-

Gregory Nagy, Comparative Studies in Greek and Indic Meter

Foreword

Acknowledgments

Checklist of Greek (G) and Indic (I) Metrical Terminology

Symbols

Abbreviations of Editions

Introduction

Part I. κλέοc ἄφθιτον and Greek Meter

1. The Common Heritage of Greek and Indic Meter: A Survey 2. Internal Expansion 3. On the Origins of Dactylic Hexameter 4. The Metrical Context of κλέοc ἄφθιτον in Epic and Lyric 5. The Wedding of Hektor and Andromache: Epic Contacts in Sappho 44LP 6. Formula and Meter: A Summary Part II. śráva(s) ákṣitam and Indic Meter

7. The Metrical Context of Rig-Vedic śráva(s) ákṣitam and ákṣiti śrávas 8. An Inquiry into the Origins of Indic Trimeter 9. The Distribution of Rig-Vedic śrávas: An Intensive Correlation of Phraseology with Meter Epilogue: The Hidden Meaning of κλέοc ἄφθιτον and śráva(s) ákṣitam Appendix A. μήδεα and ἄφθιτα μήδεα εἰδώc Appendix B. Dovetailing: Speculations on Mechanics and Origins Selected Bibliography

9. The Distribution of Rig-Vedic śrávas: An Intensive Correlation of Phraseology with Meter

The usage of a word like śrávas in the Rig-Veda is subject to manifold constraints in matters of positioning and associations with other words. It now becomes imperative to examine such constraints in relation to meter and metrical origins. Beyond the immediate interest, the great advantage in such an examination is that we may discover the matrix of the poetic expression śráva(s) ákṣitam.

As an appropriate starting-point, let us consider the constraints on śrávas plus ákṣitam/ákṣiti. In all four Rig-Vedic instances where śrávas occurs with these epithets ákṣitam and ákṣiti, the verb dhā- also occurs, in the middle voice (meaning ‘acquire’):

dhatte / dhatte / dádhāno / dhehi

(RV 1.40.4 / 8.103.5 / 9.66.7 / 1.9.7)

In fact, from among the 87 attestations of śrávas (nominative/accusative singular) in the Rig-Veda, 24 are in collocation with the verb dhā-, by my count. When śrávas is in certain positional slots, such as in 9 10 of 11 (that is, the ninth and tenth syllables of hendecasyllabic verses), there is a 100% co-occurrence of śrávas with dhā-. These slots 9 10 of 11 reveal still another interesting constraint. Whenever the imperative of dhā-, dhehi, occurs with śrávas, the word asmé ‘to us’ is also {191|192} present (RV 1.9.7, 1.9.8, 1.43.7, 1.44.2, 1.79.4, 4.17.20, 8.65.9); only once is it missing, but here too we find an appropriate substitute, the enclitic nas, likewise meaning ‘to us’, which is a syntactic variant of the non-enclitic asmé ‘to us’:

(RV 1.40.4 / 8.103.5 / 9.66.7 / 1.9.7)

urugāyám ádhi dhehi śrávo naḥ (RV 6.65.6)

Significantly, the position of nas in slot 11 of this 11-syllable Triṣṭubh verse is elsewhere in Triṣṭubh verses occupied exclusively by dhā- wherever this verb is in collocation with śrávas in syllables 9 10:

sá no marúdbhir vṛṣabha śrávo dhā(s) (RV 1.171.5)

sá vā́jaṃ darṣi sá ihá śrávo dhāḥ (RV 10.69.3)

sá vā́jaṃ darṣi sá ihá śrávo dhāḥ (RV 10.69.3)

There is another pertinent attestation of dhā-, in the Dvipadā Virāj versification of RV 7.34. In this connection, we must note that the second of the two 5-syllable units in the 10-syllable Dvipadā Virāj line, ⏓ – ⏑ – ⏓#, is identical to the last 5 syllables of a Triṣṭubh line. [1] Because of this metrical identity, a Dvipadā Virāj decasyllable often interchanges in the same stanzas with Triṣṭubh hendecasyllables, and RV 7.34 is a hymn noted for this phenomenon. [2] Such an instance of metrical interchangeability {192|193} suggests genetic affinity between Dvipadā Virāj and Triṣṭubh verses. Arnold in fact proposes to derive the former from the latter on the basis of metrical pattern: the 6th syllable is being systematically deleted from an 11-syllable verse when the caesura comes after the 5th syllable. [3] We are now in a position to corroborate this proposed structural connection by showing that interchangeability between Dvipadā Virāj and Triṣṭubh is not just metrical but also phraseological. The case in point is

utá na eṣú||nṛ́ṣu śrávo dhuḥ (Dvipadā Virāj, RV 7.34.18)

If indeed the Dvipadā Virāj verse is metrically 1 2 3 4 5||7 8 9 10 11 (with no 6), then the 9 10 11 = śrávo dhuḥ here matches the 9 10 11 = śrávo dhā(s) of the Triṣṭubh verses which we have just surveyed, RV 1.171.5 and 10.69.3. As for an instance of such interchangeability even in the openings of decasyllables and hendecasyllables, I cite abhí śrávas in syllables 1 2 3 4 of RV 1.61.10 (decasyllabic) and of RV 6.37.3 (hendecasyllabic).The collocations of ákṣiti/ákṣitam with śrávas with dhā- with asmé/nas in the Rig-Veda are an obvious indication of traditional and archaic phraseology. There are also other such distributional vestiges triggered by śrávas, as we see for example in the functional restriction {193|194} of every co-occurring locative plural to the god/man thematic axis: [4]

1.102.7 kṛṣṭíṣu (śrávas)

‘peoples’

1.110.5 ámartyeṣu (śrávas)

‘immortals’

3.53.15 (śrávo) devéṣu

‘gods’

3.53.16 (śrávaḥ) pā́ñcajanāsu kṛṣṭíṣu

‘peoples of the five races’

4.31.15 (śrávo) devéṣu

‘gods’

5.7.9 (śrávas) … mártyeṣu

‘mortals’

7.34.18 nṛ́ṣu (śrávas)

‘men’

8.65.12 (śrávo) devéṣu

‘gods’

9.98.8 sūríṣu (śrávas)

‘patrons [of the sacrifice]’

10.62.7 (śrávo) devéṣu

‘gods’

10.93.10 vīréṣu … (śrávas)

‘men’

10.155.5 devéṣu … (śrávas)

‘gods’

‘peoples’

1.110.5 ámartyeṣu (śrávas)

‘immortals’

3.53.15 (śrávo) devéṣu

‘gods’

3.53.16 (śrávaḥ) pā́ñcajanāsu kṛṣṭíṣu

‘peoples of the five races’

4.31.15 (śrávo) devéṣu

‘gods’

5.7.9 (śrávas) … mártyeṣu

‘mortals’

7.34.18 nṛ́ṣu (śrávas)

‘men’

8.65.12 (śrávo) devéṣu

‘gods’

9.98.8 sūríṣu (śrávas)

‘patrons [of the sacrifice]’

10.62.7 (śrávo) devéṣu

‘gods’

10.93.10 vīréṣu … (śrávas)

‘men’

10.155.5 devéṣu … (śrávas)

‘gods’

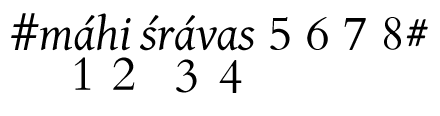

Thus, the presence of these and still other such inherited elements in the Rig-Veda should {194|195} come as little surprise by now. Yet there does emerge a remarkable new factor: the distribution of traditional phraseology can be correlated with meter, as we have already seen in the case of śrávas vs. dhā- in decasyllabic and hendecasyllabic meters. Further examples are now in order, and it seems appropriate to begin with another instance where one meter is overtly derivable in terms of another. The case in point is the Uṣṇih-B stanza, where two 8-syllable verses are followed by a 12-syllable verse that consists of an 8-syllable and a 4-syllable segment; this 4-syllable segment is in turn basically identical in meter to the closing of the 8-syllable verse. [5] Now in the Uṣṇih-B stanza of RV 1.79.4, this 4-syllable segment is occupied by the phrase máhi śrávas (cognate of Greek μέγα κλέοc). This same phrase occurs 6 times in the closing, that is, in syllables 5 6 7 8 of 8-syllable verses: RV 5.18.5, 8.55.5, 9.4.1, 9.9.9, 9.61.10, 9.100.8. In fact, the only other attested position of máhi śrávas in Rig-Vedic 8-syllable verse is within the confines of the other functional 4-syllable segment, that is, in the opening 1 2 3 4: RV 1.43.7 (only once!). Thus the metrically established opening vs. closing segmentation of 1 2 3 4 vs. 5 6 7 8 is matched by the phraseological distribution of the phrase máhi śrávas, in that it occupies only 1 2 3 4 or 5 6 7 8, to the exclusion of 2 3 4 5, 3 4 5 6, 4 5 6 7. {195|196} In regular 12-syllable Jagatī verse as well, máhi śrávas occurs only in the first four (RV 6.70.5) or in the last four syllables (RV 1.160.5, 9.80.2) of the same verse.

Such phraseological evidence as the distribution of máhi śrávas in syllables 1 2 3 4 and 9 10 11 12 of dodecasyllables is an indication of 4 + 4 + 4 (4 + 4 + 3) segmentation in the trimeter, a phenomenon which is diachronically reconstructable but synchronically latent in the metrical evidence. These considerations lead me to a hypothesis which may be formulated as follows:

While traditional meter and traditional phraseology are formally correlate in origin, their evolution may diverge. At the start, traditional phraseology sets and then regulates quantitative patterns (= meter) by force of precedent, but the resulting fixed meter evolves dynamics of its own and becomes the regulator of any incoming nontraditional phraseology. By becoming a structure in its own right, meter may also develop independently of traditional phraseology. Thus it could even happen that newly-developed laws of meter may obliterate aspects of the very phraseology that had originally engendered them, if these aspects no longer match the meter. We will now test this hypothesis further by surveying all the phraseological and metrical contexts of śrávas in the Rig-Veda. {196|197}

Table 1. Rig-Vedic Occurrences of śrávas in the Nominative/Accusative Singular

| 1.9.7 | 5-6 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #asmé pṛthú śrávo bṛhát# #viśvā́yur dhehy ákṣitam# |

| 1.9.8 | 5-6 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #asmé dhehi śrávo bṛhád#dyumnáṃ ... |

| 1.40.4 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Satobṛhatī) | #sá dhatte ákṣiti śrávaḥ# |

| 1.43.7 | 3-4 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #...dhehi...# #máhi śrávas tuvinṛmṇám# |

| 1.44.2 | 5-6 | of | 8 | (Satobṛhatī) | #asmé dhehi śrávo bṛhát# |

| 1.51.10 | 10-12 | of | 12 | (Jagatī) | #ā́ púryamāṇam avahann abhí śrávaḥ# |

| 1.61.10 | 3-4 | of | 10 | (Arnold, VM 240f) | #abhí śrávo dāváne sácetāḥ# |

| 1.73.7 | 3-4 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #diví śrávo dadhire yajñíyāsaḥ# |

| 1.73.10 | 3-4 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #ádhi śrávo devábhaktam dádhānāḥ# |

| 1.79.4 | 3-4 | of | 4 | (Uṣṇih) | #asmé dhehi jātavedo#máhi śrávaḥ# |

| 1.102.2 | 3-4 | of | 12 | (Jagatī) | #asyá śrávo nadyàḥ saptá bibhrati# |

| 1.102.7 | 11-12 | of | 12 | (Jagatī) | #út sahásrād ririce kṛṣṭíṣu śrávaḥ# |

| 1.110.5 | 6-7 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #ámartyeṣu śráva icchámānāḥ# |

| 1.117.8 | 6-7 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #yán nārṣadā́ya śrávo adhyádhattam# |

| 1.126.1 | 6-7 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #atúrto rā́jā śráva icchámānaḥ# |

| 1.126.2 | 3-4 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #diví śrávo 'járam ā́ tatāna# {197|198} |

| 1.126.5 | 5-6 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #ánasvantaḥ śráva áiṣanta pajrā́ḥ# |

| 1.160.5 | 11-12 | of | 12 | (Jagatī) | #té no gṛṇāné mahinī máhi śrávaḥ# |

| 1.165.12 | 5-6 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #ánedyaḥ śráva éṣo dádhānāḥ# |

| 1.171.5 | 9-10 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #sá no marúdbhir vṛṣabha śrávo dhā# |

| 3.37.10 | 5-6 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #ágann indra śrávo bṛhád# #dyumnáṃ dadhiṣva duṣṭáram# |

| 3.53.15 | 1-2 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #...tatāna# #śrávo devéṣv amṛ́tam ajuryám# |

| 3.53.16 | 3-4 | of | 12 | (irregular) | #ádhi śrávaḥ pā́ñcajanāsu kṛṣṭíṣu# |

| 4.17.20 | 3-4 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #tváṃ rā́jā janúṣāṃ dhehy asmé# #ádhi śrávo mā́hinaṃ yáj jaritré# |

| 4.26.5 | 3-4 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #utá śrávo vivide śyenó átra# |

| 4.31.15 | 1-2 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #śrávo devéṣu sūrya# |

| 4.36.9 | 3-4 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #ihá śrávo vīrávat takṣatā naḥ# |

| 4.38.5 | 1-2 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #śrávaś cā́cchā paśumác ca yūthám# |

| 5.7.9 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Anuṣṭubh) | #áiṣu dyumnám utá śráva# #ā́ cittám mártyeṣu dhāḥ# |

| 5.16.4 | 3-4 | of | 8 | (Anuṣṭubh) | #pári śrávo babhūvatuḥ# {198|199} |

| 5.18.5 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Pag̣kti) | #dyumád agne máhi śrávo# #bṛhát kṛdhi maghónāṃ# #nṛvád amṛta nṛṇā́m# |

| 5.35.8 | 3-4 | of | 8 | (Anuṣṭubh) | #diví śrávo dadhīmahi# |

| 5.52.1 | 1-2 | of | 8 | (Anuṣṭubh) | #śrávo mádanti yajñíyāḥ# |

| 5.86.6 | 5-6 | of | 8 | (Anuṣṭubh) | #tā́ sūríṣu śrávo bṛhád# |

| 6.1.4 | 5-6 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #śravasyávaḥ śráva āpann ámṛktam# |

| 6.2.1 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Anuṣṭubh) | #tváṃ vicarṣaṇe śrávo# |

| 6.37.3 | 3-4 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #abhí śráva ṛ́jyanto vaheyur# |

| 6.46.5 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Bṛhatī) | #ójiṣṭham pápuri śrávaḥ# |

| 6.48.12 | 1-2 | of | 8 | (Satobṛhatī) | #śrávó 'mṛtyu dhúkṣata# |

| 6.58.3 | 6-7 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #kā́mena kṛta śráva icchámānaḥ# |

| 6.65.3 | 1-2 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #śrávo vā́jam íṣam úrjaṃ váhantīr# |

| 6.65.6 | 9-10 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #urugāyám ádhi dhehi śrávo naḥ# |

| 6.70.5 | 3-4 | of | 12 | (Jagatī) | #dádhāne...# #máhi śrávo vā́jam asmé suvī́ryam# |

| 7.5.8 | 3-4 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #pṛthú śrávo dāśúṣe mártyāya |

| 7.18.24 | 3-4 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #yásya śrávo ródasī antár urvī́# |

| 7.34.18 | 3-4 | of | 5 | (Dvipadā) | #utá na eṣú#nṛ́ṣu śrávo dhuḥ# {199|200} |

| 7.81.6 | 1-2 | of | 12 | (Satobṛhatī) | #śrávaḥ sūríbhyo amṛ́taṃ vasutvanáṃ# |

| 8.9.17 | 5-6 | of | 8 | (Anuṣṭubh) | #prá mádāya śrávo bṛhát# |

| 8.13.12 | 1-2 | of | 12 | (Uṣṇih) | #śrávaḥ sūríbhyo amṛ́taṃ vasutvanám# |

| 8.15.8 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Uṣṇih) | #pṛthivī́ vardhati śrávaḥ# |

| 8.31.7 | 1-2 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #śrávo bṛhád vivāsataḥ# |

| 8.46.24 | 10-11 | of | 11 | (irregular) | #abhūd várṣiṣṭham akṛta śrávaḥ# |

| 8.55.5 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Anuṣṭubh) | #ā́nūnasya máhi śrávaḥ# |

| 8.65.9 | 5-6 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #asmé dhehi śrávo bṛhát# |

| 8.65.12 | 1-2 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #śrávo devéṣv akrata# |

| 8.74.9 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #...bṛhád#úpopa śrávasi śrávaḥ# |

| 8.80.5 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #upamáṃ vājayú śrávaḥ# |

| 8.89.4 | 1-2 | of | 8 | (Satobṛhatī) | #śrávaś cit te as ad bṛhát# |

| 8.103.5 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Satobṛhatī) | #...vā́jam...#sá dhatte ákṣiti śrávaḥ# |

| 9.1.4 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #abhí vā́jam utá śrávaḥ# |

| 9.4.1 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #pávamāna máhi śrávaḥ# |

| 9.6.3 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #abhí vā́jam utá śrávaḥ# |

| 9.7.9 | 1-2 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #śrávo vásūni sáṃ jitam# |

| 9.9.9 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #pávamāna máhi śrávo# {200|201} |

| 9.20.3 | 5-6 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #sá naḥ soma śrávo vidaḥ# |

| 9.32.6 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #saním medhā́m utá śrávaḥ# |

| 9.44.6 | 5-6 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #vā́jaṃ jeṣi śrávo bṛhát# |

| 9.51.5 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #abhí vā́jam utá śrávaḥ# |

| 9.61.10 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #ugráṃ śárma máhi śrávaḥ# |

| 9.63.12 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #abhí vā́jam utá śrávaḥ# |

| 9.66.7 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #dádhāno ákṣiti śrávaḥ# |

| 9.80.2 | 11-12 | of | 12 | (Jagatī) | #maghónām ā́yuḥ pratirán máhi śráva# |

| 9.83.5 | 9-10 | of | 12 | (Jagatī) | #...vā́jam...# #sahásrabhṛṣṭir jayasi śrávo bṛhát# |

| 9.86.40 | 9-10 | of | 12 | (Jagatī) | #...vā́jam...# #sahásrabhṛṣṭir jayati śrávo bṛhát# |

| 9.98.8 | 5-6 | of | 8 | (Anuṣṭubh) | #yáḥ sūríṣu śrávo bṛhád#dadhé... |

| 9.100.8 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Anuṣṭubh) | #pávamāna máhi śrávas# |

| 10.27.21 | 1-2 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #śráva íd enā́ paró anyád asti# |

| 10.28.12 | 3-4 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #diví śrávo dadhiṣe nā́ma vīráḥ# |

| 10.50.1 | 1-2 | of | 12 | (Jagatī) | #...máhi# #śrávo nṛmṇáṃ ca ródasī saparyátaḥ# |

| 10.62.7 | 1-2 | of | 8 | (Satobṛhatī) | #śrávo devéṣv akrata# {201|202} |

| 10.69.3 | 9-10 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #sá vā́jaṃ darṣi sá ihá śrávo dhāḥ# |

| 10.92.10 | 11-12 | of | 12 | (Jagatī) | #té hí prajā́yā ábharanta ví śrávo# |

| 10.93.10 | 11-12 | of | 12 | (12/12/8/8) | #asmé vīréṣu viśvácarṣaṇi śrávaḥ# |

| 10.102.4 | 6-7 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #prá muṣkábhāraḥ śráva icchámāno# #'jirám... |

| 10.131.3 | 3-4 | of | 12 | (Triṣṭubh) | #nótá śrávo vivide saṃgaméṣu# |

| 10.140.1 | 5-6 | of | 8 | (8/12/12/8) (cf. Arnold, VM 236) | #ágne táva śrávo váyo#máhi... |

| 10.155.5 | 7-8 | of | 8 | (Anuṣṭubh) | #devéṣv akrata śrávaḥ# {202|203} |

Table 2. Rig-Vedic Occurrences of śrávas in Cases Other Than the Nominative/Accusative Singular

| 1.11.7 | 1-2-3 | of | 8 | (Anuṣṭubh) | #śrávāṃsy út tira# |

| 1.31.7 | 6-7-8 | of | 12 | (Jagatī) | #mártaṃ dadhāsi śrávase divé-dive# |

| 1.34.5 | 9-10-11 | of | 12 | (Jagatī) | #tríḥ saubhagatváṃ trír utá śrávāṃsi nas# |

| 1.57.3 | 5-6-7 | of | 12 | (Jagatī) | #yásya dhā́ma śrávase nā́mendriyám# |

| 1.73.5 | 6-7-8 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #bhāgáṃ devéṣu śrávase dádhānāḥ# |

| 1.91.18 | 3-4-5 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #diví śrávāṃsy uttamā́ni dhiṣva# |

| 1.92.8 | 5-6-7 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #sudáṃsasā śrávasā yā́ vibhā́si# |

| 1.95.11 | 6-7-8 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #revát pāvaka śrávase ví bhāhi# |

| 1.103.4 | 5-6-7 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #yád dha sūnúḥ śrávase nā́ma dadhé# |

| 1.113.6 | 5-6-7 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #kṣatrā́ya tvaṃ śrávase tvam mahīyā́# |

| 1.121.14 | 5-6-7 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #iṣé yandhi śrávase sūnṛ́tāyai# |

| 1.134.3 | 1-2-3 | of | 8 | (Atyaṣṭi) | #śrávase vāsayoṣásaḥ# |

| 1.149.2 | 1-2-3 | of | 11 | (Virāj) | #śrávobhir ásti jīvápītasargaḥ# |

| 1.156.2 | 3-4-5 | of | 11 | (Jagatī) | #séd u śrávobhir yújyaṃ cid abhy àsat# |

| 3.1.16 | 5-6-7 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #surétasā śrávasā túñjamānā# |

| 3.19.5 | 3-4-5 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #ádhi śrávāṃsi dhehi tanúsu# {203|204} |

| 3.30.5 | 9-10-11 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #utā́bhaye puruhūta śrávobhir# |

| 3.37.7 | 5-6-7 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #pṛtsutúrṣu śrávassu ca# |

| 3.54.22 | 9-10-11 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #asmadryàk sám mimīhi śrávāṃsi# |

| 3.59.7 | 3-4-5 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #abhí śrávobhiḥ pṛthivī́m# |

| 4.41.9 | 5-6-7 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #raghvī́r iva śrávaso bhíkṣamāṇāḥ# |

| 5.4.2 | 9-10-11 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #asmadryàk sám mimīhi śrávāṃsi# |

| 5.18.4 | 1-2-3 | of | 8 | (Anuṣṭubh) | #śrávāṃsi dadhire pári# |

| 5.61.11 | 3-4-5 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #átra śrávāṃsi dadhire# |

| 6.1.11 | 1-2-3 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #śrávobhiś ca śravasyàs tárutraḥ# |

| 6.5.5 | 6-7-8 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #rāyā́ dyumnéna śrávasā ví bhāti# |

| 6.10.3 | 5-6-7 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #pīpā́ya sá śrávasā mártyeṣu# |

| 6.10.5 | 5-6-7 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #yé rā́dhasā śrávasā cā́ty anyā́n# |

| 6.17.14 | 6-7-8 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #sá no vā́jāya śrávasa iṣé ca# |

| 6.19.3 | 9-10-11 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #asmadryàk sám mimīhi śrávāṃsi# |

| 7.16.10 | 4-5-6 | of | 8 | (Satobṛhatī) | #kā́mena śrávaso maháḥ# |

| 7.18.23 | 6-7-8 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #tokáṃ tokā́ya śrávase vahanti# |

| 7.79.3 | 9-10-11 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #ájījanat suvitā́ya śrávāṃsi# |

| 7.90.7 | 5-6-7 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #árvanto ná śrávaso bhíkṣamāṇā# {204|205} |

| 8.5.32 | 6-7-8 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #ā́ no dyumnáir ā́ śrávobhir# |

| 8.6.48 | 1-2-3 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #śrávasā yā́dvaṃ jánam# |

| 8.70.9 | 4-5-6 | of | 8 | (Bṛhatī) | #úd indra śrávase mahé# |

| 8.74.9 | 4-5-6 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #úpopa śrávasi śrávaḥ# |

| 8.74.10 | 3-4-5 | of | 8 | (Anuṣṭubh) | #yásya śrávāṃsi túrvatha# |

| 8.99.2 | 3-4-5 | of | 12 | (Satobṛhatī) | #táva śrávāṃsi upamā́ny ukthyā\# |

| 8.101.12 | 5-6-7 | of | 12 | (Satobṛhatī) | #báṭ sūrya śrávasā mahā́n asi# |

| 9.32.1 | 1-2-3 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #śrávase no maghónaḥ# |

| 9.62.22 | 4-5-6 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #gṛṇānā́ḥ śrávase mahé# |

| 9.63.1 | 3-4-5 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #asmé śrávāṃsi dhāraya# |

| 9.67.5 | 2-3-4 | of | 8 | (Gāyatrī) | #ví śrávāṃsi ví sáubhagā# |

| 9.70.2 | 6-7-8 | of | 12 | (Jagatī) | #yádī devásya śrávasā sádo vidúḥ# |

| 9.80.3 | 6-7-8 | of | 12 | (Jagatī) | #úrjaṃ vásānaḥ śrávase sumaGgálaḥ# |

| 9.87.5 | 9-10-11 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #mahé vā́jāyāmṛ́tāya śrávāṃsi# |

| 9.97.25 | 5-6-7 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #árvāw iva śrávase sātím ácchā# |

| 9.108.4 | 3-4-5 | of | 8 | (8/12/12/8) | #yéna śrávāṃsy ānasúḥ# |

| 9.110.5 | 6-7-8 | of | 12 | (ŪrdhvaBṛhatī) | #abhy-àbhi hí śrávasā tatárdithā# |

| 9.110.7 | 6-7-8 | of | 12 | (ŪrdhvaBṛhatī) | #mahé vā́jāya śrávase dhíyaṃ dadhuḥ# |

| 10.35.5 | 6-7-8 | of | 12 | (Jagatī) | #bhadrā́ no adyá śrávase vy u\cchata# {205|206} |

| 10.59.2 | 9-10-11 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #kárāmahe sú purudhá śrávāṃsi# |

| 10.61.24 | 6-7-8 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #vípraś cāsi śrávasaś ca sātáu# |

| 10.116.6 | 9-10-11 | of | 11 | (Triṣṭubh) | #vy àryá indra tanuhi śrávāṃsi# {206|207} |

Table 3. Rig-Vedic Occurrence-Frequency of śrávas (Nominative/Accusative Singular) in the Various Positions (Horizontal Axis) of the Various Meters (Vertical Axis)

| 1-2 | 2-3 | 3-4 | 4-5 | 5-6 | 6-7 | 7-8 | 8-9 | 9-10 | 10-11 | 11-12 | |

| 8-syllabic | 8x | 0x | 3x | 0x | 11x | 0x | 21x | ||||

| 12-syllabic | 4x | 0x | 3x | 0x | 0x | 0x | 0x | 0x | 2x | 0x | 7x |

| 11-syllabic | 4x | 0x | 10x | 0x | 3x | 5x | 0x | 0x | 3x | * |

* ix, in an irregular verse.

Table 4. Rig-Vedic Occurrence-Frequency of śrávas in All Cases and Numbers Other Than the Nominative/Accusative Singular

| 1-2-3 | 2-3-4 | 3-4-5 | 4-5-6 | 5-6-7 | 6-7-8 | 7-8-9 | 8-9-10 | 9-10-11 | 10-11-12 | |

| 8-syllabic | 5x | 1x | 5x | 4x | 1x | 1x | ||||

| 12-syllabic | 0x | 0x | 1x | 0x | 2x | 6x | 0x | 0x | 1x | 0x |

| 11-syllabic | 2x | 0x | 3x | 0x | 10x | 6x | 0x | 0x | 8x | {207|208} |

Table 5. Rig-Vedic Occurrence-Frequency of śrávas in All Singular Cases Other Than the Nominative/Accusative

| 1-2-3 | 2-3-4 | 3-4-5 | 4-5-6 | 5-6-7 | 6-7-8 | 7-8-9 | 8-9-10 | 9-10-11 | 10-11-12 | |

| 8-syllabic | 3x | 0x | 0x | 4x | 0x | 0x | ||||

| 12-syllabic | 0x | 0x | 0x | 0x | 2x | 6x | 0x | 0x | 0x | 0x |

| 11-syllabic | 0x | 0x | 0x | 0x | 10x | 6x | 0x | 0x | 0x |

Table 6. Rig-Vedic Occurrence-Frequency of śrávas in All Plural Cases

| 1-2-3 | 2-3-4 | 3-4-5 | 4-5-6 | 5-6-7 | 6-7-8 | 7-8-9 | 8-9-10 | 9-10-11 | 10-11-12 | |

| 8-syllabic | 2x | 1x | 5x | 0x | 1x | 1x | ||||

| 12-syllabic | 0x | 0x | 1x | 0x | 0x | 0x | 0x | 0x | 1x | 0x |

| 11-syllabic | 2x | 0x | 3x | 0x | 0x | 0x | 0x | 0x | 8x | {208|209} |

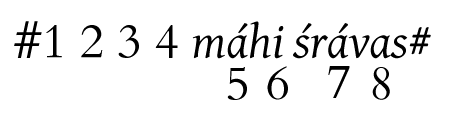

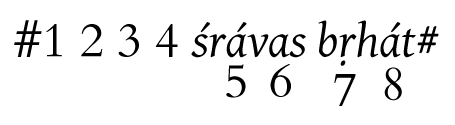

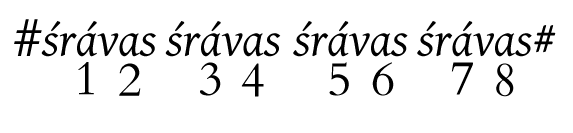

The point of departure in this extended survey of śrávas-collocations will be the proposed diachronic 4 + 4 + 4 segmentation of dodecasyllabic verses. We have already seen how the distribution of máhi śrávas adheres to such a segmentation, and now further evidence emerges from the list in Table 1. For example, just as máhi śrávas may occupy 9 10 11 12 of 12 as well as 5 6 7 8 of 8, so also śráva(s) bṛhát: RV 1.9.7/8, 1.44.2, 5.86.6, 8.9.17, 8.65.9, 9.44.6, 9.98.8 (5 6 7 8 of 8); 9.83.5, 9.86.40 (9 10 11 12 of 12); or again, just as máhi śrávas alternatively occupies 1 2 3 4 of 8, so also śráva(s) bṛhát: 8.31.7. To sum up, let us map out the positions:

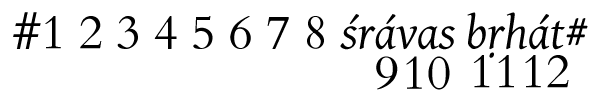

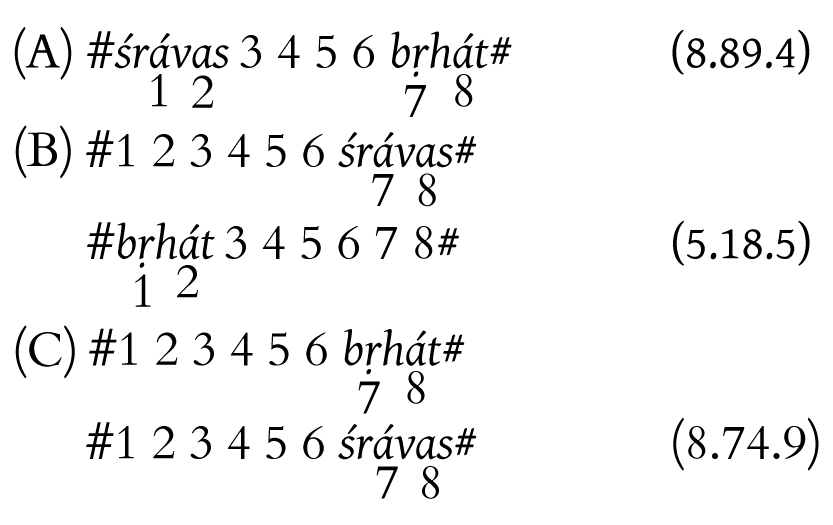

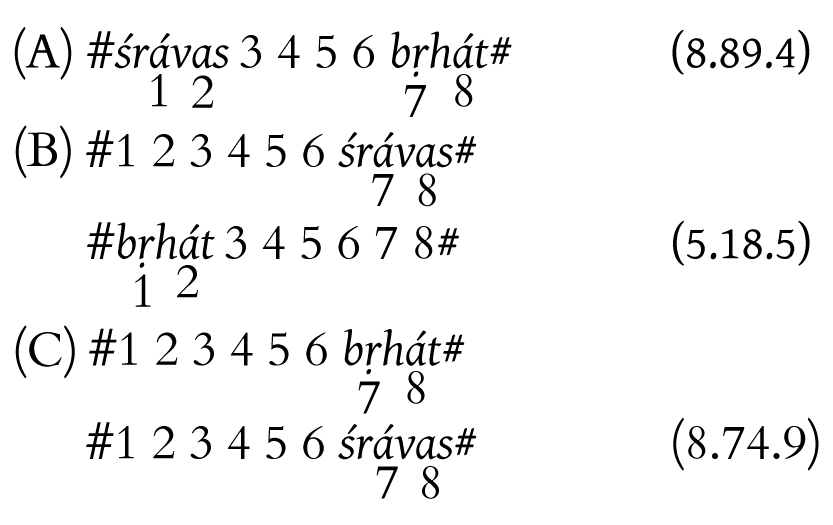

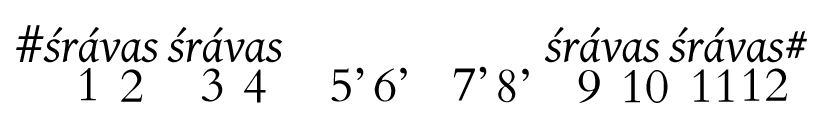

The positions of the phrase śráva(s) bṛhát follow definite patterns not only in contiguity but also in tmesis, that is, when śrávas and bṛhát are separated by intervening (A) words, {209|210} (B) verse-boundaries, or (C) both:

Type A shows both śrávas and bṛhát occupying slots which they also have when they are in contiguity, 1 2 (3 4) and (5 6) 7 8 respectively. In type C, however, only bṛhát occupies the slots which it also has in contiguity with śrávas, namely (5 6) 7 8, while śrávas itself occurs in a slot independent of its position in contiguity with bṛhát, namely 7 8. To put it another way: in terms of the ensemble śráva(s) bṛhát, the tmesis of type C has resulted in a slot-switch for śrávas but not for its epithet, bṛhát. Such coexistence of noun + epithet combinations in both contiguity and tmesis offers additional incentive for reconstructing śráva(s) ákṣitam in contiguity, alongside the actually attested Rig- Vedic śrávas … ákṣitam in tmesis; the epithet ákṣitam remains at 6 7 8 in both the reconstructed and the actual instance. [6] {210|211} As for Type B, neither śrávas nor bṛhát occupies the slots which they have when they are in contiguity. On the other hand, slot 5 6 before śrávas is occupied by máhi in the only representative of type B (5.18.5), and this fact may be a key to the explanation: I propose that the phrase máhi śrávas has taken precedence over śráva(s) bṛhát, and a conflation of the two phrases results in positional rearrangement of the latter in favor of the former.

Type A shows both śrávas and bṛhát occupying slots which they also have when they are in contiguity, 1 2 (3 4) and (5 6) 7 8 respectively. In type C, however, only bṛhát occupies the slots which it also has in contiguity with śrávas, namely (5 6) 7 8, while śrávas itself occurs in a slot independent of its position in contiguity with bṛhát, namely 7 8. To put it another way: in terms of the ensemble śráva(s) bṛhát, the tmesis of type C has resulted in a slot-switch for śrávas but not for its epithet, bṛhát. Such coexistence of noun + epithet combinations in both contiguity and tmesis offers additional incentive for reconstructing śráva(s) ákṣitam in contiguity, alongside the actually attested Rig- Vedic śrávas … ákṣitam in tmesis; the epithet ákṣitam remains at 6 7 8 in both the reconstructed and the actual instance. [6] {210|211} As for Type B, neither śrávas nor bṛhát occupies the slots which they have when they are in contiguity. On the other hand, slot 5 6 before śrávas is occupied by máhi in the only representative of type B (5.18.5), and this fact may be a key to the explanation: I propose that the phrase máhi śrávas has taken precedence over śráva(s) bṛhát, and a conflation of the two phrases results in positional rearrangement of the latter in favor of the former.

Indirect typological parallels are available from Greek Epic: for example, conflation of the common verse-final phrase πιcτὸν ἑταῖρον# and ἐcθλὸν ἑταῖρον# likewise results in positional rearrangement of one in favor of the other. What results is πιcτὸν ἑταῖρον#ἐcθλὸν (Ρ 589-590). Consider also this other verse-final example: χαλκοβατὲc δῶ# (Α 426, etc.) plus ὑψερεφὲc δῶ# (κ 111, etc.) result in χαλκοβατὲc δῶ#ὑψερεφέc (ν 4-5). In these instances, the phrase subjected to rearrangement is probably the older of the two, as we can see from such obvious innovations as χάλκεα τεύχεα#κᾶλά (Χ 322-323); here the monosyllabic scansion of etymologically disyllabic εα in τεύχεα clearly indicates the recent date of the formula χάλκεα τεύχεα#, as contrasted with the frequent archaic formula τεύχεα κᾶλά#. These two phrases are especially suitable for comparison with Rig-Vedic máhi śrávas and śráva(s) bṛhát because the word-order also matches: epithet-plus-noun vs. noun-plus-epithet respectively. {211|212}

Likewise in máhi śrávas#bṛhát, the rearranged constituent śráva(s) bṛhát may be the earlier phrase, since it is not even attested with a declension in the Rig-Veda, unlike máhi śrávas (with genitive śrávasas mahás, dative śrávase mahé). Lack of declension for a nominal verse-element implies one of two chronological extremes. It entered the traditional poetic repertory either too early or too late for the process of declension to take hold. In the first alternative situation, the given form is too ossified in usage to be capable of synchronic declensional extension, while in the second, the synchronic mechanisms of phraseology/meter can no longer accommodate new declensional forms. The first alternative seems to fit śráva(s) bṛhát, since the Rig-Vedic adjective bṛhát is freely attested as qualifier, in oblique cases, of neuter substantives other than śrávas, and no resulting phraseological or metrical difficulties are apparent. As for the Greek Epic, the cognate of śrávas shows case-restriction by archaic usage, even without epithet-conditioning. Of the 70-odd Homeric attestations of κλέοc, only 4 are not in the nominative/accusative singular, and even these exceptions are merely pluralized (κλέα) but not declined.

And yet, although case-extension may be an innovation in relation to case-restriction, this is not to say that the Rig-Vedic occurrences of trisyllabic case-forms śrávasas/śrávase/śrávasi/śrávasā are not crucial in indicating archaic {212|213} positions from which disyllabic śrávas has been eliminated. In matters of poetic language, I would postulate that once archaism A undergoes innovation B, this innovation B may resist a further innovation C more effectively than archaism A. In fact, I hope to show that declined forms of śrávas- (cf. B) resist metrical leveling (cf. C) more effectively than undeclined śrávas (cf. A). [7] But the immediate argument remains simply that the formula śráva(s) bṛhát is more archaic than máhi śrávas, since it survives without a declension.

In the phrase śráva(s) bṛhát, the epithet is actually less flexible in position than the noun; further, the pattern máhi śrávas#bṛhát suggests that shifting of the epithet happens only when another noun + epithet combination interferes by superimposition rather than apposition.

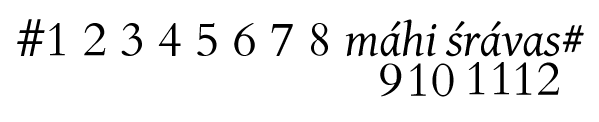

The positional shifts of śrávas follow a predictable pattern even if the reinforcing epithets are left out of consideration. Thus in 8-syllable and 12-syllable verses of the Rig-Veda, śrávas always begins on an odd syllable and never on an even syllable; in other words, it is absent from slots 2 3, 4 5, 6 7, 8 9, 10 11. [8] I find it especially remarkable that śrávas is absent from 2 3 and 4 5, in view of the inherited flexibility in the rhythm of the verse-opening. We may achieve a more precise {213|214} understanding of the distributional patterns by collecting all attested Rig-Vedic positions of śrávas in 8-syllable and 12-syllable verses and placing them side by side. One result is that the opening and closing of both verses would then be covered over phraseologically:

= ⏑ – ⏑ – ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓

= ⏑ – ⏑ – ⏓ ⏓ ⏓ ⏓ ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓

The appended scansions are imaginary in that they presuppose a sequence consisting of the same word, but they are real in showing the metrical constraints to which the word adheres. The short quantity of elements 1 3 5 7 9 11 is not only the natural quantity of the first syllable in śrávas; it also happens to be the optional (in the opening) or regular (in the closing) metrical quantity of these elements in attested Indic octosyllables and dodecasyllables. As for the quantity of elements 2 4 6 8 10, we cannot simply assume the long quantities as they are represented in the imaginary scansion; length in the second syllable of śrávas is possible only if the following word begins with a consonant.

= ⏑ – ⏑ – ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓

= ⏑ – ⏑ – ⏓ ⏓ ⏓ ⏓ ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓

Here we must turn to the actual evidence of the text: among 87 Rig-Vedic attestations of śrávas in the nominative/accusative singular, {214|215} all but 12 are in preconsonantal position. Of these 12 exceptional instances showing prevocalic śrávas (hence ⏑ ⏑, vs. preconsonantal ⏑ –), 11 are in Triṣṭubh verse. Only one is in an octosyllabic verse, and even here śrávas is in the opening, not the closing: śráva(s) ámṛtyu in slots 1 2 3 4 5, RV 6.48.12. [9] Likewise, among the 11 instances of prevocalic śrávas in Triṣṭubh, not a single one is in the closing:

1 2: 1x, 3 4: 2x, 5 6: 3x, 6 7: 5x

In fact, no instance of preconsonantal śrávas is attested for slots 5 6 and 6 7 of hendecasyllables; they are reserved for prevocalic śrávas. [10] But the point at hand remains simply that in Rig-Vedic octosyllables and dodecasyllables, śrávas is regularly in preconsonantal position, with only one exception; and there is no attestation of slot-overlap, by contrast to the 5 6 vs. 6 7 overlap in hendecasyllables. Hence the validity of the scansions ⏑ – ⏑ – ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓ and ⏑ – ⏑ – ⏓ ⏓ ⏓ ⏓ ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓: they have been constructed solely from the positional contexts of śrávas.Since such a pattern as ⏑ – ⏑ – ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓ happens to coincide with one of the ultimate stages in Rig-Vedic metrical fixation, [11] we may begin to suspect that traditional phraseology such as the śrávas- distribution is not only rigid by inheritance but is made even more rigid by {215|216} current trends in metrical evolution. And yet, the central theme of this entire investigation has been that phraseology is the diachronic mold of meters, not vice versa. The paradox here may perhaps be resolved by simultaneous application of diachronic and synchronic perspectives: I repeat my hypothesis that newly-evolved laws of meter may obliterate aspects of the selfsame traditional phraseology which engendered them, if these aspects no longer match the meter. [12] For a specific explanation, we need to examine further the following factors in the distribution of śrávas: (1) stricture vs. license in slot-overlap; (2) preconsonantal vs. prevocalic word-end; (3) word-start on odd vs. even syllable.

The horizontal axis of Table 3 (p. 207) is a useful point of departure. An ‘0x’ indicates that there is no overlap, while the absence of this sign ‘0x’ indicates that there is one (as between 5 6 and 6 7 in hendecasyllabic verses). When we set these instances of ‘0x’ into proportions with occurrence-frequencies of slots actually occupied by śrávas, these proportions reveal the same kind of patterns already discovered from epithet-combinations with śrávas. For example, just as the distribution of máhi śrávas and śráva(s) bṛhát suggests structural affinity between the 5 6 7 8 of octosyllables and the 9 10 11 12 of dodecasyllables, so also this proportion: {216|217}

0x of 6 7 is to 21x of 7 8 in octosyllables

as

0x of 10 11 is to 7x of 11 12 in dodecasyllables

Such statistical parallelism, then, illustrates the kindred dynamics of closings in dimeter and trimeter.Other such parallelisms are apparent from similar comparisons of coordinates 4 5, 5 6, 6 7, 7 8 in octosyllables vs. 8 9, 9 10, 10 11, 11 12 in dodecasyllables. But there are even more interesting parallelisms elsewhere, as in the distribution of trisyllabic declensional forms of śrávas- in dodecasyllables and hendecasyllables. Because of trisyllabic śrávas (C)V(C)-, two consecutive occurrences of ‘0x’ are required here for non-overlap:

6x of 6 7 8 is to 0x of 7 8 9 plus 8 9 10 in dodecasyllables

as

6x of 6 7 8 is to 0x of 7 8 9 plus 8 9 10 in hendecasyllables

This dodecasyllabic/hendecasyllabic statistical parallelism in occurrence and non-overlap is matched by parallelism in occurrence and overlap. Again, we see from Table 4 (p. 207):

2x of 5 6 7 overlaps with 1x of 3 4 5 in dodecasyllables

as {217|218}

10x of 5 6 7 overlaps with 3x of 3 4 5 in hendecasyllables;

also:

2x of 5 6 7 overlaps with 6x of 6 7 8 in dodecasyllables

as

10x of 5 6 7 overlaps with 6x of 6 7 8 in hendecasyllables.

These close statistical parallelisms in dodeca-syllables and hendecasyllables corroborate a theory of metrical derivation: that the latter verse-type equals the former minus the last syllable, in other words, that the latter equals the former by catalexis. [13] The overlap last to be mentioned, that of 5 6 7/6 7 8, is even more significant: this trisyllabic overlap matches the disyllabic overlap of 5 6/6 7 in hendecasyllables. [14] Besides the overlap, there are also other factors involved in this correspondence between 5 6/6 7 and 5 6 7/6 7 8. Every instance of śrávas in hendecasyllabic slots 5 6 and 6 7 is in prevocalic position, whence the scansion ⏑ ⏑. [15] As for the declensional forms of śrávas which occupy slots 5 6 7 and 6 7 8, they are all in the singular: śrávasas, śrávase, śrávasi, śrávasā. Thus the stem śrávas- is always {218|219} immediately followed by a vowel, whence the scansion ⏑ ⏑ ⏓. By contrast, the plural attestations of śrávas, namely śrávāṃsi, śrávobhis, śrávassu, are all to be scanned as ⏑ – ⏓. Thus the division of Table 4 (p. 207) into separate Tables 5 and 6 (p. 208) is based on not only grammar but also meter, since these two tables represent the separation of trisyllabic śrávas- forms into categories of ⏑ ⏑ ⏓ and ⏑ – ⏓ respectively. From Table 5 (p. 208), presently under consideration, the correspondence of 5 6 7/6 7 8 between dodecasyllables and hendecasyllables emerges even more strikingly than from Table 4 (p. 207), since it now becomes clear that this slot-overlap is correlated exclusively with the scansion ⏑ ⏑ ⏓ in trisyllabic forms of śrávas-. And since trisyllabic forms of śrávas-, scanned ⏑ ⏑ ⏓, correspond to disyllabic śrávas in prevocalic position, the matching of 5 6 7/6 7 8 in Table 5 (p. 208) with 5 6/6 7 in Table 3 (p. 207) becomes all the more significant. In one dimension, there is the slot-parallelism of dodecasyllables with their catalectic variant, the hendecasyllables; in the other dimension, there is the rhythm-parallelism of śrávasas/śrávase/śrávasā with prevocalic śrávas. As for the absence of prevocalic śrávas from slots 5 6 and 6 7 of dodecasyllables, this must be contrasted with the presence of śrávasas/śrávase/śrávasi/śrávasA in slots 5 6 7 and 6 7 8 of the same dodecasyllables. The questions raised by such a contrast must be postponed until we {219|220} finish with the last of the three factors operative in the distribution of śrávas.

Aside from the five instances where it starts on 6 7 of hendecasyllables, śrávas regularly starts on odd syllables. I propose that a diachronic segmentation 4 + 4 + 4 in dodecasyllabic verse and, to extend the claim, 4 + 4 + 3 in the hendecasyllabic, must have been a factor. [16] Starting on odd syllables entails, in turn, a further constraint on the distribution of śrávas. Since a basic trend of Vedic meter is the elimination of two-short sequences, [17] we may expect the short first syllable of śrávas to predicate length in the second, and length is achieved by regular preconsonantal positioning. For the moment, I have described these positioning patterns without making a commitment on whether the ultimate cause is meter or phraseology.

We have yet to examine the five instances of śrávas starting on an even syllable, in slot 6 7. The position of śrávas in slot 6 7 of hendecasyllables has already been described as anomalous in comparison with other positions, since (1) it is exclusively prevocalic and (2) it overlaps with 5 6. The positions of śrávasas/śrávase/śrávasi/śrávasā in slot 6 7 8 of hendecasyllables and dodecasyllables is likewise anomalous, since these forms have no other trimeter positions except in the overlapping slot 5 6 7. [18] There is, {220|221} moreover, a third shared anomaly: the word-start is on an even syllable. The very consistency of these three anomalies on the statistical level suggests that they are traditional. Notice that the occupation of the slot 6 7 (8) means that the caesura comes after the fifth syllable. [19] By contrast, occupation of the slot 5 6 (7) implies a trimeter caesura after the fourth syllable. In sum, the variation of śrávas- between slots 5 6 (7) and 6 7 (8) in trimeter corresponds to the traditional variation of caesura between …4|| and …5|| respectively. The word śrávas is regularly prevented from starting on an even syllable unless the trimeter segmentation is 5 + 7 (5 + 6) instead of 4 + 8 (4 + 7). In other words, there is now further evidence for the proposition that trimeter segmentation is somehow correlated with whether śrávas starts on an odd or even syllable.

I have noted that all instances of śrávas starting on an odd syllable are preconsonantal, for which reason the regular scansion is ⏑ –, as opposed to prevocalic ⏑ ⏑. The one attestation where śrávas has resisted this basic metrical trend is in the archaic phrase śráva(s) ámṛtyu, [20] in the metrically archaic hymn RV 6.48. [21] Even śráva(s) ámṛtyu has survived only in the opening, not in the metrically rigid closing. We seem to {221|222} have here an instance where meter has obliterated traditional phraseology from the most conservative part of the verse, the closing. [22] To reword the original hypothesis: whereas ever-increasing fixation of meter in the closing increasingly restricts phrase-improvisation and thereby favors the preservation of some traditional phrases, other traditional phrases may be obliterated by the same process. And even in the opening, there is but one residual representative of śrávas in a less restricted metrical pattern.

Significantly, however, this pattern ⏑ ⏑ for slots 1 2 is effectively preserved in trisyllabic declensional forms of śrávas- in slots 1 2 3; Table 5 (p. 208) shows three such attestations. In other words, the pattern ⏑ ⏑ of śrávas-, which can be metrically obliterated in its disyllabic forms, cannot be obliterated in its trisyllabic forms. Thus Table 5 may reveal distributional archaisms that are not present in Table 3 (p. 207). One such archaism is the attestation (6 times) of trisyllabic śrávas- in slots 6 7 8 of dodecasyllables (a pattern acquired perhaps from hendecasyllables), vs. the absence of disyllabic śrávas in slots 6 7 of dodecasyllables.

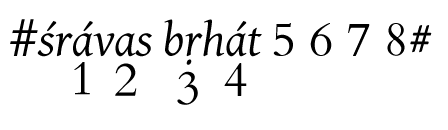

Another such archaism is the attestation (4x) of trisyllabic śrávas- in slots 4 5 (6) of octosyllables, vs. the absence of disyllabic śrávas in slots 4 5: {222|223}

RV 7.16.10 #kā́mena śrávaso mahás#

8.70.9 #úd indra śrávase mahé#

8.74.9 #úpopa śrávasi śrávas#

9.62.22 #gṛṇānā́ḥ śrávase mahé#

The scansion ⏑ ⏑ for 4 5 in attested śrávasas, śrávase, and śrávasi is crucial for my argument because it coincides with the ⏑ ⏑ of 4 5 in the reconstructed śráva(s) ákṣitam#. Also crucial is the fact that śrávasa(s) mahás# and śrávase mahé# in octosyllables are in effect declensional variants of the phrase máhi śrávas#, likewise in octosyllables. Here, then, is collocational evidence for the interchange of śrávas- between slots 4 5 and 7 8. As for RV 8.74.9, with #úpopa śrávasi śrávas#, it is a matter not just of interchange but of actual contiguity of śrávas- in slots 4 5 and 7 8. Such interchange between 4 5 and 7 8 is exactly what has been posited for śráva(s) ákṣitam# vs. ákṣiti śrávas#. [23] That śráva(s) ákṣitam# is no longer attested in contiguity (but only in tmesis: śrávas … ákṣitam#) can be blamed on two main factors: (1) the synchronically irregular metrical pattern of the phrase śráva(s) ákṣitam# = ⏑ ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓, with two shorts in śrávas; [24] (2) the availability of a metrically regular substitute, ákṣiti śrávas# = – ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓. [25] 8.70.9 #úd indra śrávase mahé#

8.74.9 #úpopa śrávasi śrávas#

9.62.22 #gṛṇānā́ḥ śrávase mahé#

There are important implications in the {223|224} meter of the phrases just surveyed—

śrávasa(s) mahás#,

śrávase mahé#,

śrávasi śrávas#,

śráva(s) ákṣitam#—

all scanned ⏑ ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓. The catalectic variant of such a metrical sequence, that is, ⏑ ⏑ – ⏓, is the important paroemiac cadence of Greek and Slavic meter, a rhythmical pattern which can be reconstructed as an Indo-European inheritance. [26] śrávase mahé#,

śrávasi śrávas#,

śráva(s) ákṣitam#—

There are also traces of the pattern ⏑ ⏑ – ⏓ in Rig-Vedic hendecasyllables, [27] just as there are traces of ⏑ ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓ in dodecasyllables. Nevertheless, the regular pattern is – ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓ in the Rig-Vedic dodecasyllable, and – ⏑ – ⏓ in its catalectic variant, the hendecasyllable. Also, slot 8 of – ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓ (= 8 9 10 11 12) or of – ⏑ – ⏓ (= 8 9 10 11) belongs diachronically to the middle portion of an original 4 + 4 + 4 or 4 + 4 + 3 segmentation; [28] in other words, slot 8 is not in the closing portion, from the genetic standpoint of my reconstruction. The problem, then, is how to reconcile the comparative metrical evidence and the internal phraseological evidence for a unit ⏑ ⏑ –⏑ ⏓ with the internal metrical and phraseological evidence for an original 4 + 4 + 4 segmentation of dodecasyllabic verse.

The key to a solution is this: although {224|225} dodecasyllables consist of a 4 + 4 + 4 segmentation in terms of my reconstruction, the 3 units of 4 syllables are not on the same level as units. On one hand, the dodecasyllable originates from the 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 of octosyllables, plus another 5 6 7 8 = 9 10 11 12. In other words, the last 4 syllables of an 8-syllable verse are split off and added to another 8-syllable verse. This phenomenon is still synchronically visible in Uṣṇih dodecasyllables and, to a lesser extent, even in Jagatī dodecasyllables. [29] On the other hand, the dodecasyllable also consists diachronically of the 1 2 3 4 of octosyllables, plus another 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 = 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12. An obvious reflex of this partition is the regular caesura pattern …4|| in trimeter.

Unlike the relatively more recent 5 + 5 segmentation of dodecasyllables, [30] the 4 + 4 segmentation of octosyllables arises because the constituents are perpendicular, not parallel, in structure: the rhythm is flexible vs. rigid in the opening 1 2 3 4 vs. closing 5 6 7 8; the dynamic tension extends into specifics too. For example, if the closing tends toward trochaic – ⏑ – ⏓, then the opening will tend toward iambic ⏑ – ⏑ –. [31] The dodecasyllable, in a sense, is just an elaboration on this non-parallelism in the octosyllable. The 4 + 4 + 4 segmentation is a conflation of opening/closing/closing and {225|226} opening/opening/closing, in terms of the octosyllable. Another way to put it: the dodecasyllable is diachronically a conflation of 4 + 8 and 8 + 4 segments rather than a simple succession of 4 + 4 + 4 segments.

By contrast, the 4 + 4 segmentation of octosyllables is an innovation. The most obvious sign is a negative reality, to wit, that there has been no regularization of any caesura pattern …4|| as in dodecasyllables. There is no such regularization despite the archaic phrase patterns that could set a precedent for …4||. I would suggest, however, that traditional phraseology merely offers opportunities for various developments in traditional meter, and that these opportunities are diachronically optional. A diachronic trend may become a synchronic constant, but not inevitably. In other words, I propose that the caesura is a synchronic metrical constant generated by a diachronic phraseological trend. I propose that in the case of Indic octosyllables, such a metrical constant never became generalized despite the diachronic opportunities available.

Another indication that the Indic 4-syllable unit is an innovation comes from statistical evidence. The closing of dodecasyllables is rhythmically stricter than that of octosyllables. Even the octosyllables which alternate with dodecasyllables in Uṣṇih, Satobṛhatī, and so on, have a stricter iambic closing than the octosyllables which do not alternate with dodecasyllables, {226|227} in Anuṣṭubh and Gāyatrī. [32] Lastly, of the 150-odd attestations of Rig-Vedic verses consisting of 4 syllables only, nearly all have the strict iambic rhythm ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓. This one factor was enough to convince Arnold that the 4-syllable unit is derived from the second half of octosyllables, [33] not vice versa.

In sum, the Rig-Vedic evidence does not negate the reconstruction of a phraseological unit śráva(s) ákṣitam and of an accompanying metrical unit ⏑ ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓ for slots 4 5 6 7 8 of octosyllables. Rather, the available evidence suggests that these units are so archaic that they predate the 4 + 4 segmentation of the Indic octosyllable. The pattern ⏑ ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓ is even found in dodecasyllabic closings. In such cases, I suppose that the phraseology of the given dodecasyllable originated from a pattern shaped 1 2 3 4 + 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 (that is, opening + opening + closing), not the alternative 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 + 5 6 7 8 (that is, opening + closing + closing). The same etymology, if we may call it that, holds for the catalectic variant in hendecasyllables, ⏑ ⏑ – ⏓ (vs. normal – ⏑ – ⏓). Of course, the rhythmical pattern ⏑ ⏑ – ⏓ is the same as the Indo-European paroemiac closing. [34] The phrase unit śráva(s) ákṣitam, however, would have originated in the octosyllable and remained appropriate only to the {227|228} octosyllable, since its metrical pattern ⏑ ⏑ –⏑ ⏓ becomes incongruous with the Indic pattern – ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓, generalized by dodecasyllables. Instances of ⏑ ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓ are only sporadic.

Even in octosyllables there is an increasing predominance of long over short in syllable 5 of 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8. In other words, – ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓ ousts ⏑ ⏑ – ⏑ ⏓. This factor, along with an emergence of 4 + 4 segmentation, causes the loss of śráva(s) ákṣitam in contiguity at the closing of the octosyllable. Also, there is obsolescence of śrávas from syllables 4 5. But trisyllabic śrávasas/śrávase/śrávasi in syllables 4 5 6 were more resistent to obsolescence because there was no substitute readily available. [35] As for the occurrence of ákṣiti śrávas in place of śráva(s) ákṣitam at 4 5 6 7 8, the former phrase actually conforms to the 4 + 4 segmentation which is emergent in octosyllables. The privative particle a- counted as a separate lexical element in early Indic versification. [36] Thus the occupation of syllable 4 by a- in ákṣiti śrávas# would have been possible even if the Indic octosyllable had generalized a caesura to accompany the evolving 4 + 4 segmentation.

Footnotes

[ back ] 1. See pp. 177-181.

[ back ] 2. Cf. Oldenberg 1888:96n3.

[ back ] 3. Arnold 1905:14; also, cf. pp. 177-181 above.

[ back ] 4. For elaboration of the thematic axis opposing gods and men, see Nagy, “ἀνήρ and ἄνθρωποc,” forthcoming.

[ back ] 5. Arnold 1905:162; also, cf. pp. 171-177 above.

[ back ] 6. Cf. pp. 110-114.

[ back ] 7. Cf. especially pp. 221-223.

[ back ] 8. Table 3, p. 207.

[ back ] 9. Cf. Table 1, pp. 197-202.

[ back ] 10. Cf. Table 3, p. 207.

[ back ] 11. Cf. pp. 35f.

[ back ] 12. Pp. 196, 221f.

[ back ] 13. Pp. 166f, 180f.

[ back ] 14. Cf. Table 3, p. 207.

[ back ] 15. Cf. pp. 213-215.

[ back ] 16. Cf. pp. 167-184, 195f.

[ back ] 17. Meillet 1923:46.

[ back ] 18. Table 5, p. 208.

[ back ] 19. For the metrical implications of caesura after 5 vs. 4, see again pp. 177-184.

[ back ] 20. Cf. pp. 161f.

[ back ] 21. Arnold 1905:304.

[ back ] 22. Cf. p. 196.

[ back ] 23. pp. 113f.

[ back ] 24. On the obsolescence of double-short sequences in Indic, see again Meillet 1923:46.

[ back ] 25. Cf. again pp. 113f.

[ back ] 26. Jakobson 1952:62-66.

[ back ] 27. Watkins 1963:210.

[ back ] 28. pp. 171-177.

[ back ] 29. Ibid.

[ back ] 30. pp. 177-184.

[ back ] 31. pp. 170f.

[ back ] 32. Arnold 1905:170.

[ back ] 33. Arnold 1905:162.

[ back ] 34. p. 224.

[ back ] 35. pp. 222f.

[ back ] 36. Arnold 1905:180.