimately lead to a power struggle over who holds the ‘knowledge’ to determine what is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ for Griko, and so determine its future—whether mother-tongue speakers, cultori del Griko, or language experts—and what defines it, whether embodied knowledge or philological expertise. This is what I turn to discuss.

From Authenticity to Authority: The Older the Better?

One November night, I was hanging out with Uccio (in his late eighties) and Cosimino (in his mid-seventies), both fluent Griko speakers from Sternatia. We had just attended a Modern Greek class at Chora-Ma in Sternatia. Giorgio was passing by and stopped to say hi. We were chatting in Griko, and I was asking Cosimino and Uccio to clarify the use of the form “we speak Griko.” Mine was a genuine question, as I kept hearing locals using multiple forms so it was a matter of grammar that was not totally clear to me at the time.

Uccio immediately invited Giorgio to answer, and with a hint of irony said, “Eh, Gio! You, how would you say what we are trying to say?” Giorgio replied promptly that the correct form is milùme is Grika. His reply overlapped with Cosimino’s, who instigated the controversy and suggested that ‘maybe’ both milùme to Griko and milùme is Grika are correct. Then Giorgio explained—switching to Salentine—that the correct forms are: milùme Grika and milùme is Grika, clarifying that here Grika is an adverb; milùme to Griko is also correct, but in this case Griko is a noun. His ‘grammatical’ explanation seemed to upset Uccio, who intervened and, addressing Cosimino, said, “We who are without pen, we say it as it comes. But these who have taken up the pen, these who write there …” Giorgio tried to reply, but Uccio interrupted him. After having invited him to answer my question, as he represented the ‘authority’ as a Griko expert/teacher, Uccio did not let him speak, continuously fighting to hold the floor and raising his voice to speak over Giorgio.

The hint of irony with which Uccio invited Giorgio to answer is part of the troubled relationship he seems to have with the authoritative voice of Giorgio as both an educated man and a Griko teacher. Uccio concluded, “Our language, it is not as if there is something written by anyone. But now, these people, now they are writing the grammar” (emphasis in original). Uccio’s remark to Cosimino, “We [who are] without a pen” indicates the authority that elderly people project onto educated people, an authority they feel they lack as the majority of them had limited access to education. Yet the power relation changes totally when it comes to Griko. Uccio had learned Griko as his mother tongue, whereas Giorgio is not perceived as having this same fluency. This is due to his younger age; he simply has not lived that past. Nevertheless, he is highly competent and respected as an expert.

Uccio’s heated reaction has to do with the sudden proliferation of ‘Griko experts’ who are part and parcel of the revival. This has had the unexpected effect of isolating elderly Griko speakers, who became rather skeptical and suspicious toward the newcomers. They feel their own ‘expertise’ is being supplanted by non–mother-tongue speakers. This contextualizes Uccio’s simultaneously defensive and aggressive attitude towards ‘people with a pen.’ He is reclaiming his legitimate authority over Griko, as it were: Griko is a language of oral tradition and fluent speakers use it “as it comes” (organically). Moreover, speaking Griko is not a reflexive practice. It is linked to speakers’ experiential past and present; they therefore do not need to look for rules. By contrast, “ they ” look for rules—meaning language experts, grammar writers, Griko scholars, and me! He twice stresses the word ‘now,’ nodding to the ongoing revival. [15]

Elderly Griko speakers in fact rarely engage in these folk linguistic exercises unless they are prompted by ‘semi-speakers’ or researchers. Adriana bluntly made the same point: “I think in Griko, all these experts of Griko do not! They need to think about what they are saying. A language is really yours only if you think and dream in it” (emphasis in original), she concluded, emphatically reclaiming her own legitimacy as a mother-tongue speaker, and thus her authority over Griko, challenging the authority of those who do not ‘think’ and ‘dream’ in the language). Comments such as this insist on the “moral significance of ‘mother tongue’ as the first and, therefore real language of a speaker” (Woolard 1998:18, emphasis in original). This ideology leads to a constant monitoring of how people speak Griko, which in turns disinclines less fluent speakers—and potential new speakers for that matter—from using the language and causes them to engage in a continuous self-monitoring at the risk of failing to meet expectations.

It is indeed true that Griko speakers and local Griko scholars often question the competence of Griko teachers, some more openly than others; I have heard them do so repeatedly. Among the recurrent debates, they refer to the quality of the training offered to Griko teachers. There is a strong consensus that the Master’s program was a failure, since several subjects were being taught (musicology, archeology, history, popular traditions, Modern Greek, Greek history, and tourism), but lessons specifically dedicated to the Griko language were insufficient to train the new Griko teachers. [16] Giorgio from Sternatia was very clear about his views; he argued that those who attended the Masters, but who did not already know Griko, certainly did not learn it from the course. Tonia from Zollino, who attended it, pointed out that most of those who can speak Griko could not attend the Masters, as they do not hold a university degree; they are therefore not qualified to teach it. Meanwhile, those with the appropriate qualifications lack competence in the language, and so on.

However, generalizations are misleading. When I interviewed Griko teachers, their assessment of their own linguistic competence varied considerably from case to case: those who are older have had more exposure to Griko than the younger teachers; some of them also know Modern Greek or Ancient Greek, some of them do not; some are more passionate about Griko than others; and some of them have lost their zeal for Griko in the process of trying to teach it. Having undertaken participant observation during Griko classes, I can attest to the goodwill of the teachers and the effort they put into teaching. As a result, I found the criticisms rather harsh; these teachers work in the face of many challenges locally, and they are constantly vulnerable to annual funding issues at the national and regional level, which is dependent on their total number of teaching hours per year (see Chapter 4).

From their perspective, Griko teachers feel they are looked upon as second-class teachers, which translates also into their underpayment compared to ‘fully appointed’ teachers. Indeed, according to Article 4 of National Law 482, the use of the minority language is envisaged alongside the use of Italian: this means that Griko teachers are expected to teach only in the presence of a ‘fully appointed’ teacher, who may or may not come from a Griko-speaking village (most of the time not). This renders their task even more difficult. When, in the early 2000s, Griko experts were trained to teach the language they were young locals in their late 20s—the new hope for the future of Griko, as it were. Yet, they often feel their linguistic competence being scrutinized and the relevance of their role being questioned, and so complain about the general resistance to specialist control. In another conversation Giorgio let his dissatisfaction slip when he told me, “Everyone feels entitled to judge. When we talk about medicine, the experts are the doctors, right? If we talk about veterinary medicine, the experts are the vets, right? When it comes to Griko, however, everyone sees himself as a ‘Griko expert.’ Everyone is an ‘expert’!”

Who Knows What for Whom? Power Struggles over Griko

It all started with a rather simple question. Michele, born in 1975, and, unusually for his age, a mother-tongue Griko speaker from Sternatia, asked the members of the WhatsApp group I glossa grika (the Griko language) I had set up, “How do we say ‘river’ in Griko?” The group is composed of speakers and/or activists, as well as Griko scholars and aficionados; the first to reply was Paolo, a Griko speaker and activist, who suggested that the word might have been ‘lost’—probably due to the scarcity of water in the area—and proposed using potàmi, incidentally the MG word for river; he justified his choice by saying that we keep the root in the verb ‘to pot’ (to potìsi).

Tonia asked about the Calabrian Greek word for “fiume” (potamò). Alfredo supported Paolo’s choice, and referenced the Italian word hippopotamo, which would make it possible to avoid adapting the Salentine/Italian fiùmo. This is when Raffaele, another Griko teacher, texted at length, pointing out firmly that fiùmo is the Griko word to use because it was attested in Vito Domenico Palumbo’s tales, and also by the linguist Morosi, and there was no need ‘to go to the trouble’ (Italian: scomodare) of using Calabrian Greek, or building off ‘hippopotamus’; he added, “Let’s keep the language the way it has been transmitted to us—by the way there are still elderly speakers who speak correctly and we can ask them how they say things without ‘turning everything upside down’ (Italian: stravolgere). We see here again the moral imperative to ‘keep’ Griko as it has been transmitted, and to ‘respect’ those who still speak it.

The WhatsApp debate went on, and others intervened with varying views: “A language is not something to fix and transmit, but a living organism which changes over time, so if Griko speakers find it useful to add a neologism, I do not see anything strange about it. I’d go for potami,” Silvio—a speaker and cultore del Griko —added, trying to divert from the general tendency to keep Griko ‘unchanged.’ The chat was abruptly interrupted by this message sent by Raffaele: “Everyone is free to do all linguistic recoveries he pleases; in any case the elderly, who are the true speakers, will keep speaking like they have always done, ignoring these recoveries and neologisms; by the way these are matters for linguists.”

As is often the case, the Griko teacher’s last message ‘silenced’ the proposal for language change/renewal, in this instance by pointing out that generating neologisms or ‘recovering’ forgotten terms are not a matter of individual will; rather, there is the element of whether other Griko speakers accept such changes—and elderly speakers, Raffaele argued, would not. Indeed, languages evolve over time when they are widely used, and when changes are embraced by others. When they are not, the outcome is an idiolect, a personalized and intimate vocabulary that allows communication only among those who share it, but that excludes others. Ironically Griko’s internal richness is partly due to the fact that it ‘survived’ through idiolects, but now that it is no longer a language predominately used to exchange information, any change to it is instead matter of representation, which creates tensions among speakers.

Significantly, the Griko teacher’s last message also reveals, one again, how smooth the shift is from defining the ‘authentic’ Griko word to defining who can claim authority over the language. He first ascribes it to past speakers—(“ Fiùmo is the Griko word to use because it was attested in Vito Domenico Palumbo’s tales, and also by the linguist Morosi” in nineteenth-century sources); this reveals a language ideology that privileges “the authoritative word” of distant ancestors (Bakhtin 1981) whose influence is still felt. Then he shifts authority over Griko to present-day elderly speakers, who are true speakers (my emphasis) because it was their mother tongue. Here competence is largely associated with age (“There are still elderly speakers who speak correctly and we can ask them”). His last message, however, also refers to linguists, as operations/interventions such as linguistic recovery and the formation of neologisms fall under philological/linguistic expertise.

What we see at play here is the semiotic process of fractal recursivity, defined by Judith Irvine and Susan Gal as “the projection of an opposition, salient at some level of relationship, onto some other level” (2000:37). We have seen how the ideologically constructed opposition at the temporal level—pre-contact past/recent past—is projected onto the linguistic level, becoming an opposition along the purism and compromise continuum. This opposition is then further projected onto the social level, onto community members shifting from Griko speakers to experts, present and past. One of the characteristics of fractal recursivity is that this opposition can be reproduced repeatedly and be projected onto narrower and broader comparisons (Gal 2005).

By debating what authentic Griko stands for—a debate which intermingles issues of morality and aesthetics, as discussed above—locals simultaneously define who can and cannot claim authority over it; this ultimately highlights the power struggles intensified by the current revival. Indeed, at times embodied knowledge prevails over philological expertise in the definition of authority; at times it does not. Speakers of the past may be—and usually are—perceived as more authoritative than today’s speakers, while today’s speakers tend to remain more authoritative than language experts. In the meantime, experts, cultori del Griko, and activists who have long engaged with the language may claim more authority over Griko than those who have approached it more recently, and so forth. This process continuously creates separations, “in a series of interconnected layers that are necessarily embedded in the original construction, which is what makes it recursive” (Razfar 2012:66).

What is revealing is how all these activists and cultori del Griko motivate their engagement with Griko by referring to the duty to preserve it; they express a sense of moral responsibility towards the language itself but articulate it in different ways: to systematically record and document Griko, to transmit it in writing, to use as a performative resource—as we will see in the next chapter—and only a minority among the minority, to promote its use as a spoken language for daily use. This dynamic at times produces a bond among those who share the same language ideologies and visions of Griko’s past and future; such ‘intergroup intimacies’ then become the humus for social encounters, for building interpersonal relations, and for creating synergies and collaborations among activists, speakers, and cultori del Griko. The opposite dynamic, however, equally takes place, when divergent language ideologies serve to produce not only interpersonal but also ‘intragroup estrangements’; these generate tensions and lead activists and cultori del Griko to carry out independent activities and Griko courses that further fracture the languagescape. Even those who agree to promote Griko as a spoken language end up disagreeing on whether and how to implement it; those who agree to transmit it in writing may not—and often do not—agree on how to transcribe it and so on, while they tend to complain when their positions and proposals are not shared or followed. Many among the Griko speakers, activists and scholars mentioned above have sometimes fallen out with one another at different moments in time, because of their different positions on issues such as orthographic transcription and linguistic renewal and/or the future envisaged for Griko.

Significantly, what is morally right and emotionally sound for Griko is not only fueled by their concerns about the fate of Griko, but is also linked to their personal investments in Griko, as each of them claim in the process their competence, expertise, and long-lasting engagement with Griko (in other words, their own authority over Griko). Cultori del Griko and activists who have engaged with Griko for decades now enjoy the prestige associated with knowing Griko and the social recognition and visibility achieved as experts in the field, both in Grecìa Salentina and in Greece, where they equally cultivate relationships; they may consequently fear being overshadowed, so to speak, by those who only recently ‘joined in.’ This dynamic once again highlights a growing sense of uneasiness about losing control over their own spaces of action. [17]

Following the argument by Michel Foucault, such power struggles exemplify “a politics of knowledge” and the relations of power, which pass via knowledge (1982). In a vibrant metalinguistic community such as this, where competence in and knowledge of Griko are supposedly diffuse—where ‘everyone is an expert’ of Griko—the struggle starts from the need to define and assert the kind of knowledge that confirms authority and confers power; this means to establish a hierarchy which elevates one kind of knowledge/expertise over another. This is, however, constantly contested, negotiated, and only provisionally achieved; it keeps fluctuating from experiential knowledge and embodied linguistic competence (mother-tongue speakers) to philological expertise (language experts and scholars of Griko), passing though active engagement (Griko activists). This ultimately leads to a struggle over who gets access to the material, as well as symbolic means of re-presentation—a dynamic which expands to the management of cultural heritage more broadly, as I discussed in the previous chapter.

My ethnography has, however, revealed not only how these multiple social actors constantly and simultaneously attempt to validate their own knowledge and exert authority, but crucially their need and desire to draw recognition from others and over others. This is ultimately what confers social prestige and hence power at the local level, allowing those who hold it to proclaim what is ‘right or wrong’ for Griko—which orthographic conventions will prevail, whether Griko eventually will or will not be ‘updated’ to express modern needs, and so on—ultimately the right to present and re-present Griko, and to determine the route to its future. Indeed, one of the salient traits defining a relationship of power is that it is “a mode of action which does not act directly and immediately on others. Instead, it acts upon their actions: an action upon an action, on existing actions or on those which may arise in the present or the future” (Foucault 1982:789).

All the language ideological debates discussed in this chapter are, however, deeply embedded in the demands of the present. Processes of minority languages standardization, renewal, and/or revitalization remain entangled in globally shared political and economic dynamics. This ethnography, on the other hand, shows that ultimately, neither can such processes be disentangled from the historical specificities of each minority language, from the prevailing local sensibilities of its speakers, or from the social dynamics they generate on the ground. The current languagescape ultimately shows that the role that locals envisage for Griko on its path to the future remains vigorously contested. Yet, Griko has re-entered the experiential reality of locals in multiple forms that go beyond such debates, and beyond the ‘vitality’ of Griko as a medium of daily communication, as I move to discuss in the next chapter.

Footnotes

[ back ] 1. See McDonald 1989 and Timm 2001, who highlight these issues for the case of Breton, as well as Roseman 1995 and Jaffe 1999 for the case of Corsican.